The milkman of human kindness

I came to Morocco to find a desert. Instead, I found an overflowing spring of humanity. In particular, I met Younes Krimane. Let me explain.

I came to Morocco to find a desert. Instead, I found an overflowing spring of humanity. In particular, I met Younes Krimane. Let me explain.

Yesterday I landed at Marrakesh Menara Airport. After about 20 hours stuck inside various metal tubes—bus, train, plane—I was disoriented, hungry and exhausted. Those who know me would argue the first of those is my regular condition, but I’ll ignore them for now. I picked up my rental car, a tiny Peugeot with all directions written in French, one of the many languages I don’t speak.

Full disclosure: English is the only language I have. At one point I was reasonably fluent in German but that’s long gone, and I was proud of my mastery of Koine Greek in seminary, although translating the Gospel doesn’t have any connection to carrying on even a simple conversation. As for Arabic, Morocco’s official language, I have memorized probably 30 phrases, so I can ask for directions, then not understand a word I’ve heard.

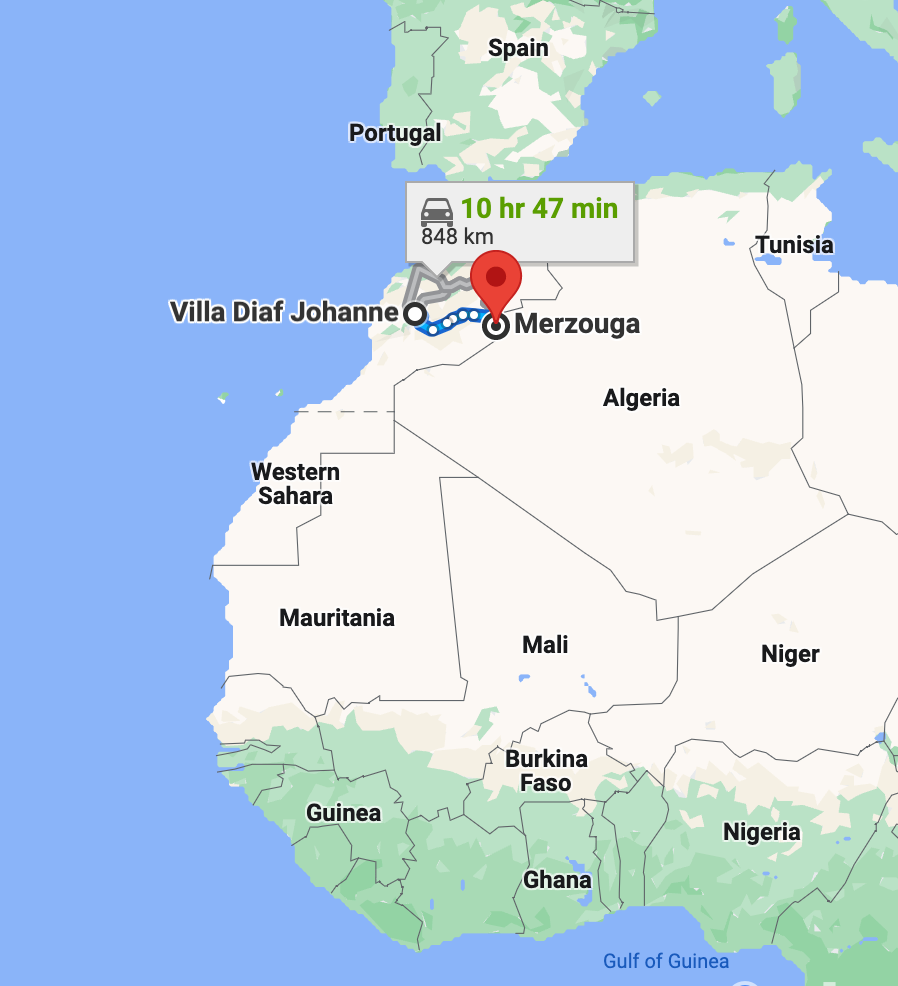

Leaving the airport, I relied on Google Maps to get me to the villa where I was spending my first night. This worked fine getting me eastward out of Marrakesh, despite the gnat-like presence of bicycles, motorcycles and horse-drawn carts. After 45 minutes, I turned off the highway, with two kilometers to Villa Diaf Johanne. I drove slowly with an irrigation ditch on my right-hand side and beautiful greenery all around me. Sure enough at two kilometers, although I saw nothing like a villa, Google Maps told me I had arrived at my destination—if I took a right turn. Into a ditch. Up to this point, I’d obeyed my technological masters, but even I wasn’t going to fall for this trick. Had I learned nothing from Michael Scott on “The Office”?

Seeing a bridge across the ditch a few hundred meters ahead, I drove on and crossed it, continuing to drive down the dirt road, passing other ditches and some kids resting in the shade until I realized there was no signage or indication of any lodging of any kind. Turning around, I thought I’d use my sub-pidgin Arabic to get directions.

When I got to the kids, they had been joined by a couple of women. I asked about Villa Johanne. Kindly, the women spoke to me in French. I stared. Then Spanish. I gawked. Then a flood of Arabic. In response I may have asked them for coffee or if the water was safe to drink. It’s a blur. Finally, the women offered to get in the car and show me the way. What kind people!

I turned the Peugeot around, put it in first gear and focused on the women in the back seat and their hand signals of direction. This focus was necessary, of course, but ill-advised. Creeping forward, I drove one of the wheels into a ditch. The car wasn’t damaged, but we were stuck. This is where my new friend, Younes Krimane, comes into the story out of nowhere. Really. He just appeared.

Being an old man, I am a terrible judge of peoples’ ages. Everyone except me looks young. I’ll guess Younes was in his 20s, wearing a T-shirt and shorts. Sizing up the situation, he got to work. The kids, the women and I stood back and let him do his magic. Within two minutes, he’d jacked up the car a few inches, driven forward and saved the day.

Although I like to see myself as non-transactional—which is to say not a person who feels every situation requires a quid pro quo—I am an American, so I reached into my wallet and pulled out some money for Younes. The amount was what I would offer anyone who had saved my day, my trip, my vacation—about $60. Younes demurred. Younes refused. Despite the pleas of the women—Younes’ mother and a friend? Neighbors? Strangers?–Younes shook his head. Finally, he took the money from me, only to put it back in my shirt pocket. The only thing Younes wanted was my contact information. Really. I gave him my business card and we shook hands.

The women climbed back into the car. They giggled and talked in the back seat as we drove the kilometer or so to Villa Diaf Johanne. I handed the money to one of them, trusting she would find a way to give it to Younes.

I write these words Friday morning from beside the pool pictured above. After breakfast, I’ll start my drive to Merzouga, the desert town where I’ll stay for at least a week. While I’ll need to drink lots of water, of course, I’ll also be strengthened by Younes Krimane, the milkman of human kindness.