Manchester Black history plaque honors 2 men named Caesar, both 18th-century landowners

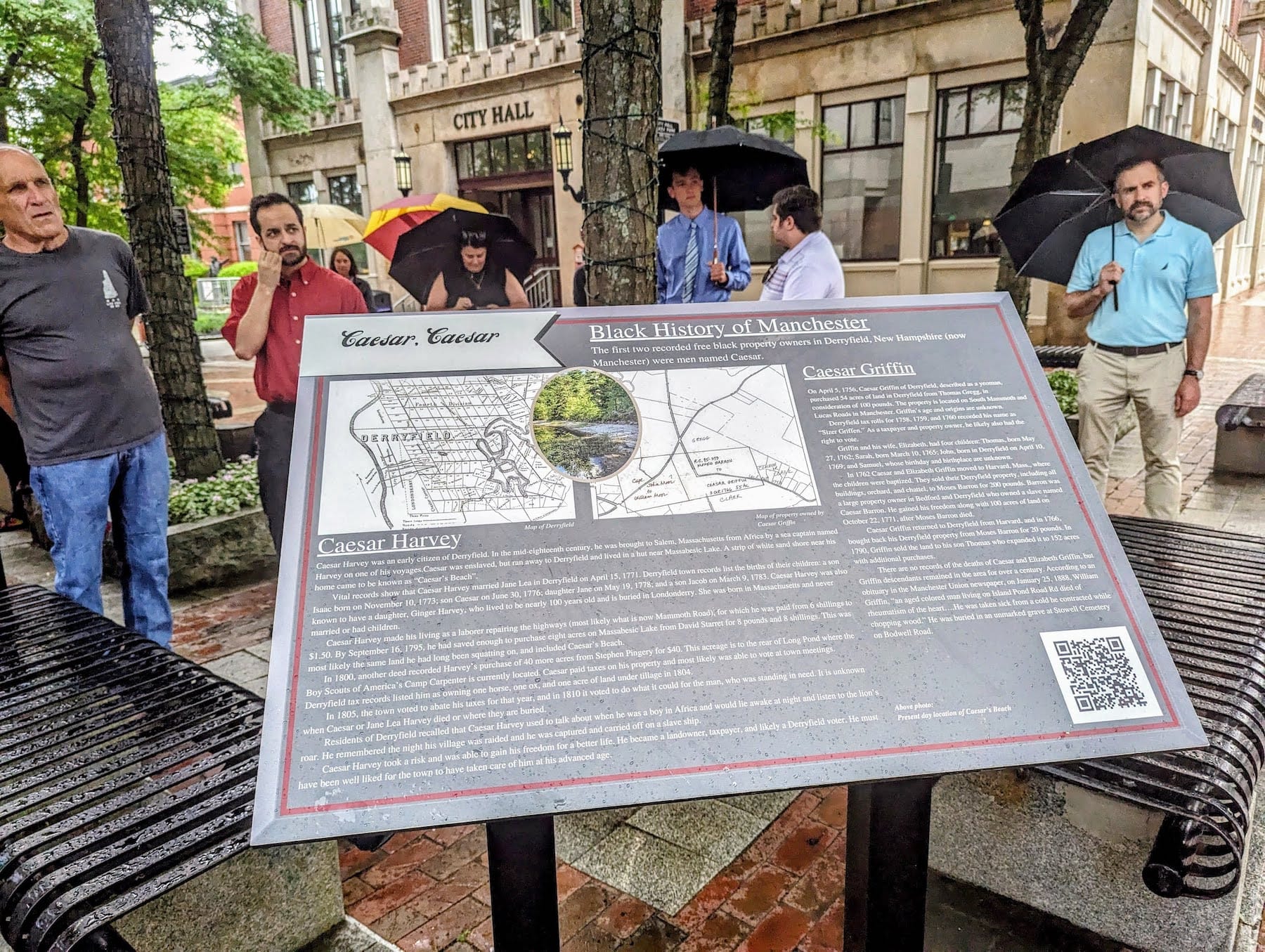

The fourth in an ongoing series of Black History plaques was unveiled on June 14 at City Hall Plaza, named “Caesar, Caesar,” honoring Caesar Griffin and Caesar Harvey – two Black residents of Derryfield during the 1700s, who Garrity has identified as Manchester first Black landowners.

