New England Wildlands report focus is on giving nature a chance

“The story of New England is a story of rejuvenation, rewilding and a second chance,” John Leibowitz, of Northeast Wilderness Trust, said. The only thing that determines what may be Wildland is the commitment and decisions of humans. “We have the power to commit to any land,” he said.

New Hampshire is 85% forest, with huge swatches of jaw-dropping geography, but little of it is as protected as people may think, including the fragile area above Mount Washington’s fragile tree line.

New Hampshire Wildlands vulnerability is just one small part of the extensive Wildlands of New England report released Wednesday, the result of a three-year and ongoing effort to identify land in the six-state region that meets specific criteria for intent, management and level of protection that will preserve it permanently.

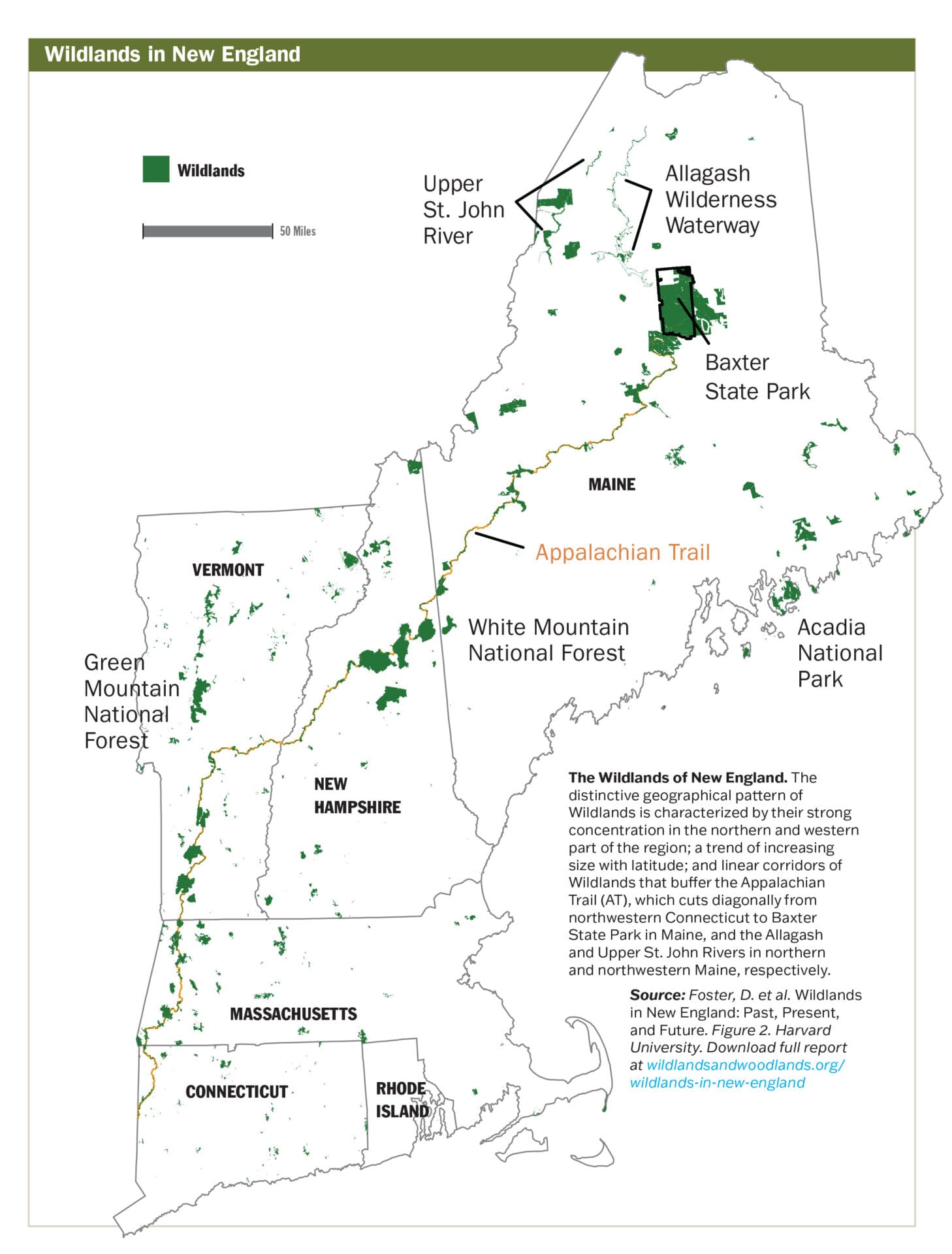

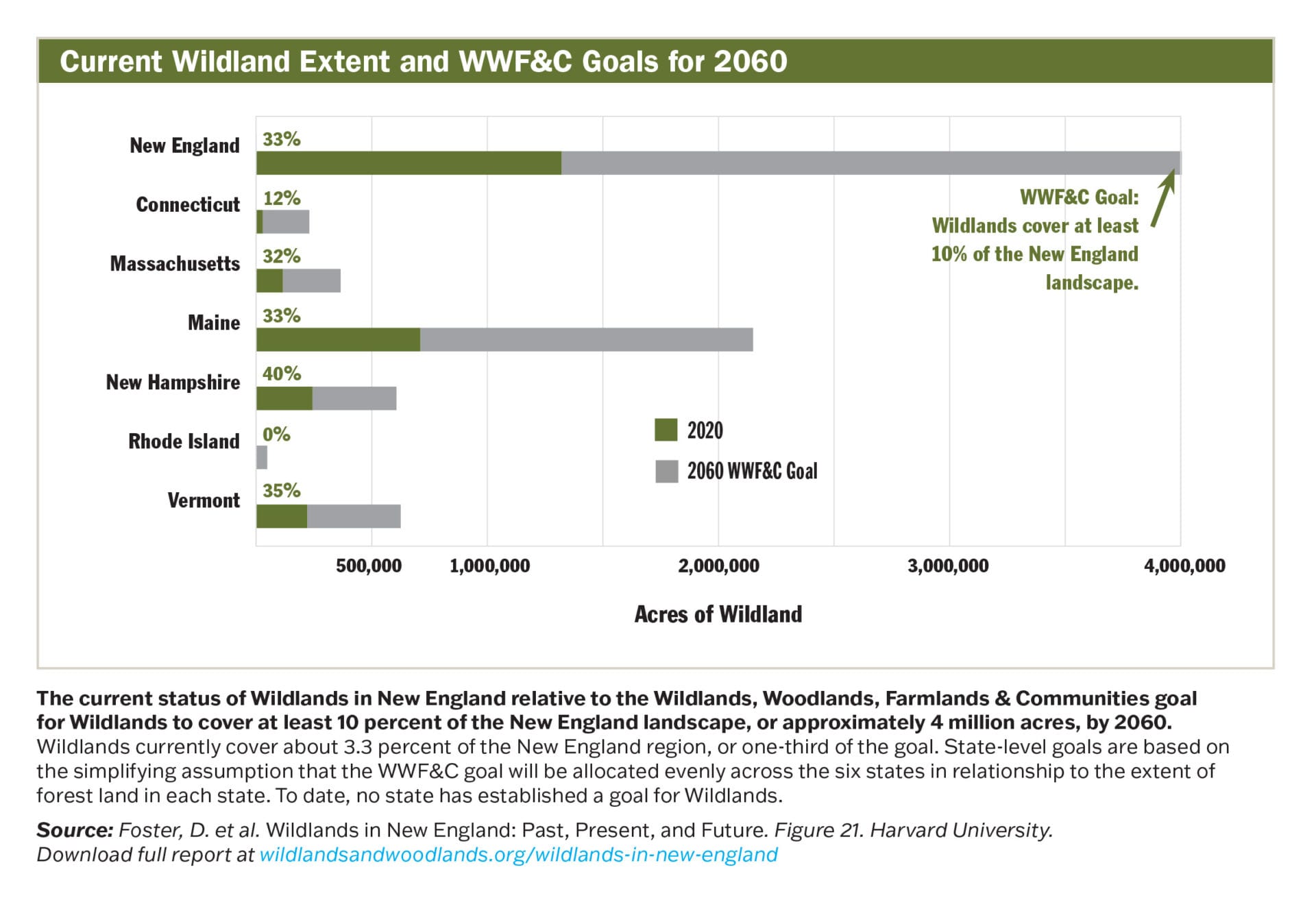

The study by Wildlands, Woodlands, Farming and Community Initiative determined that of New England’s 40 million acres, 81% is forested, but only 3.3% meets the initiative’s criteria to be Wildlands. The goal is to increase that to 10% by 2060, or even 20%, as land preservation efforts gain steam.

