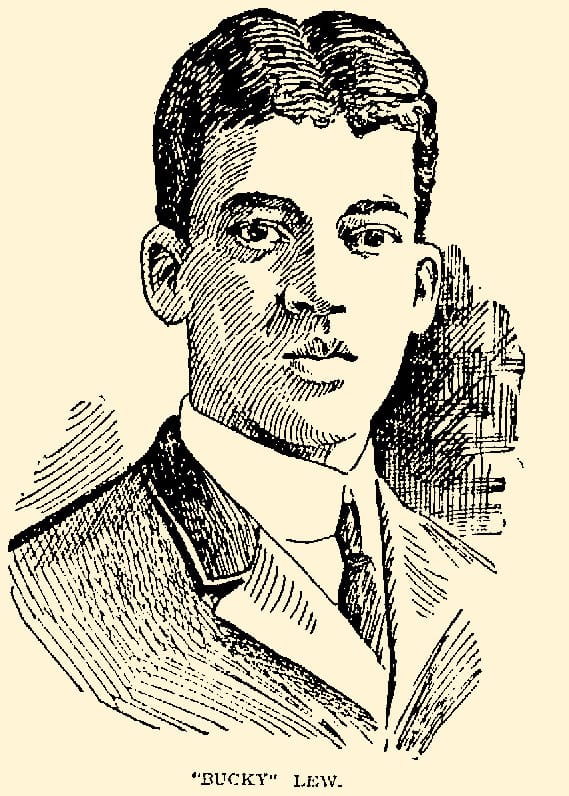

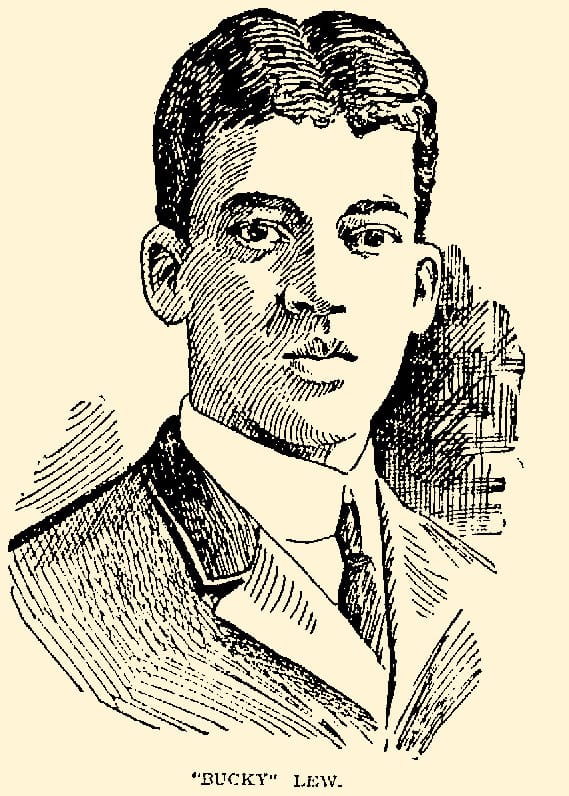

The original French Connection — from Bucky Lew to Jackie Robinson

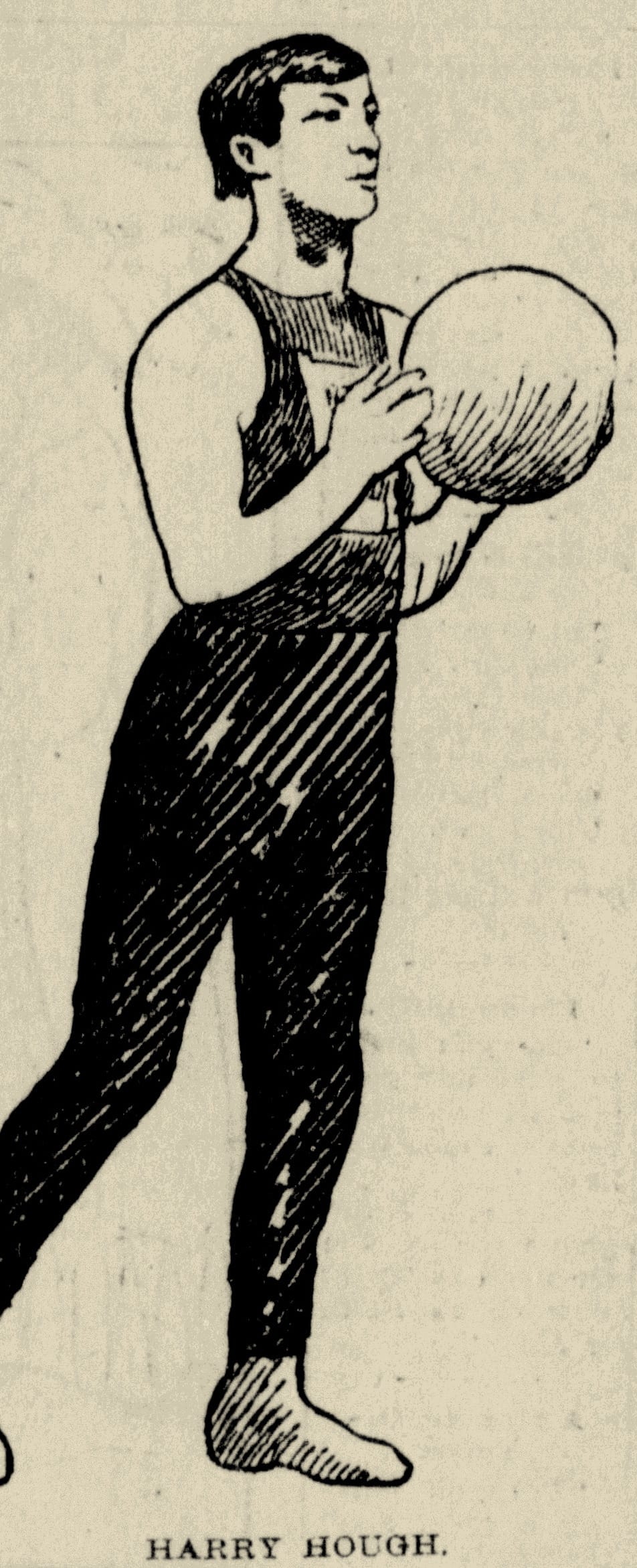

Bucky Lew, basketball’s first Black professional, first made a name for himself in Manchester in January of 1903 when he held the game’s best player, Harry Hough, to two points in their early-season matchup.

MANCHESTER, NH –Bucky Lew, basketball’s first Black professional, first made a name for himself in Manchester in January of 1903 when he held the game’s best player, Harry Hough, to [a net of] two points in their early-season matchup.

Hough averaged 16 points a game in what amounted to basketball’s dead ball era, when the best teams typically topped out at 30. He scored [only six points that night, while Lew almost matched him, scoring 4 himself].

Lew’s hometown paper, The Lowell Sun, reported that “Bucky Lew played Hough to perfection” in leading his team to the win.

It wouldn’t be the only time the pair made headlines together. The next year, after Lew moved from Lowell to Haverhill and Hough from Manchester to Natick, Hough refused to play against him.

Hough led his teammates in protest and they refused to engage in any basketball activities while Lew remained on the floor. The only time Hough moved was to dodge a basketball Lew’s teammate fired at his head.

While he claimed his stand was based on his Southern upbringing (questionable considering he was from Pennsylvania), knowledgeable observers suspected there was another reason.

According to the Evening Democrat of Waterbury, Connecticut, “Hough quit because he was afraid to measure his abilities with the colored boy… Bucky Lew is one of the best backfield players in the country.”

League leaders met in an emergency meeting following the game and sided with Lew. Natick was fined and threatened with expulsion if they did it again. Apparently the players were most concerned with the color green, because Hough and his teammates fell in line.

The two teams met again for the championship of the New England League later that year but Lew was unable to exact revenge. He suffered a dislocated shoulder after the first game and missed most of the series. With Lew in a compromised condition, Hough went off and led his team to the win.

The NEL folded after that but Lew continued to advance in a career that spanned 25 years. He went on to become the first Black coach, manager, head referee, and owner in the otherwise white leagues. He brought his barnstorming team throughout Massachusetts and New Hampshire year after year and was reportedly a crowd favorite. After he broke a leg in 1915, the Lowell Courier Citizen noted “Lew is known throughout New England among basketball fans as an exceptionally clean as well as skillful player” and that the injury took place “in Franklin, where he is a prime favorite.”

