Pedals & Pathways: A cycling celebration, the streets a century ago, legislative updates, etc.

Hard to imagine today, but 100 years ago automobiles were viewed as dangerous toys owned by wealthy scofflaws, running down pedestrians with hardly a thought.

Navigating Manchester’s Urban Paths

“Change is inevitable. Personal growth is optional.”

— Argentinian cyclist at RAGBRAI, who, after going blind, became the stoker (rear rider) on a tandem bike.

How’s that for inspirational? In this edition, let’s talk about:

- Celebrate 10 years of Queen City Bicycle Collective

- Complete Streets for NH

- Streets a century ago

- Upcoming Rides

- Legislative Bill Status

Celebrate 10 years of Queen City Bicycle Collective

The Queen City Bicycle Collective has been keeping Manchester riding — safely, affordably, and together — for a decade. Now, it’s time to celebrate this milestone with staff, volunteers, supporters, and community members. They are expecting a big turnout so be sure to RSVP today.

They’ll be celebrating at the Rex Theatre downtown, always a great venue, on Wednesday, March 12 starting at 5. Brief program at 5:45, live entertainment from 6-8. If you can’t make at 5, come when you can. We expect some yummy treats. All are welcome!

RSVP by clicking this link.

Complete Streets for NH

You may have encountered the phrase “Complete Streets” recently. I was a bit puzzled the first time I heard it. What does it mean for a street to be “complete”?

Complete Streets are streets for everyone. They are designed & operated to enable safe access for all users. Pedestrians, bicyclists, motorists, & public transportation users of all ages & abilities are able to safely move along & across a complete street. Complete Streets make it easy to cross the street, walk to shops, & bicycle to work. They allow buses to run on time & make it safe for people to walk to & from transit stops.

“Complete Streets” refers to an approach to planning, designing, building, operating, and maintaining streets that enable SAFE ACCESS for ALL PEOPLE who need to use them, including pedestrians, bicyclists, motorists and transit riders of all ages and abilities.

As a survivor of a severe cycling accident, I’m a big believer in this concept.

Several communities in New Hampshire have been nationally recognized by Smart Growth America as having some of the best complete street policies in the country. Each community has chosen a different path toward implementing these ideas from City Policy to City Council Resolution. Some of these communities include: Portsmouth, Concord, Keene, Dover, and Swanzey. I personally would love to see Manchester join this list.

Recently, the Southern New Hampshire Planning Commission (often abbreviated SNHPC) has shared several resources to make it easier for NH cities & towns to embrace the ideas in Complete Streets and make roadways safer and more accessible for all users.

Complete Streets have brought several economic benefits to towns that implemented them.

- Each $1 million spent on cycling and walking projects creates 11-14 jobs, whereas $1 million spent on a highway project creates just 7 jobs.

- Protected bicycle lanes led to a 49% increase in retail sales at local businesses.

- Homes with higher Walk Scores sell for $4,000-34,000 more. Just a one point increase in Walk Score is associated with $700- $3,000 increase in home values.

