Manchester childhoods, changed by 2 notorious murders, frames new novel

Gail Walsh Chop and Margaret Corbett Wiley grew up in a city stricken by the murders of two teenage girls and five decades later, they’ve turned it into the coming-of-age novel ‘Flashbulb Memories.’

MANCHESTER, NH – Gail Walsh Chop and Margaret Corbett Wiley met as 14-year-olds the first day of freshmen year at Immaculata High School in Manchester and immediately bonded over one of the city’s most sensational murder cases.

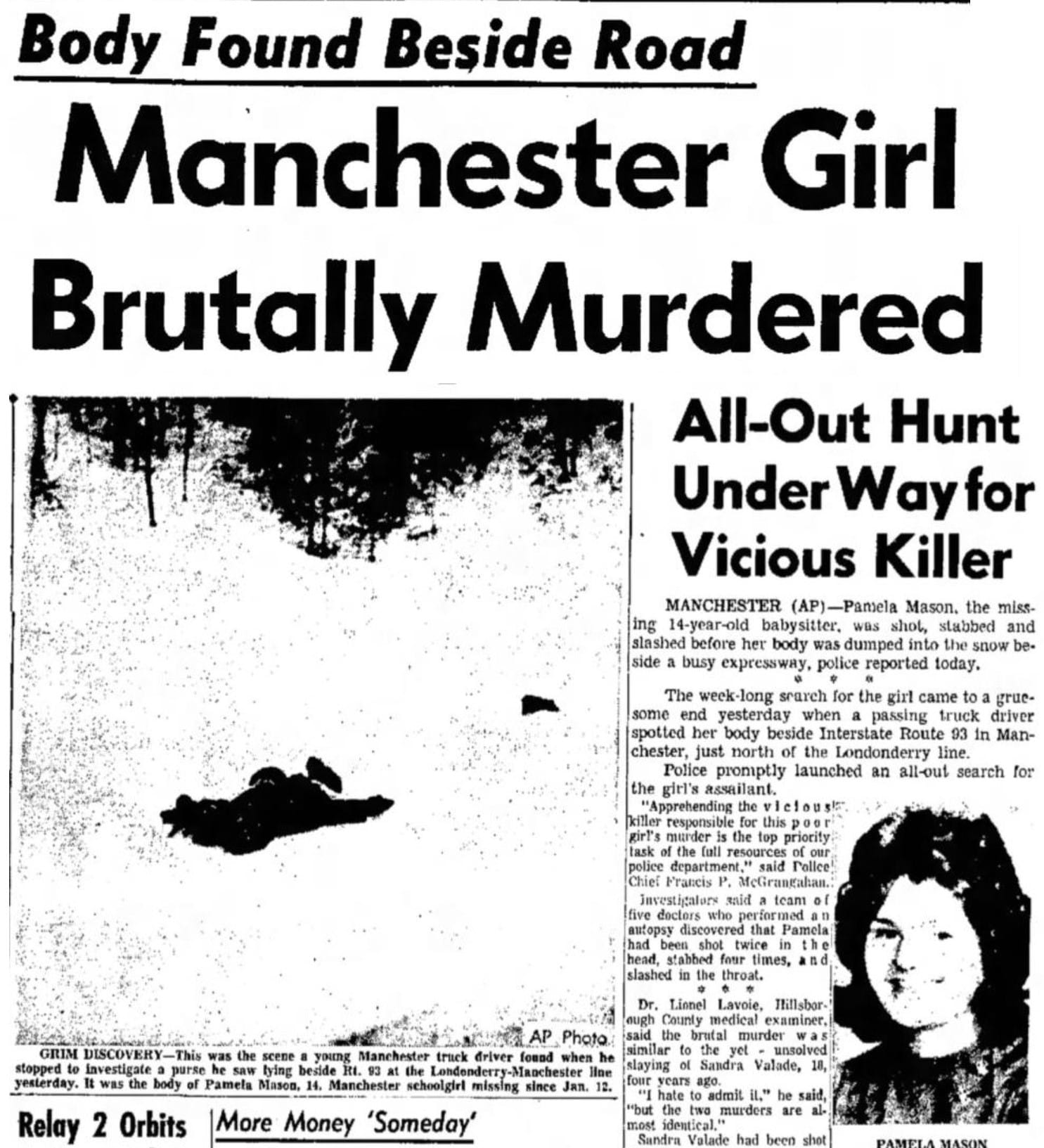

The friendship, as well as the fascination with the murders of Sandra Valade and Pamela Mason, continued over the decades. Now, nearly half a century later, the two Manchester natives have channeled both into their debut novel, “Flashbulb Memories,” a coming-of-age story about growing up in Manchester in the 1960s under the shadow of a double murder case that many feel never achieved justice for the victims.

