Pedals & Pathways: Idaho stop, bike parking, Livingston Park + how a volcanic explosion led to the bicycle

Born near Mannheim, Baron Karl von Drais’ invention was sparked by hardships following The Year Without A Summer, which resulted from the explosion of Mount Tambora, halfway around the world.

Navigating New Hampshire’s Urban Paths

“Get a bicycle. You will not regret it, if you live.”

— Mark Twain

Good old Mark Twain, a reliable smart-ass. The above quote concludes his essay, “Taming the Bicycle,” never published in his lifetime, but eventually included in the 1917 collection What Is Man? and Other Essays. Read more about it, or the entire eight page essay, here.

Now, let’s move on to these topics:

- Idaho Stop in New Hampshire

- Survey & Bike Parking

- Improvements near Livingston Park

- How a Volcanic Explosion led to the Bicycle

Idaho Stop in New Hampshire

New Hampshire House Bill 249 has summary text: “Allowing bicyclists to treat stop signs as yield signs and stop lights as stop signs.”

NH HB249 was voted “Inexpedient to Legislate” on March 26 2025. This status means the bill is now dead.

The full text of the bill may be read at this URL.

Personally, I think this is too bad. Put simply, this law would save lives and reduce injuries. Similar legislation has been adopted by nine states (Idaho, Utah, North Dakota, Washington, Delaware, Colorado, Arkansas, Oregon) with positive results. In Idaho, cyclist injuries from traffic crashes declined 14.5% in one year. In Delaware, crashes involving cyclists at stop signs fell 23% year-over-year. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration report zero evidence showing bicyclist stop-as-yield laws have increased bike conflicts. Getting cyclists through intersections more quickly lessens the chance of conflict and makes all road users safer.

Maybe in future we can craft a version of this law that will NOT be “inexpedient to legislate” in New Hampshire. The lives of our citizens depend on it.

For more info on this issue, I recommend this fact sheet from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

Survey & Bike Parking

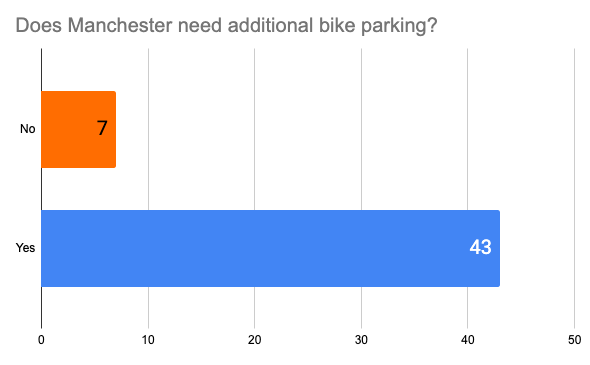

Our survey regarding bike parking in Manchester now has 50 responses. They break down as follows.

Only 14% think no additional parking is needed. 86% of you want more parking.

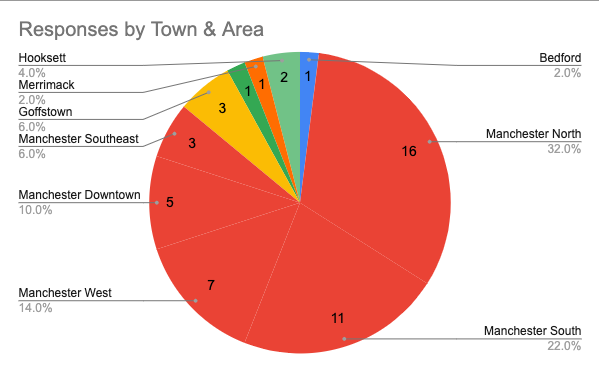

Responses came from all around the area, but the majority came from within Manchester.

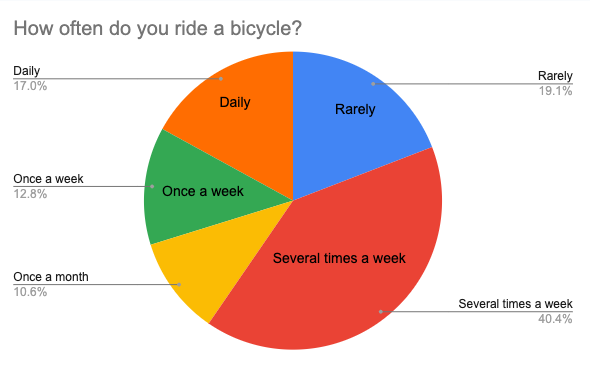

Respondents rode with a wide range of frequencies.