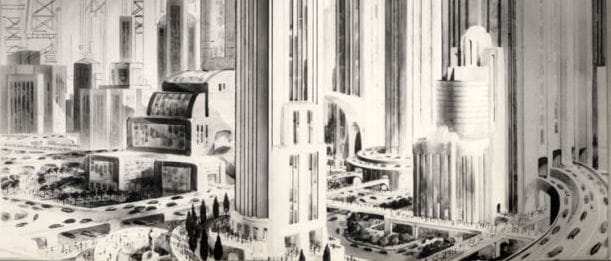

The Streets a Century Ago

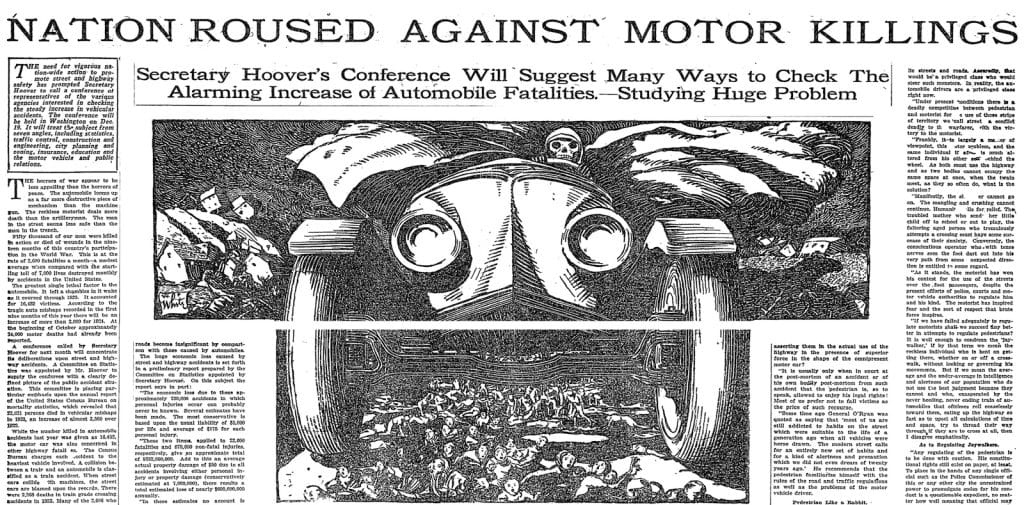

No one remembers it today, in fact it’s hard to even imagine, but in the early 1900s automobiles were extremely unpopular, owing to a small but rising toll of injury and death among pedestrians, and the tendency of many drivers, most wealthy, to travel at unsafe speeds, partly due to a lack of education. The new machines were unaffordable for the average citizen, and were seen as playthings for the rich. A broad anti-car campaign arose that reviled motorists as “road hogs” or “speed demons” and cars as “juggernauts” or “death cars.”

A Different World

Try to imagine: before the advent of the automobile, the streets were peaceful places. Nothing moved faster than 10 miles per hour. Street users were diverse: children at play, pedestrians of all stripes, horse-drawn carriages. Responsible parents would tell their children, “Go out and play,” with little concern.

In the first decade of the 20th century there were no stop signs, warning signs, traffic lights, traffic cops, driver’s education, lane lines, street lighting, brake lights, driver’s licenses or posted speed limits. Our current method of making a left turn was not known, and drinking-and-driving had not even been considered.

Alexander Winton, who made the very first sale of an automobile in the U.S. in 1897, later wrote about attitudes of that time, saying, “To advocate replacing the horse, which had served man through centuries, marked one as an imbecile.” He noted that he was considered “the fool who is fiddling with a buggy that will run without being hitched to a horse.” His banker told him, “You’re crazy if you think this fool contraption you’ve been wasting your time on will ever displace the horse.”

So in the early 1900s, among most people there was little experience with or understanding of speed. Velocity was outside the common experience of most drivers, as was centrifugal force. People did not understand why, when taking corners at high speed, their cars skidded and flipped over (or “turned turtle” in the parlance of the day).

Dangerous Inventions Owned by Wealthy Scofflaws

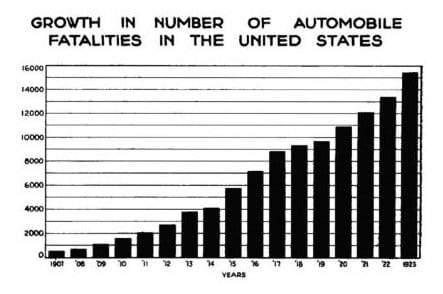

Thus it was little wonder that, when automobiles came, they soon began killing children, and continued to do so, year after year.

The public came to view the car as a death machine, and motorists as flagrantly irresponsible. An editorial cartoon compared the car to Moloch, the god to whom the Ammonites supposedly sacrificed their children. Pedestrian deaths were mourned publicly with large funeral parades. Bells were rung at churches and fire halls. Monuments were built to children who’d been struck down by speeding motorists. But the death toll continued to rise.