“When we met, when we were 14, at Immaculata, you start talking and trying to build common bonds that interest you, in developing a friendship,” Chop said as the two authors sat down with Manchester InkLink for an interview in Maine, where they both live. “Edward Coolidge and the murder of these girls is something that percolated right to the top.”

They each wanted to find out what the other knew. “We compared stories, we compared takeaways from the whole ordeal, because parents, you know, parents didn’t share any information back then,” Chop said.

Coolidge was convicted for the 1964 murder of Mason, 14, in 1965. He was indicted for murder in the 1960 death of Sandra Valade, 18, but the state eventually dropped the charges. The murders riveted the city. Coolidge’s life sentence was overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1971, and though he pled guilty to second-degree murder and served for another 20 years, it outraged many who had followed the case.

“Flashbulb Memories,” only focuses a little on the legal aspects of the case. The story, told from the point of view of young Nora Donovan, focuses instead on how the murders and their aftermath affected a generation of Manchester children. Nora is eight years old in 1960, when Valade was killed, and her interest in the case is bolstered by the fact that her father is a Manchester police detective.

The book, with chapters divided by year, begins in 1960, and follows Nora as she grapples with her own vulnerability as well as the larger issue of violence against women as the two Manchester murders, as well as others across the country, unfold.

Nora and her family are fictional characters, but they have deep roots in Chop and Wiley’s Manchester childhoods. Both grew up in in Irish Catholic families on Manchester’s East Side at the same time Nora was. Their lives were framed by the city’s neighborhood culture, the Catholic schools and churches they attended, and more, just like Nora’s was.

A child’s point of view

Neither Wiley nor Chop were professional fiction writers when they set out to write “Flashbulb Memories,” though both had written professionally in the context of their careers.

Chop is retired as vice present of patient care services at Maine Medical Center in Portland. Wiley was an ICU nurse for 38 years, as well as a professor at Colby-Sawyer College in New London.

Wiley had always had an interest in creative writing, including taking a course with Joni Cole, who runs The Writer’s Center in White River Junction, Vermont. She also taught freshman composition.

Wiley and Chop had been kicking around the idea of a book for years, but in 2019, during a trip to Ireland, Wiley decided it was time to act. While she had the creative writing itch, Chop is “the queen of verbs” and the perfect choice for a collaborator, Wiley said.

They got an unexpected boost from a local attorney who’d intended to write a nonfiction book about the cases, but never did. He gave them all of his research materials.

“We decided early on we’d have a child narrate it,” Wiley said, because of the loss of innocence theme, as well as the fact it’s the lens through which they both viewed that time in Manchester.

All the facts relating to Valade and Mason, their murders, and Coolidge, are true. Many of the other stories, including interactions with nuns and other details of daily life in the book are also drawn from their own experiences, or those of family and friends. They worked hard to give a lot of attention to detail regarding landmarks and businesses, many of which are long gone but some of which still remain.

The two also had family connections to the case, including Chop’s stepfather, William Craig, who had to recuse himself shortly after he was appointed to defend Coolidge because of a conflict of interest at his law firm.

“Many, many people, including my sister and my mother, had contacts with Eddie Coolidge,” Wiley said.

Other, more unexpected, connections arose. For instance, Chop worked at Maine Medical Center with someone who was originally from the West Side, and when she wrote to him to ask him if he’d known Pamela Mason, it turned out he had a significant detail to impart.

The connections didn’t end after the book was completed.

“Since we published this book, people have been getting in touch with us, sharing memories of how terrified they were,” Wiley said.

Those memories include police coming to schools to talk to students, connections with the victims, as well as connections with Coolidge himself.

People are also connecting with the book itself. “All these women are writing to us, saying ‘I was Nora,’” Wiley said.

While Coolidge and the murders frame the book, in the end, it’s about much more, the authors acknowledged.

Wiley paraphrases Stephen King: “He said something like, ‘Anyone who can remember their childhood can be a novelist.’”

In many ways, the murders and their aftermath had a lasting impact on their generation, not only for things like being afraid to walk down the street at night and locking doors that they never locked before, but also making them realize that they couldn’t always trust what they were being told by adults.

“It was a whole loss of innocence,” Chop said.

Manchester area residents can meet the two authors when they hold a book signing from 4 to 6 p.m. Saturday, May 13, at The Bookery, 844 Elm St. They also plan to be at the Carpenter Library at a date not yet determined.

[table id=60 /]