Respondents suggested a great variety of locations where they felt additional parking was needed.

I shared all survey data with Queen City Bicycle Collective, who are sifting through it and looking at funding. While nothing is firm yet, we hope to have additional bike parking on the ground before the end of the year. Our initial focus will probably be in the city’s Central Business District, but locations have not be finalized yet. Stay tuned!

Improvements near Livingston Park

Manchester hopes to make significant improvements to the area of Livingston Park, with a focus on the experience of pedestrians and cyclists. In furtherance of that goal, the city has applied for a Federal Grant to help with funding.

This federal program is called TAP, for “Transportation Alternatives Program.” It is a federally funded initiative to expand access to non-motorized transportation choices that are safe, reliable, and convenient. TAP supports the design and construction of bike lanes, sidewalks, and multi-use paths (including rail-trail corridors) by reimbursing local communities for up to 80% of the costs of these projects. More info on the TAP program can be seen here.

In NH, TAP is managed by state Dept of Transportation, NHDOT.

Manchester’s written application may be viewed here.

Manchester, Goffstown, and Windham have all applied for funding. Applications are under consideration by NHDOT. Multiple legislative bodies and public hearings are involved. Final decisions about funding should become public in summer of 2026.

In the previous round of funding, Nashua’s application ranked second out of 34 received. It was described as follows:

“The purpose of this project is to connect the Nashua Riverwalk with the Nashua Heritage Rail Trail through improvements to an existing paved trail and the construction of a new 10-foot wide paved multi-use path with 5-foot grass buffers on each side. This will provide a vital link between two non-motorized networks that provide access to the City’s 325-acre Mine Falls Park and its miles of paved and natural trails.“

I used to live near Mine Falls Park and can testify to what a great natural resource it is.

Nashua’s Full application can be seen here.

We’ll follow up on these funding applications in future columns.

How a Volcanic Explosion led to the Bicycle

In Indonesia on the island of Sumbawa, early in April of 1815, 210 years ago, a volcano called Mount Tambora exploded.

It was the largest volcanic blast in recorded history, dwarfing the later explosions of Mt. Krakatoa and Mt. St. Helens. The thunderous sounds of detonation were heard in Java and the Molucca Islands at distances of 780 miles and 870 miles. (Imagine being in New Hampshire and hearing an explosion in Chicago.)

Thirty one cubic miles of earth and ash were ejected. The mountain lost 4,000 feet of height. The remaining caldera is 4 miles across and 2 miles deep. Prior to this event, the next largest such explosion had been in the year 180 AD in New Zealand.

Trees from Sumbawa were uprooted and washed into the sea where they mixed with floating pumice and formed rafts up to three miles across. Tens of thousands of people were killed, either burned alive, killed by hurled stones, or dying later from starvation due to ruined crops.

The rising column of ash & smoke reached the stratosphere. Coarser particles settled out, but finer particles remained aloft for months, even years, at altitudes above 33,000 feet. Winds spread them around the globe, where they blocked sunlight and led to three years of planetary cooling. In 1816, a June blizzard struck upstate New York. Killer frosts ravaged New England farms during July and August. London experienced hail all summer. Remains of this global dust cloud can be found in ice strata in Antarctica.

Crops failed around the world. Nations and communities experienced famine, disease, civil unrest and economic decline. New Englanders referred to 1816 as “eighteen hundred and froze-to-death.” Germans called 1817 the year of the beggar.

Around the world, 1816 became known as The Year Without A Summer. It echoed through the arts, in paintings depicting tempestuous and colorful skies. In Switzerland, it produced such cold and stormy weather that English literary tourist Mary Shelley was confined indoors where she dreamed up her lurid tale of Frankenstein.

Southwest Germany was similarly impacted. This came shortly after it had already been ransacked by Napoleon’s armies. As crops failed in the region, the subsequent food shortages led to starvation of both humans and livestock. Tens of thousands of horses starved; others were slaughtered to provide dinner for hungry people. The resulting shortage of draft animals caused transport and industry in Germany to grind to a halt.

Born in Karlsruhe, near Mannheim, Baron Karl von Drais witnessed first-hand all the impacts of the climatic changes. He had studied forestry before moving on to mathematics, physics, and architecture at University of Heidelberg. His job as a Forestry Master afforded him time to tinker and invent. The relatively sudden shortage of horses led Drais to focus his efforts on human-powered transport.

