Lewiston shooting report highlights ‘missed opportunities’ by sheriff, Army Reserve

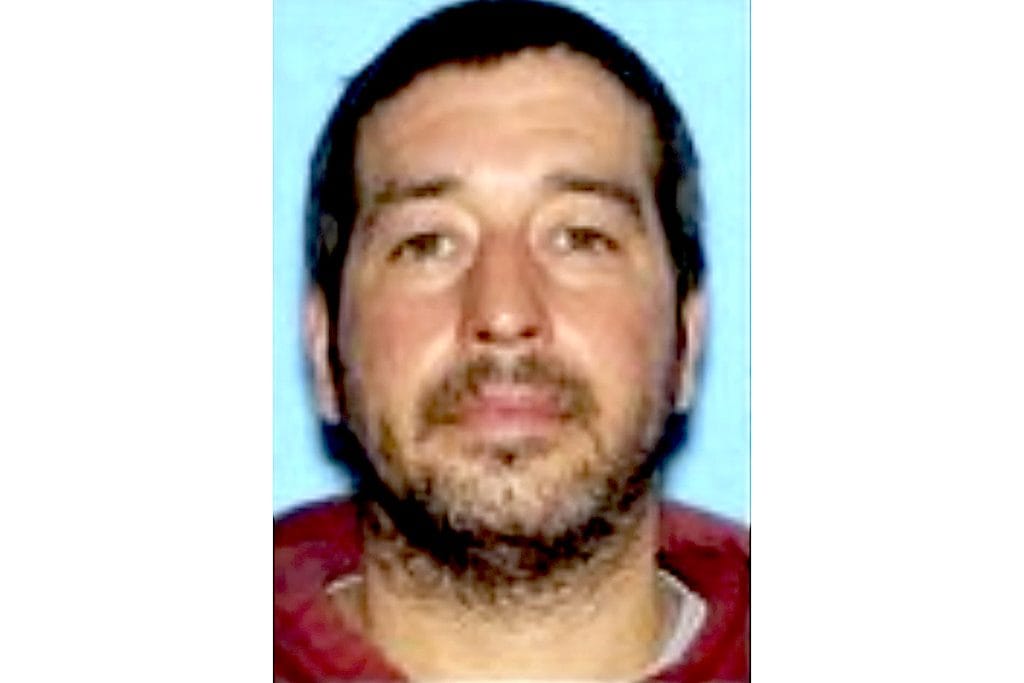

Robert Card is responsible for the October shootings that took 18 lives in this city, but a report released Tuesday highlights the failings of his Army Reserve unit and local sheriff’s department, both of which dropped the ball on addressing Card’s mental health issues and access to guns.

LEWISTON, Maine – Robert Card is responsible for the October shootings that took 18 lives in this city, but a report released Tuesday highlights the failings of his Army Reserve unit and local sheriff’s department, both of which dropped the ball on addressing Card’s mental health issues and access to guns.

“Robert Card is totally responsible for his own conduct. Solely responsible,” Daniel Wathen, head of an independent commission that investigated the shootings said Tuesday. Wathen said that it can’t be known if Card would have still committed a mass shooting even if someone had managed to remove his guns. “But the commission unanimously finds that there were several opportunities that, if taken, might have changed the course of these tragic events,” Wathen said.

The independent commission, set up in November by Gov. Janet Mills, released its 215-page final report at a news conference at Lewiston City Hall Tuesday. It had spent the past nine months holding both public and private hearings investigating the shootings. It had the power to issue subpoenas, and witnesses testified under oath.

Wathen said that the report can spur changes that may prevent future similar tragedies.

Mills said, “Our ability to heal — as a people and as a state — is predicated on the ability to know and understand, to the greatest extent possible, the facts and circumstances surrounding the tragedy in Lewiston. The release of the Independent Commission’s final report marks another step forward on that long road to healing.”

The report faulted the Sagadahoc County Sheriff’s office for not seizing Card’s weapons and placing him in protective custody under Maine’s yellow flag law after his ex-wife and teenage son in May 2023, and members of his Army Reserve unit in September 2023, reported that he was having alarming mental health issues, making threats and had at least 10 guns.

Maine’s yellow flag law, at the time, requires someone who suspects a gun owner is an imminent threat to report them to the police. The police, if they believe there is probable cause, may take the person into protective custody and order a mental health evaluation from a medical expert. If the expert and police agree it’s necessary, they can apply to the court to get the guns temporarily taken away. After the shootings, the law was amended to allow law enforcement to get the court order without the mental health assessment.