MANCHESTER, NH – When you hear “Caesar, Caesar” your brain might think “pizza, pizza,” but historian Stan Garrity would have you think of two important men named Caesar, whose places have now been secured in the city’s historical record.

The fourth in an ongoing series of Black History plaques was unveiled on June 14 at City Hall Plaza, named “Caesar, Caesar,” honoring Caesar Griffin and Caesar Harvey – two Black residents of Derryfield during the 1700s, who Garrity has identified as Manchester first Black landowners.

Garrity explained that just before the Revolutionary War a census was taken and Manchester – then known as Derryfield – had a population of 285. Of those, 140 were male, 142 were female and three were enslaved blacks for life. Of the 140 males were two free Black men named Ceasar Harvey and Caesar Griffin. The new plaque tells part of their stories.

“I’m sure they knew each other – there were only 285 people in Derryfield at the time and they didn’t live far from one another. I’m sure they went to the Meeting House together at Mammoth and Sommerville,” says Garrity.

The plaque uses maps to show the location of both properties – Caesar Griffin purchased 54 acres from Thomas Gregg on a plot of land in the area of South Mammoth and Lucas roads. Griffin and his wife Elizabeth, had four children – Garrity says they are likely the first Black children born in Manchester and Griffin’s descendants remained in the area for the next century.

Caesar Harvey escaped his enslaver, a sea captain who brought him to Salem, NH. Harvey found his way to a piece of land in Derryfield on the edge of Lake Massabesic, where he became a squatter. He eventually married and had five children, and he worked as a highway laborer, most likely working on what is now Mammoth Road. He saved enough money to purchase 8 acres of land on Lake Massabesic, Garrity says likely the land he squatted on years earlier – and which is still identified as Caesar’s Beach on maps.

A historical narrative of each of the Caesar’s can be found below.

The ambitous sign project was made possible primarily through Garrity’s persistance, but he gives credit to the city’s Community Improvement Program and a grant from the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 for funding the plaques. Garrity has over the years researched extensively and gathered enough Black history for many more signs. Although the initial grant is running out this year, tax deductible donations to continue this project can be made through the Manchester Historic Association, earmarked “Black History of Manchester.”

Garrity’s “thank you” list extends to the 2021 Board of Mayor and Alderman for approving this project; the current Board of Mayor and Alderman for their continued support; Kristy Ellsworth of the Manchester Historic Association, who designed the sign; Garrity’s niece Courtney Rosso; Jeff Barraclough, Executive Director of the Millyard Museum; Mark Mastromarino the museum’s librarian and historian; Mark Birmingham who drew the map of Caesar Griffin’s property; Kate Waldo from Parks and Recreation; Todd Davis of the city’s facilities department; Chris Belanger and Chris Gupul, who installed the sign; and Garrity’s family, for their ongoing support.

“I’ve uncovered so much history – I’ve discovered that we had a big underground railroad operation here in Manchester and an incredible number of abolitionists,” Garrity said. “I’m sure the same is true for a lot of New England towns, but it’s especially exciting to find out so much history of Manchester that was lost. It would be a great Netflix series for our city.”

Garrity is conducting a “Walking Through Manchester’s Black History” tour on July 26, a two-mile route that starts at the City Library on Pine Street.

“Anyone who finds this as interesting as I do should come to the tour,” Garrity says.

A historical narrative of the life of Caesar Griffin

On April 5, 1756, Caesar Griffin of Derryfield, described as a yeoman, purchased 54 acres of land in Derryfield from Thomas Gregg, in consideration of 100 pounds at 45 dollars. The property is currently located on South Mammoth and Lucas roads. Griffin’s age and origins are unknown.