His first few attempts coincided precisely with serious crop failures around the Baden-Württemberg region. Drais’ own notes reveal he was aware that an oat shortage reduced availability of horses, and therefore gave rise to a need for transport that did not rely on draft animals. Drais’ early inventions involved four wheeled vehicles whose drive systems were complex and conveyor-belt driven. His success arrived after radical simplification. Inspired by skating on frozen ponds where, like every skater, he would balance on thin skate blades, he reasoned that a two-wheeled vehicle could be similarly kept upright. He produced a machine with one wheel in front, one in back, and no pedals. The rider’s feet would directly reach the ground, where they could push, à la Fred Flintstone. Notably, the rider could also steer by pushing a bar attached to the front wheel. (Earlier, there had been wheeled hobby horses [“celeriferes”] in France but they lacked steering.) This machine he called his Laufmaschine, or “running machine.” No brakes in the early versions!

He described his machine as twice walking speed and faster than a galloping horse. He demonstrated his Laufmaschine in June 1817, riding it for fifteen kilometers along the best road in Mannheim, completing the trip in a quarter of the usual time. The following month he journeyed around fifty kilometers in four hours.

He took his invention to Paris in 1818 for a demonstration at Luxembourg Gardens. A newspaper described the machine as “quicker than a man running at speed” and said it “ascended with facility the hillocks in some parts of the garden.” The story ran in papers as far away as Pennsylvania.

His Laufmaschine was immediately noticed. Imitations quickly appeared in Britain and America, using names such as “hobby-horse,” “dandy-horse,” and “velocipede.” A British copy made by tradesman Denis Johnson received a patent as an improved version. The Morning Post reported:

“The riding seat, or saddle, is fixed on a perch upon two double shod wheels, running after each other, so that they can go upon the footways … The swiftness with which a person, well practiced, can travel, is almost beyond belief; eight, nine, and even ten miles, may, if asserted, be passed over within the hour, on good, level ground.”

On March 22, 1819, The Bristol Mercury and Daily Post described a benefit of the Drais and Johnson machines: “On a descent, it equals a horse at full speed.” And then, a drawback: “The machine seems to us intended solely for dry level roads. Wherever the ground is broken, hilly or even steep, the rider must dismount and draw his machine after him.” Slowing down and stopping at the end of a descent was another issue.

— Below, Buster Keaton rides a Laufmachine in a short clip, 1:30 —

Popularity peaked in 1819 when there were thousands of these machines in London. Unsurprisingly, this led to problems. On April 19, 1819, The Bristol Mercury and Daily Post reported:

“…as two of these vehicles were descending the hill … with tremendous velocity, one of them came in contact with a lad near the bottom of the hill, who was thrown with such force of the machine, which passed over this leg and fractured it in a most dreadful manner. We lament to add that the rider had not the humanity to take the least care of the unfortunate sufferer, but again mounted his velocipede (which had been upset) pursued his course with the greatest unconcern.”

As curiosity about Laufmachines waned, the public at large remained fearful, for both the rider and bystanders. Or even annoyed: on June 23, 1819, the Poughkeepsie Journal in New York said that this “curious” new invention “is propelled by jack asses, instead of horses.”

Soon, several municipalities in England and the United States prohibited the use of velocipedes on sidewalks, citing the dangers. The fine was “five dollars for every offense” upon the streets of New York, according to an August 11, 1819 story in The Evening Post.

Laufmachines soon fell from popularity. But they were not forgotten. Forty years later, others, mostly in France, improved on Drais’ invention (sometimes called a draisine, or draisenne in French), adding cranks and pedals. Rubber tires were introduced to greatly improve rider comfort over the previous wooden wheels surrounded by iron bands. And after a fit of innovation and improvement in the late 1800’s, recognizable bicycles arrived. Hooray!

The name draisine lived on, used for a human-powered railcar also invented by Drais. Recognizing the contributions of Drais to the development of the bicycle, the Tour de France visited Karlsruhe in 2005. Drais’ innovation was sparked by hardships following The Year Without A Summer, which, thanks to Antarctic ice cores and other meteorological advances, we now know resulted from the explosion of Mount Tambora, halfway around the world.

Geologists say the 20th century was relatively quiet, volcanically speaking. Are we due for an uptick in volcanic activity?

Call for Input

We very much want to hear from you! Do you have any questions or concerns? What topics would you like us to cover? Send your feedback our way and we’ll get on it! We want to ensure this column meets your needs.

Stay safe and have fun out there!

Note: The author is a member of the board of the Bike Walk Alliance of New Hampshire, but the views expressed in this article are his own.