The report also faulted the Army Reserve unit for not following up after Card was hospitalized for more than two weeks during a training trip to New York three months before the shooting after he threatened fellow reservists and exhibited other mental health issues. The reserve didn’t follow up on recommendations by the hospital, including making sure Card didn’t have access to guns.

Aside from amending the yellow flag law, Mills and the Maine State Legislature also passed laws after the shooting that extend a background check for private sales, institute a 72-hour waiting period on buying guns and budgeted more money to address mental health.

Multiple failures

On Oct. 25, 2023, Card, 40, fired 18 rounds in 45 seconds from a .308 Rugar small frame autoloading rifle in Just-in-Time Recreation, a bowling alley, at 6:54 p.m. There were about 60 people in the building, 20 of them children. He killed eight and wounded three.

He then went to Schemengees Bar and Grille, where at 7:07 p.m., he fired 36 rounds in 78 seconds, killing 10 and wounding 10 more.

In total, Card killed 18 people and wounded 13 in less than two minutes inside those businesses. At least 20 others were injured trying to escape the shooting, the report says.

Several law enforcement officials testified “that the yellow flag law is cumbersome, inefficient, and unduly restrictive regarding who can initiate a proceeding to limit a person’s access to firearms.”

It also acknowledges that the Army Reserve didn’t share all the relevant information it had about Card’s behavior with the Sagadahoc County Sheriff’s Department, which may have made them try harder to file a yellow flag report.

“Nevertheless, under the circumstances existing and known to the [sheriff’s department] in September of 2023, the yellow flag law authorized the department to start the process of obtaining a court order to remove Card’s firearms,” the report says.

“The Commission further finds that the leaders of Card’s (Army Reserve) unit failed to undertake necessary steps to reduce the threat he posed to the public. His commanding officers were well aware of his auditory hallucinations, increasingly aggressive behavior, collection of guns, and ominous comments about his intentions.

“Despite their knowledge, they ignored the strong recommendations of Card’s Army mental health providers to stay engaged with his care and “make sure that steps are taken to remove weapons” from his home. They neglected to share with the SCSO all the information relating to Card’s threatening behavior, and actually discounted some of the evidence about the threat posed by Card.

“Had they presented a full and complete accounting of the facts, the SCSO might have acted more assertively in September,” the report says.

The report also suggested that Maine State Police review the response to the shooting and search for Card, who was found dead from a self-inflicted gunshot wound two days later in nearby Lisbon.

“The challenges faced by law enforcement in responding to the shootings were unprecedented in Maine,” Wathen, a former Maine Supreme Court Chief Justice, said. “While many demonstrated bravery and professionalism in the face of danger, the first hours after the shootings were, at times, utter chaos as hundreds of law enforcement officers poured into Lewiston and were dispatched or self-dispatched to numerous scenes throughout the area.”

Many of the victims were also members of Maine’s deaf community, who had a weekly cornhole tournament at the bar that Card targeted. The report details failures in communicating with victims and those who escaped the bar, because they had no provision for communicating wit them.

Timeline leading to Lewiston shootings

Card joined the Army Reserve in 2003, and was a sergeant first class at the time of the shootings. In 2013, he became a trainer and every summer worked with West Point Military Academy’s incoming cadets, teaching them cadets how to properly throw live hand grenades. “Over the course of his career, Card was present when thousands of live grenades were thrown each year,” the report says.

In the months leading up to the shootings, according to the report:

May 2023: The Sagadahoc County Sheriff’s Department Deputy Sheriff Chad Carleton was told by Card’s ex-wife and son that he was exhibiting increasingly paranoid, delusional and threatening behavior. They were concerned, because Card owned 10 to 15 guns. Carleton talked to officials in Card’s Army Reserve unit, because Card had his monthly reserve assembly coming up. First Sgt. Kevin Mote, the commanding officer, who was also an Ellsworth police officer, said they’d noticed the same behavior. Carleton posted a report to the rest of the department that warned to use caution if approaching Card. He tried to contact the Army Reserve officials again, according to the report, but got no response.

Meanwhile, Card’s sister attempted through May, June and July to find a way to get help for Card, including through the VA, but wasn’t successful. At one point, someone at the VA told her not to tell Card’s command about his delusions that people were calling him gay or a pedophile, because it could harm his career. She tried extensive online searches, she could not find clear information on where to report her concerns and much of the online information was outdated. She also left five voicemail messages at his unit’s headquarters, in Saco, but no one ever called her back.