In Detroit during one month of 1908, 31 people were killed in car crashes, while the number injured was not recorded. This was recognized as a serious problem. Farmers were reputed to set up roadblocks and booby traps to stop cars from racing down their roads and scaring their horses.

By 1916 one fourth of Detroit’s police force, or 250 officers, was used to manage traffic.

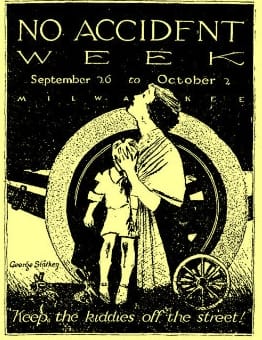

In the 1920s, 60 percent of automobile fatalities nationwide were children under age 9.

In Manchester in 1923, a 5-year old girl was knocked from her bicycle by a car, later dying from her injuries. A generation later, her relatives forbade their own children from ever riding bicycles.

By 1923 it was recognized that in the four years following WWI, more Americans had been killed in automobile accidents than had died in battle in France.

Frightened parents and pedestrians blamed automobiles and drivers. City people were angry. Mobs attacked reckless motorists, and newspapers played up automobile accidents when the victim was easily seen as innocent (a child, a young woman, or elderly), with the driver often portrayed as an unambiguous villain, speed maniac, fleeing criminal, or drunk.

In 1920 the Philadelphia Public Ledger reported that crowds which gathered following an automobile crash always displayed prejudice against the driver.

In a letter to the St. Louis Star in 1923, the writer advised pedestrians to cross the street with pistols pointed at on-coming chauffeurs. Another letter complained that “the pedestrian is forced to submit to the tyranny of the automobilist.”

Also in 1923 the St. Louis Post-Dispatch editorialized that even if a playing child had darted excitedly into the street where he was hit and killed, if then the driver pleaded the accident was unavoidable, such behavior would be “the perjury of a murderer.” The St. Louis Star called motorists involved in pedestrian fatalities “killers.”

In the early 1920s it seemed the general opinion was that the responsibility lay entirely with the motorist.

From the perspective of today, we can see this was a disruption of society brought on by changes in technology. Those changes were rapid: in 1909 the U.S. had 200,000 motorized vehicles; seven years later, in 1916, there were 2.25 million. That’s growth by a factor of 10 in seven years. Since then we’ve seen many other technological disruptions, most causing far fewer fatalities, still often leading to societal changes. But in the early 20th century such disruptions were not well understood.

A Marketing Campaign

Those who stood to profit from the business of automobiles, and related businesses, heard the growing public outcry and realized it was a threat to their profit.

The president of the Chicago Motor Club warned his friends that bad publicity over traffic casualties could soon lead to “legislation that will hedge the operation of automobiles with almost unbearable restrictions.” The solution was to persuade city people that “the streets are made for vehicles to run upon.”

So like all good capitalists, they took action. Their challenge was to alter the public perception, to replace thousands of years of seeing the street as a place for people walking and draft animals pulling carts, where cars were violent intruders, and instead shift to a vision of the street as the rightful place for fast-moving machines where it was the responsibility of bumbling pedestrians to watch out for machines, not vice versa.

They were clever. They even invented a whole new concept: jaywalking. Prior to the advent of automobiles, there was no concept of a crosswalk, no need to cross the street only at prescribed locations. So this idea was conjured by automobile clubs and car manufacturers to cultivate a notion that roads were for cars, not people. It was pedestrians who needed to be controlled and who bore responsibility for accidents. In those days the word “jay” meant “a greenhorn, or rube.” So a jaywalker was a pedestrian who lacked understanding and didn’t know how to behave properly.