To do that, the report’s authors said, humans will have to have some humility, sit back, and let nature do what it does best. Often the best approach “is just letting nature thrive on its own,” David Foster, of Harvard Forest, one of the report’s authors, said.

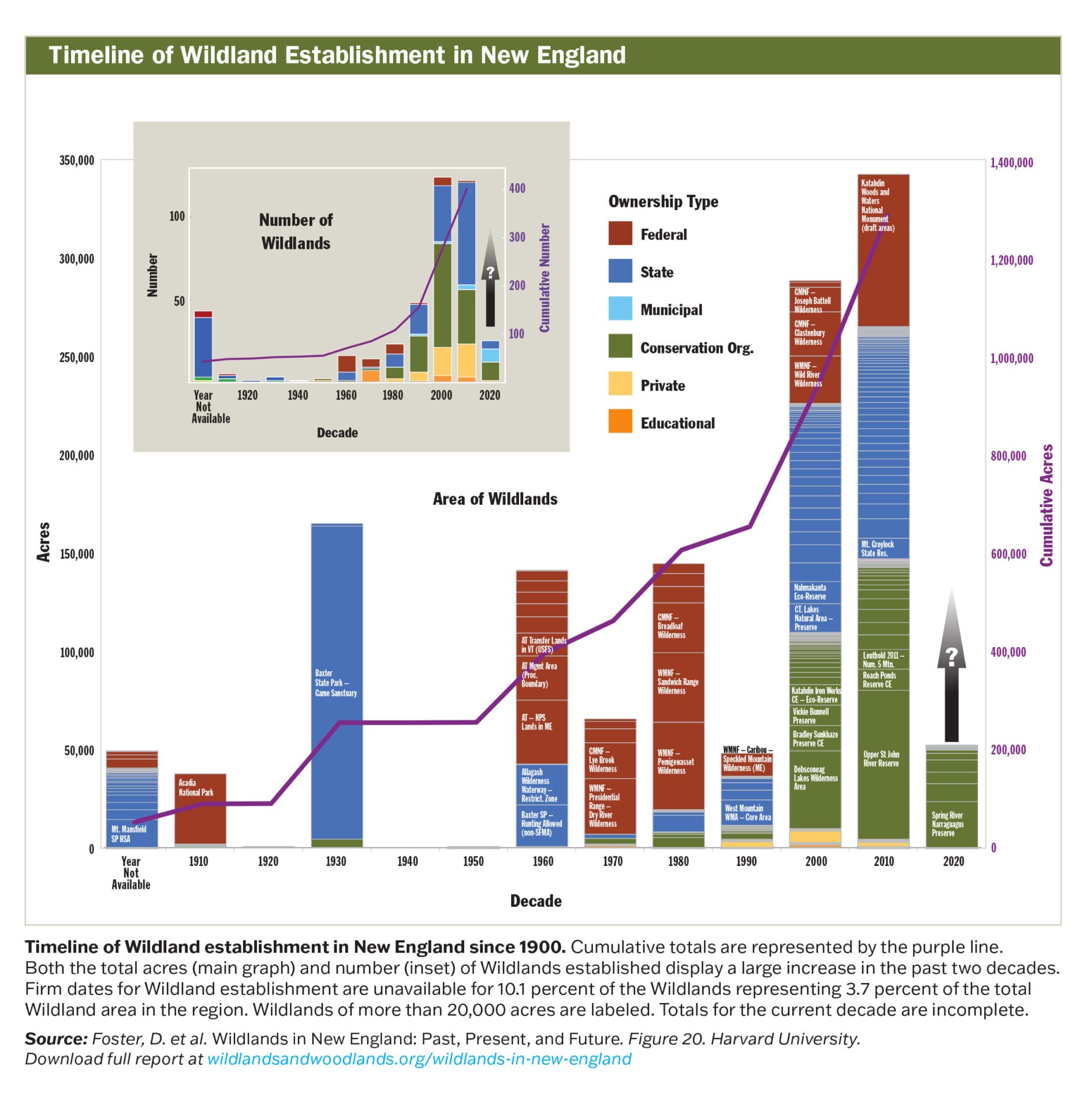

The study included 426 individual municipal, state, federal, and private properties that comprise New England’s Wildlands, and is the first in the U.S. to document all Wildlands in a region, its creators say. The report’s goal is to support land planning, climate and conservation policy, and action that will lead to more protected land.

