Plaque in place on Elm Street honoring Samantha Plantin, city’s first Black female landowner

If anyone deserves a plaque on Elm Street for a life well-lived it’s Samantha Plantin who broke the city’s color, gender and economic barriers when she became the first Black female landowner in Manchester in the 1800s.

MANCHESTER, NH – If anyone deserves a plaque on Elm Street for a life well-lived it’s Samantha Plantin who broke the city’s color, gender and economic barriers when she became the first Black female landowner in Manchester in the 1800s.

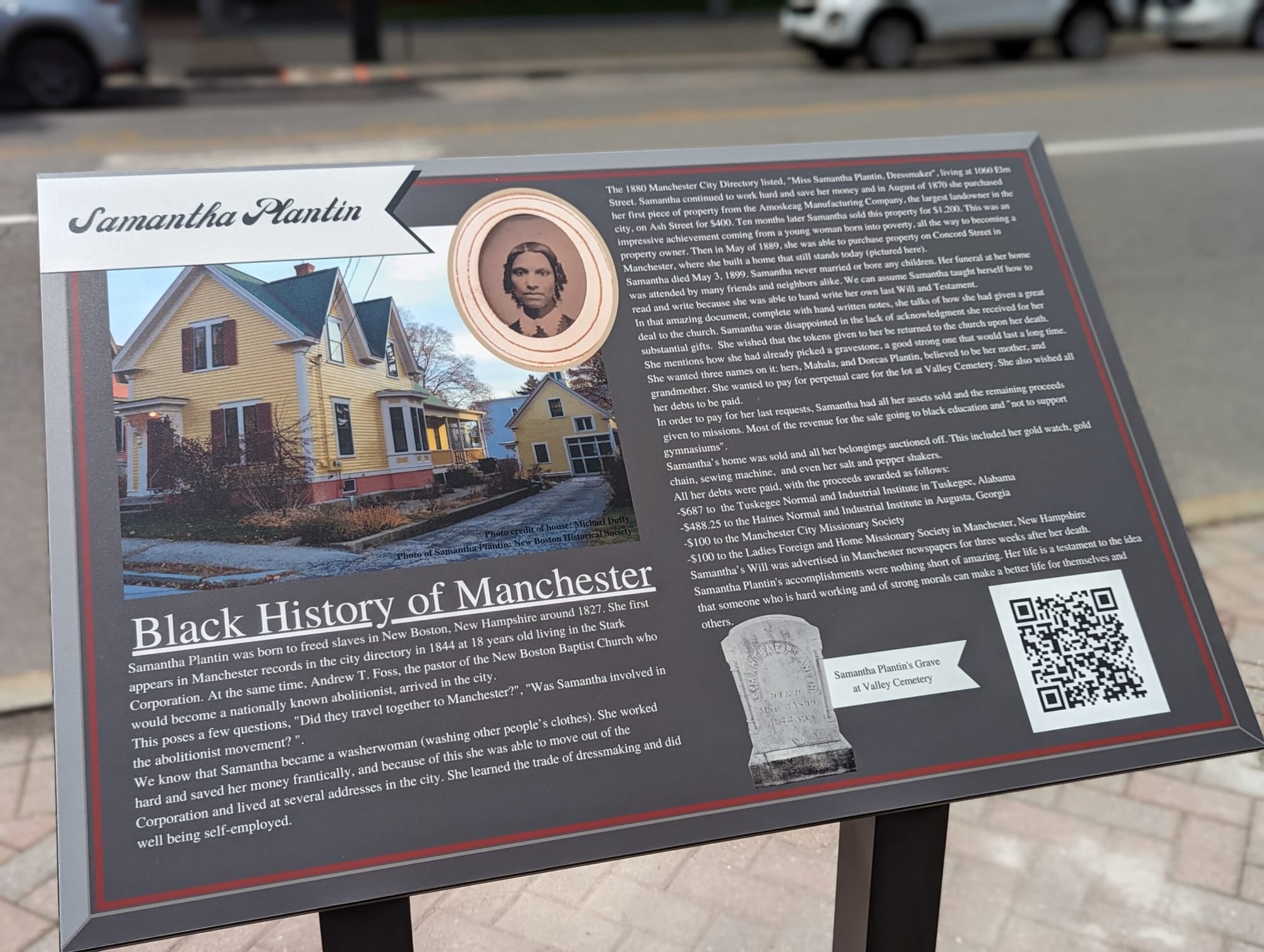

And now, thanks to historian Stan Garrity, everyone and anyone who passes by 1037 Elm St. can learn something about Plantin, whose story, by any measure, is remarkable.

A brief ceremony was held on the corner of Elm and Concord streets Wednesday where the plaque now lives – it was originally to be planted across the street closer to one of Plantin’s former residences. However a building renovation project at 1000 Elm St. meant delaying the ceremony even further, and Garrity is determined to keep this Black history commemorative plaque project rolling.

This is the second such plaque on Elm Street – the first plaque was placed outside The Bookery acknowledging the city’s connection to the Underground Railroad. It sits within range of where Irish immigrant Ann Bamford gave refuge in her home on Manchester Street and safe passage to 42 people who had been enslaved in the South as they made their way to Canada between 1844 and 1858.

As for Plantin’s story, Garrity has done tremendous research to piece together what brought Plantin to Manchester from New Boston in about 1844, which is when her name first appears in city records. She was employed as a “washerwoman,” and lived at Stark Corporation.

She eventually built herself a house on Concord Street which still stands and is currently owned and occupied by Mike Duffy, who spoke briefly about his impression of Plantin based on the construction and condition of her home.

“You can tell how prosperous she was by the carriage house. You can tell clearly from the nails used that it’s newer than the house which means she must have built it and that means she was prosperous enough to have a horse and buggy and two horses,” Duffy said. “We thought it was just an ordinary house. There are plenty of these in town, but it’s really quite significant.”

A QR code on the plaque leads to the Black History of Manchester Facebook page where more documentation about Plantin’s life can be found.

Several people attended the brief ceremony including Shaunte Whitted, who got a special invitation from Garrity. She was originally set to help out with designing the plaques but had to step back from the project for personal reasons. She said she was excited to see the project completed.

“As a Black woman in Manchester it’s phenomenal to see what she did, what she accomplished at such an early time in our city’s history,” Whitted said. “And Stan is just such a wealth of knowledge.”

From her obituary:

“The career of this remarkable woman from the viewpoint of her unceasing labor and energy and her devotion to the church with which she was closely identified for nearly a half-century is decidedly interesting. Miss Plantin came to this city with her mother many years ago. She worked early and late and saved her money. She went out washing at the residences of prominent families and when not doing this she carried the work to her home.”

In her will she basically renounced the church that she had been generous to in her lifetime, feeling they did not reciprocate the gratitude, writing, “I have given a great deal to the church and for things connected with it, for presants (sic) and so on and have no thanks. Am don (sic). They don’t treat me will (sic).”

When she died in 1899 at the age of 70 she left her remaining money and assets to “Black education,” which included donations to Tuskegee Institute in Alabama and Haynes Normal Institute in Alabama.

WATCH: Plaque dedication and reveal, June 14, 2023