Often the proponents of the automobile presented their position clothed in a rhetoric of freedom. In the American ideals of political and economic freedom, automotive proponents discovered the rhetorical lever they needed. Motorists, while a minority, had rights that protected their choice of travel mode from intrusive restrictions. Their driving also constituted a demand for street space, which, like other demands in a free market, was not a matter for expert scrutiny.

The Campaign Succeeds

The transformation from the anti-automobile mood of the early 1900s to the perception of streets as space for motorized traffic was amazingly quick and efficient. Resistance to automobiles was portrayed as “anti-progress” and “old-fashioned.” The tide turned and by the 1930s public sentiment was shifting in favor of automobiles and drivers.

Cities everywhere were spending significant public funds on widening streets, building broad boulevards, increasing curb parking, and altering the rules of the road to restrict pedestrians and give more rights and space to cars. Separated, elevated freeways became the vision of the future, though it would take some years before they began to build them all over the country.

Pedestrians, cyclists, and others who had previously been free users of public roads were quite literally pushed to the sidelines. Worse, many died merely from having the temerity to venture forth on those public roads, which once had been safe for all. Perhaps worst of all, their deaths went from being loudly proclaimed & memorialized to being barely noticed, just another statistic to be ignored in America’s rush to embrace everything that even vaguely smelled of progress.

Today, in the total time since the automobile was introduced, nearly 4 million people have died in the U.S. in crashes, or ten times the number of American soldiers killed in WWII. Our annual fatality rate surpassed 40 thousand in 1963, then vacillated a few percent each year, from a high of 54 thousand in 1972 to a low of 32 thousand in 2011. In 2023 it was 41 thousand.

In what other industry would such a death rate be acceptable?

Upcoming Rides & Events

It’s never too early to start planning!

- Taco Tour, with valet bicycle parking. Thu, May 8 — 4 – 8 p.m.

- Trans-NH Bike Ride: Cycling to End Muscular Dystrophy, June 20 – 22, 2025

- Tri-State Trek: The Ride to End ALS, June 21 – 22, 2025

- Manch Pride Parade & Festival, Sat, June 28 – 11 a.m. – 5 p.m.

- Manch Citywide Arts Festival Arts & Crafts Fair. Sat, Sep 13, 10 a.m. – 5 p.m.

- Tour of Manchester. Sunday, September 14, 2025

Legislative Bill Status

Below are legislative status updates on two of bills regarding transportation.

1) Personal Electric Vehicles. House Bill 715, Relative to personal electric vehicles. Referred to the House Transportation Committee, where it was deemed “Inexpedient to Legislate.” This effectively kills the bill.

This bill attempted to address safety relating to all of the following: “electric unicycles, electric scooters, electric skateboards, electric hoverboards, Segways, Onewheels, and electric skates.”

2) Idaho Stop. House Bill 249, Allowing bicyclists to treat stop signs as yield signs and stop lights as stop signs. Referred to the House Transportation Committee, where it is scheduled for further discussion on Tuesday March 4th at 10 AM in Room 203 of the Legislative Office Building.

If you would like to testify about this bill, contact your state representative.

We wrote about this bill in January. It would bring the so-called “Idaho Stop” to New Hampshire. This law allows cyclists to essentially treat a stop sign like a yield sign, not needing to come to a complete halt, but yielding right-of-way, and then able to proceed after ensuring the intersection is clear. Eight other states have passed similar laws. These laws do not negate a cyclist’s responsibility to yield to other traffic before crossing an intersection and to follow all work zone traffic rules.

Worth noting: After Idaho adopted the law, cyclist injuries from traffic crashes declined by 14.5% the following year. Delaware passed a similar law in 2017, and traffic crashes involving cyclists at stop signs fell by 23% in the next 30 months.

Coverage by Keene Sentinel here.

Call for Input

We very much want to hear from you! Do you have any questions or concerns? What topics would you like us to cover? Send your feedback our way and we’ll get on it! We want to ensure this column meets your needs.

Stay safe and warm and have fun out there!