The initiative was led by Highstead, a regional conservation nonprofit, Harvard Forest, The Nature Conservancy, Northeast Wilderness Trust and other conservation organizations.

The message at a webinar Wednesday introducing the report was positive, despite the fact climate change, increasing development, lack of policy focus and other factors threaten natural areas. Land conservation in New England is increasing substantially, with more land than ever protected, including many that are “rewilding” after they were used for industrial purposes.

“The story of New England is a story of rejuvenation, rewilding and a second chance,” John Leibowitz, of Northeast Wilderness Trust, said. The only thing that determines what may be Wildland is the commitment and decisions of humans. “We have the power to commit to any land,” he said.

Of the reasons protecting Wildlands is important, “Paramount among them is that, for many, such places hold immense intrinsic value — wild nature simply has a right to exist, as do all of the species that inhabit wildlands,” the report said.

Other critical reasons are that they are essential for maintaining and increasing biodiversity, they mitigate climate change by storing large quantities of carbon, enhance landscape resilience, offer quiet space for spiritual or physical renewal and serve as reference sites for scientific inquiry and the development of ecological approaches to forest management and conservation.

“Collectively, these benefits and values make Wildlands indispensable,” the report said.

Wildlands vs. wildland

Wildlands has many definitions with just as many contexts. The report’s definition of Wildlands is “tracts of any size and current condition, permanently protected from development, in which management is explicitly intended to allow natural processes to prevail with ‘free will’ and minimal human interference.”

The report adds, “Humans have been part of nature for millennia and can coexist within and with Wildlands without intentionally altering their structure, composition, or function.”

The report, as well as Wednesday’s panel, stressed that the concept of Wildlands “embraces the enduring presence of Indigenous groups in New England.” Indigenous people lived in concert with the land for 10,000 years, “living for millennia in reciprocity with the whole land community, including old and majestic forests that allowed the full diversity of life to thrive.”

When the Europeans arrived four centuries ago, that all changed. “Wildland conservation, like all of conservation, is only necessary due to unchecked development and destructive practices — first introduced to this region by colonizing people — that have threatened all natural systems and society itself.”

It’s also important to understand that Wildlands work complementarily with woodlands, farming and other land functions, and that they can be used for low-impact recreation.

The study focused on where New England’s Wildlands are, what their characteristics are and their current protection status. Besides establishing a definition, it identified all the land it could fitting the definition and established an open-source database and map to continue the research.

Acadia? Yes. Mount Washington? No.

The largest Wildlands tract in New England is 159,000 acres of Maine’s 209,000-acre Baxter State Park. One of the smallest is 322-acre Muddy Pond Wilderness Preserve in Kingston, Massachusetts.