July 6, 2023: Card bought the .308 Ruger SFAR rifle with a scope and laser that was later used in the shootings, and a 9mm Beretta pistol from Fine Line Gun Shop in Poland, Maine. The purchase was legal under Maine law, because he’d never been involuntarily hospitalized and had no felony criminal record, domestic violence protection order, or weapon restriction order that would have prohibited it. [If the state’s yellow flag law had been triggered after the initial complaints, he wouldn’t have been able to buy the guns].

July 15, 2023: Card and his Army Reserve unit arrive at Fort Smith, in New York, for training. Card immediately begins to exhibit paranoia, including saying the woman at the front desk and clerks at rest stops on the trip there from Maine were accusing him of being a pedophile.

“Members of his unit tried to tell him that was not happening, but he did not believe them,” the report says. “Many members of his unit found his behavior and statements odd and disconcerting.”

His paranoia escalated to the point where he accused other members of his unit of talking about him the same way, then attacked one member, who was a good friend. Card locked himself in his room and after Mote and another officer attempted to talk to him and get him out of the room, they eventually contacted New York State Police for help. Eventually, Cpt. Jeremy Reamer, the company commander, who was at his home in New Hampshire, approved a mental health evaluation, and Card was taken to a military hospital in West Point, New York.

An examination by psychiatric nurse practitioner, Matthew Dickison, who is an Army captain, determined he was exhibiting psychosis and paranoia and needed further examination. He was taken to Four Winds Hospital in Katonah, New York, where he agreed to be voluntarily committed.

Dickison told Reamer that the reserve must make sure that Card attends all follow-up appointments; increase supervision; encourage Card to temporarily secure his personal weapons with MPs, arms rooms, or other trusted sources; and restrict access to or disarm all military weapons.”

Dickison also told Reamer that Card was not fit for duty. He later told the commission that Reamer appeared to understand the recommendations, expressed no concerns about his ability to carry them out, and gave the impression that he would follow them.

Card was hospitalized until Aug. 3, 2023, and while there showed “risk factors and high-risk psychosocial issues requiring immediate intervention” including “active thoughts of homicidal ideation.”

During this time, Dickison talked again with Reamer, discussing taking steps to make sure weapons were removed from Card’s home. Reamer didn’t have any questions, Dickison told the commission.

“I was all about making sure the service member didn’t have access to weapons,” Dickison testified.

Four Winds Hospital officials also urged Reamer to make sure that Card did not have any weapons, the report says.

“Reamer neglected to follow any of the recommendations Dickison gave him,” the report says. “In fact, he ignored them. Nor did he complete the Developmental Counseling Form (DA Form 4856) that, among other things, directed Card to make and maintain regular contact with his case management team. Reamer failed to follow up with treatment providers, failed to read email messages concerning Card, failed to heed the advice of the providers to ensure the removal of all firearms from Card’s home, failed to contact the [Sagadahoc County Sheriff’s Office] or have other members of his unit who were law enforcement officers in Maine contact the SCSO to arrange for the removal of the weapons, and failed to follow up with Card to ensure that he was participating in treatment.”

Reamer later testified that his email was not working and that his “computer was down” in the three months between Card’s hospitalization and the shooting, the report says.

Upon his release from the hospital, on Aug. 3, Card promised to take medication, which had shown some signs of helping, and also follow up. But he did neither, according to the report. After the shootings, investigators found his prescription medication almost completely untouched.

Aug. 5, 2023: Card picked up a silencer he’d previously ordered from Coastal Defense Firearms in Auburn, Maine. Federal law required him to fill out a form that asked, among other things, if he’d been committed to a mental health institution. He answered yes, and they did not sell him the silencer. He later told others that he was mad about that.

Sept. 13, 2023: Card and fellow reservist and good friend Sean Hodgson, who worked with him at First Fleet, an Auburn trucking company, were together in a car when Card, who was driving erratically, became angry, pounded the steering wheel, and punched Hodgson in the face. Hodgson got out of the car and walked home. He called Reamer and reported what happened, but Reamer took no action. He also spoke to another officer and reported what happened.

Sept. 15, 2023: Hodgson sent a text to Reamer and Mote that said: “Change the passcode to the unit gate and be armed if sfc card does arrive. Please. I believe he is messed up in the head. And threaten the unit other and other places. I love to death but do not know how to help him and he refuses to get help or continue help. …And yes he still has all his weapons…I believe he is going to snap and do a mass shooting.”

Mote wrote to the Sagadahoc sheriff’s office about his concerns over Card, with Hodgson’s text warnings attached.