Lew’s legacy extends beyond that. He retired in 1926, and two decades later, the Dodgers placed three Black players in their minor league system—Don Newcombe and Roy Campanella in Nashua and Jackie Robinson in Montreal. Of course, the Dodgers moved Robinson up to the majors the next year.

The logical connection between Lew and Robinson is obvious. Lew compared himself to Robinson in perhaps the last interview he gave a reporter.

Speaking to Gerry Finn of the Springfield Union in 1958, Lew said: “All those things you read about Jackie Robinson, the abuse, the name-calling, extra effort to put him down… they’re all true. I got the same treatment and even worse…. I took the bumps, the elbows in the gut, knees here and everything else that went with it. But I gave it right back. It was rough but worth it. Once they knew I could take it, I had it made.”

Yet there appears to be an even more direct connection between the two. Lew started his pro career with a team in Lowell’s Pawtucketville neighborhood, also known as High Canada because of its large French-Canadian presence, and the Dodgers placed their first Black players in cities dominated by French-Canadians as well. The mill cities up and down the Merrimack River all had French-Canadian populations, as, obviously, does Montreal.

The Dodgers’ calls to the cities hosting their minor league teams were unsuccessful until they reached New Hampshire. In “Dem Little Bums: The Nashua Dodgers,” Steve Daly says Branch Rickey placed players in the city after a discussion with Fred Dobens, editor of the Nashua Telegraph, who assured him the players would be accepted and supported.

Why was the editor so sure? Dobens, who was born in 1905, and starred in high school basketball in the early 20s, undoubtedly grew up reading about Lew’s exploits and fan following.

Manchester hosted Newcombe and Campanella that first year with the Dodgers as home to a Yankees farm team. Only one potential racial incident occurred that season, when Sal Yvars tossed dirt at Campanella, the catcher, before an at-bat.

Yvars denied race had anything to do with it. He claimed he was upset because he was being thrown at. This seemed to be a chronic complaint of his. It was reportedly the reason he later took out the Dodgers’ first baseman while he was attempting to catch his infield pop-up, resulting in injury that hastened Walter Alston’s retirement as a player and move to full-time manager.

At any rate, one Franco-American connection is clear. If my grandfather Armias hadn’t left Quebec for New England in the 1920s, and settled in Pawtucketville as a neighbor to the Lews, I may never have heard of the man nor developed the interest in his accomplishments that inspired me to write his only book-length biography.

Chris Boucher is the author of “The Original Bucky Lew: Basketball’s First Black Professional.” He’ll be sharing stories and pics from Lew’s career at the Manchester City Library Sept. 26 at 7 p.m. (the date was rescheduled from July).