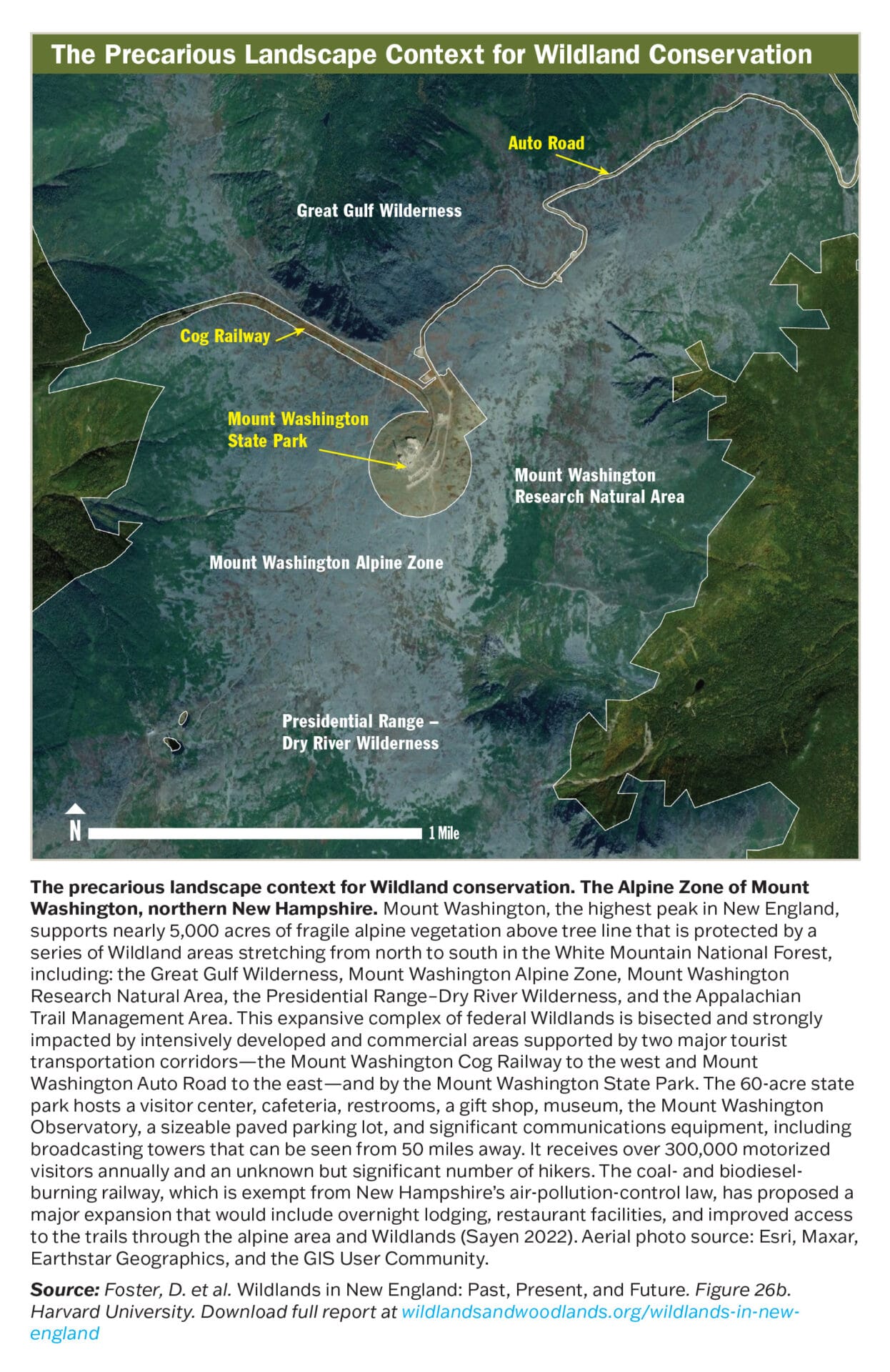

It may surprise people that Acadia National Park in Maine, with 4 million visitors a year and an auto road up Cadillac Mountain, qualifies as Wildland. But the summit of Mount Washington, with 300,000 visitors a year and surrounded by White Mountain National Forest, does not.

At Acadia, “The majority of the park is managed in a manner consistent with Wildland criteria, and large areas support natural process and offer valuable habitat, quiet retreats, and spectacular vistas,” according to the report.

Meanwhile, Mount Washington has nearly 5,000 acres of fragile alpine vegetation above the tree line that is protected by five federal Wildland areas, but “this expansive complex of federal wildlands is bisected and strongly impacted by intensively developed and commercial areas.” Those include the Mount Washington Cog Railway, Mount Washington Auto Road and 60-acre Mount Washington State Park, which has a visitor center, cafeteria, restrooms, a gift shop, museum, the Mount Washington Observatory, a large paved parking lot “and significant communications equipment, including broadcasting towers that can be seen from 50 miles away.”

“The coal- and biodiesel-burning railway, which is exempt from New Hampshire’s air-pollution-control law,” and the major expansion its owners have proposed, threaten the mountain’s ecology further, the report says.

Other Wildland areas are squeezed by unprotected land that threatens their status, including the 2,190-mile corridor of the Appalachian Trail, a Wildland that’s bordered mostly by land that isn’t.

While private conservation efforts have increased, strengthening public policy that protects wildlands is key, according to the report. Of New England’s 1.3 million acres of wildlands, 75% is state or federal land. Of the 36% that is state controlled, the amount of protection provided varies dramatically, depending on the state.