Derryfield tax rolls for 1758, 1759, and 1760 recorded his name as “Sizer Griffen.” As a tax payer and property owner, he might also have had the right to vote.

Griffin and his wife Elizabeth had four children: Thomas, born on May 27, 1762; Sarah, born March 10, 1765; John, born in Derryfield on April 10, 1769; and Samuel, his birthday and birthplace are unknown.

In 1762 Caesar and Elizabeth Griffin moved to Harvard, Mass., where the children were baptized. They sold 200 pounds of new tenure money their Derryfield property, including all its buildings, orchard, and chattel, to Moses Barron. Barron was a large property owner in Bedford and Derryfield. He also owned a slave named Caesar Barron, who gained his freedom along with 100 acres of land in a deed on October 22, 1771, after Moses Barron died.

Caesar Griffin returned to Derryfield and on October 3, 1766, and bought his Derryfield property back from Moses Barron for 20 pounds. Then on April 10, 1790, Griffin sold the land to his son Thomas who expanded it to 152 acres with additional purchases.

There are no records of the deaths of Caesar and Elizabeth Griffin. We do know that Griffin descendants remained in the area for over a century. On January 25, 1888, one William Griffin, “an aged colored man living on Island Pond Rd, died taken sick after chopping wood.” He was buried in an unmarked grave at Stowell Cemetery on Bodwell Road.

A historical narrative of Caesar Harvey

From the Manchester Historic Association Collections, Volume 1, page 81: “As long ago as when slaves were held in Massachusetts, one Harvey, a sea captain of Salem, brought to that town on one of his voyages a negro, to whom he gave the name Caesar. This negro ran away and came to live near these pines in a hut near the lake, and from him the strip of white sand shore has taken and retained the name Caesar’s beach.” It is unknown when Caesar came to Derryfield and squatted on that piece of land on the edge of Massabesic Pond (now Massabesic Lake).

In a September 18, 1919, speech to the Manchester Historic Association, school principal William Huse stated that Caesar Harvey used to talk about when he was a boy in Africa and would lie awake at night and listen to the lion’s roar. He remembered the night his village was raided and he was captured and whisked off to a slave ship.

Vital records show that Caesar Harvey married Jane Lea in Derryfield on April 15, 1771. Derryfield town records list the births of their children: a son Isaac was born on November 10, 1773; a son Caesar on June 30, 1776; a daughter Jane on May 19, 1778; and a son Jacob on March 9, 1783. Caesar Harvey was also known to have a daughter, Ginger Harvey, who lived to be nearly 100 years old and is buried in Londonderry. No records were found of Ginger’s birth, but the 1860 U.S. Census states she was born in Massachusetts. She never married and died childless.

Caesar Harvey made his living as a laborer repairing the highways (most likely what is now Mammoth Road), for which he was paid from 6 shillings to $1.50.

By September 16, 1795, he had saved enough to purchase from David Starret, for 8 pounds and 8 shillings, 8 acres on Massabesic Lake. This was most likely the same land he had long been squatting on, and included Caesar’s Beach. Another deed, of September 13, 1800, recorded Harvey’s purchase of 40 more acres from Stephen Pingery for $40. This acreage is in the rear of Long Pond where the Boy Scouts of America’s Camp Carpenter is currently located. Caesar paid taxes on his landed property and most likely was able to vote at town meetings. Derryfield tax records listed him as owning one horse, one ox, and one acre of land under tillage in 1804.

In 1805, he must have fallen on hard times, for the town voted to abate his taxes for that year, and in 1810 it voted to do what it could for the man, who was standing in need. No records have been found of Caesar Harvey’s or Jane Lea Harvey’s deaths or of where they are buried.

Caesar Harvey took a risk and was able to gain his freedom for a better life. He became a landowner, a taxpayer, and probably also a Derryfield voter. He must have been well liked for the town to have taken care of him at his advanced age.