Mote, who is an Ellsworth police officer, also Ellsworth police detective Corey Bagley, who opened an investigation into Card’s threats against Mote and his reserve unit. Mote prepared a detailed narrative outlining all that had happened with Card in the previous months. He told the commission that he intended that narrative to be “a statement of probable cause” so the sheriff could use it to secure a yellow flag order. Because Mote was involved in getting Card hospitalized in New York, he thought it best to have another officer initiate contact with the Sagadahoc County Sheriff’s Office.

Bagley tried to reach Sagadahoc County deputy Carleton, who’d done the report on Card in May, but he wasn’t available, so he spoke to Sgt. Aaron Skofield, who went to Card’s home in Bowdoin, arriving at 3:09 p.m. No one was home. He went to Card’s father’s home, but Card wasn’t there, so went back to Card’s at 3:24 p.m. Again, no one was home.

At 5:11 p.m. Skofield broadcast a statewide File 6 notice, which alerts other law enforcement to dangerous people, that said: “Caution, officer safety, known to be armed and dangerous. Robert has been suffering from psychotic episodes and hearing voices. He is a firearms instructor and made threats to shoot up the National Guard Armory in Saco. He was committed over the summer for two weeks due to his altered mental health state, but then released…If located use extreme caution, check mental health wellbeing and advise Sagadahoc.”

Sept. 16, 2023: Card’s unit had its monthly assembly in Saco, but Card had told Reamer he wasn’t going to attend. Saco police went to the armory in case Card showed up. Reamer downplayed Card’s issues to them, according to the report.

At 8:45 a.m., around the same time the Saco police officers were at the armory, Skofield and a deputy from neighboring Kennebec County went to Card’s residence. Card’s car was there, and they heard someone moving around inside, but he wouldn’t come to the door, so they left after 16 minutes.

Later that morning, Skofield spoke with Card’s father, who said he did not know where Card’s guns were. The deputy tried to reach Card’s brother, but couldn’t. The deputy called Reamer, who did not tell him Skofield that the mental health providers recommended that Card not have access to weapons. He told Skofield, “I don’t think this is gonna get any better,” but also appeared to minimize the risk that Card posed to the community, according to the report.

Sept. 17, 2023: Skolfield spoke to Card’s brother and sister-in-law, who told him that Card’s guns had not been removed. Card’s brother, Ryan Card, told Skofield he’d try to secure them. Skolfield also asked Ryan to determine whether Card needed a psychiatric evaluation and to report his observations back to Skolfield, but Skolfield made no plans to follow up and didn’t contact Ryan Card further to find out if the guns had been removed.

The report says, “At that point, Skolfield decided there was no need for him or the [sheriff’s department] to be involved any further. He considered the matter ‘resolved,’ stating that no person expressly said that he or she ‘wanted to press charges.’”

The report says that Skolfield notified his supervisor, Lt. Brian Quinn, who deferred to his “judgment as an experienced officer” and did take any further action other than notifying his supervisor, Chief Deputy Brett Strout. Strout did not take any further action.

“Skolfield failed to follow up with Ryan Card, did not attempt another well-being check, did not consult with the District Attorney’s Office about the possibility of a yellow flag order, and did not contact the [Army Reserve] unit or any of its members for further information. He failed to read Carleton’s report from May. Skolfield left on vacation on September 18, 2023.”

The report also notes that month, the sheriff’s department and other area law enforcement agencies entered into a contract with a mental health specialist who was hired specifically to provide services, advise officers on mental health matters, and function as a liaison between the department and individuals.

“The goal of this contract was to assist officers handling mental health cases and to get citizens in distress the help they needed,” the report said. But the mental health specialist was never consulted or used in Card’s case. And though Skofield and others had received National Alliance on Mental Illness weeklong Crisis Intervention Team training, they didn’t make use of that training while dealing with the Card situation.

Oct. 1, 2023: Skofield returned from vacation and closed the case.

Oct. 18, 2023: At 8:54 a.m., Skofield canceled the File 6 notice that warned other law enforcement about Card.

Oct. 19, 2023: While making a delivery to a warehouse in Hudson, New Hampshire, Card told two employees that he knew they were talking about him, even though neither had said anything to him or about him. He told them, “Maybe you will be the ones I snap on.” [They reported the incident to the Hudson Police Department in the early morning hours of Oct. 26, after one of them recognized Card’s photo on the news.]

Oct. 23, 2023: Bagley, the Ellsworth police detective who Mote had asked to put together the information for the yellow flag report, asked Mote about the open case. Mote told him that nothing had been done about Card. He said that Card would be “forced out [of the reserves] with a discharge” in the next few days. Mote also said he didn’t know of any new threats against him by Card. Bagley closed the case.