New Hampshire “pioneered the idea of public reacquisition of land in the eastern United States” a century ago when a Harvard professor managed to preserve 17 acres of old-growth forest in what is now Pisgah State Park, the report says.

But now, in New Hampshire, the state “plays a minor role in state land conservation strategies, which emphasize active management and resource economics.” Most of the New Hampshire’s Wildland area – 75% – is managed by the federal government, with only 12% managed by the state, and the rest by conservation groups.

Massachusetts controls 90% of its Wildlands, but state protection statutes, while they exist, are largely unused. In Maine, on the other hand, the 41% of Wildlands that is state-owned is 90% protected by state statute.

That’s just a small example of the mish-mash of approaches and protections to Wildlands that those behind the report are hoping to bring into focus. Land conservation efforts were largely led by the federal government and states, but conservation groups began getting more involved around 1980, and that effort really picked up 20 years ago.

An illustration of a Wildlands that has all the right elements, the report says, is the 10,500-acre Vickie Bunnell Preserve, in Columbia and Stratford. It has size, ecological diversity, is adjacent to Nash Stream State Forest, and critically, is held in a third-party easement, which offers permanent protection. Owned by The Nature Conservancy, it’s secured by a Forest Legacy easement held by the state as well as a “forever wild” easement held by Northeast Wilderness Trust.

The combination with the state forest makes it a 40,000-acre block of unfragmented forest, which includes a high-elevation spruce forest that includes more rare and endangered species than any site in the state. It also has 13 mountain peaks above 3,000 feet and habitat for less-common species like pine marten and Bicknell’s thrush, according to The Nature Conservancy.

The preserve was created in 2001, and is TNC’s largest New Hampshire holding. It was named for Bunnell, a Columbia select board member and judge, who loved hiking in the area, particularly on Blue Mountain, which is now Bunnell Mountain. She died in the 1997 Colebook shooting that also took the lives of newspaper editor Dennis Joos and State Troopers Scott Phillips and Leslie Lord.

Where to Go From Here

The purpose of the report isn’t just to protect existing Wildlands, but to encourage creation of new ones.

The initiative’s goal for New Hampshire is that its Wildlands will increase from 233,000 acres, 4.1% of the state’s land, to 10.6% by 2060, and that the amount of conserved woodland that isn’t Wildland, which is about 30% of the state’s land, will double. The initiative hopes to increase the amount of Wildlands in New England to 4 million acres.

New England’s Wildlands are in remote and rural areas of the region that aren’t great for agriculture – mountains, bogs and remote forests. The report seeks to spread the word that Wildlands can be created anywhere.

Leibowitz said that for a diverse ecosystem, “we ought to look at other kinds of land.”

“We need to be talking about it in downtown Boston, and we need to be talking about it in northern Maine,” David Foster, of Harvard Forest, said Wednesday.

The report’s goal is not to tell stakeholders how to do protect and create Wildlands, but to get them engaged in doing it, Wednesday’s panel said.

The study found more stakeholders than they’d realized they would, panelists said. These include policy makers, land trusts, landowners, funders, philanthropists, conservation organizations and individuals.

The research isn’t stopping with the study’s release, Liz Thompson, a Vermont ecologist, said. “We’re ready to receive your information,” she told the nearly 400 people who’d tuned in, many of them members of conservation organizations, government agencies, and other groups and individuals involved in conservation.

The report also includes an online interactive map that she said she hopes stakeholders will add to.

Overall, the initiative hopes to:

- Center Wildlands in an integrated approach to land planning and conservation that includes actively managed forests and farms and sustainably designed communities supported by a low-carbon, demand-reduction economy.

- Strengthen existing Wildlands by developing clear intent, reinforcing unique qualities of management, increasing protection in perpetuity by adding permanent legal protections to current Wildlands enhancing the landscape setting for Wildlands as part of a regional connected network.

- Advance Wildland conservation, significantly, thoughtfully, and strategically by:

- recognizing history when establishing conservation goals

- building relationships, and learning from, indigenous and local communities

- embracing humility, allowing nature to manage itself

- ensuring diverse landowners and groups are included in conservation

- advancing policy at local, state, and federal levels

- increasing public and private funding for integrated approaches to land planning and conservation.