Immigrants Among Us: Why they come to America

This entry is part [part not set] of 13 in the series The Immigrants Among Us [http://manchester.local/inklink-series/the-immigrants-among-us/] From the interviews conducted for this series, we learned of the individual motivations and reasons why people depart from their homelands. What is evident

From the interviews conducted for this series, we learned of the individual motivations and reasons why people depart from their homelands. What is evident from these conversations is that America is perceived as the destination for the future. Future survival, future prosperity, future education, future safety, and a future for families and children.

According to figures from the Congressional Budget Office net immigration to the U.S. was 2.6 million in 2022 and 3.3 million in both 2023 and 2024. Most are coming as temporary workers, students, or individuals who are joining their families in the country. There are H-1B visas for specialized occupations, H-2A for agricultural workers, and F-1 and J-1 visas for students. Lawful permanent residents of the United States can sponsor relatives to immigrate here using the family-based visa system.

The path to America is rarely easy. We hear immigration described in terms of “invasion” and “overwhelming numbers” and the numbers are arguably significant but only represent a small fraction of displaced people. For each person that arrives, countless numbers cannot escape their origins.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) as of May 2024 worldwide, there are more than 120 million people who have been forcibly displaced as a result of conflict, persecution, violence, or human rights violations.

- 43.4 million refugees

- 63.3 million internally displaced people

- 6.9 million asylum seekers

- 5.8 million people in need of international protection, a majority from Venezuela

This volume will increase as the world begins to experience more natural disasters associated with climate change, something described by the United Nations as “the multiplier effect.” Extreme weather events like floods and droughts and the resulting disruption of food production combined with factors like conflict, limited economic opportunities, and politics will drive more migration, according to the UN, on the effects of climate change and population displacement.

Each immigrant has their reasons, motivations, or fears that drive them from their home countries. Some come because of opportunity, they come to “make it” in America; to have a “better life” for their children. Many are escaping danger, oppression, and poverty. For some, it is simple; for others, the obstacles can be insurmountable.

The U.S. immigration system is complex. Marry a U.S. citizen and you’re in. Attempt to escape political persecution and you can languish in legal limbo for decades. Arrive undocumented and you could be granted amnesty; Today you may have Temporary Protective Status but what happens to that protection in 2025 under the Trump administration remains to be seen.

Refugees and asylum seekers go through screening procedures that take months – even years – with a low probability guarantee of successful application.

Nepalese refugee Lochan Sharma who was born in a refugee camp and came here as a child says that once they received U.S. visas their destination of New Hampshire was not by choice, saying, “It was just where they put us. I think my parents had a choice of, like which country, but where in the country was not a choice we were given. That’s where the resettlement program was, so that is how we came to New Hampshire.”

One African family, now in Concord, languished for years in refugee camps in Benin describing their experience, “People from Lutheran Services, working with the United Nations, came to us in the camps, and then they were speaking with us about the program. So they will come and then they will take photos, passport photos. And then we did the fingerprinting, you know, the criminal record check, and then the hospital, they checked us to make sure that we are healthy.”

Glory Wabe, a nurse from the Philippines, talked of the challenges and motivations for immigration.

“What I can say is that immigrating to the country is not really easy. I mean, it’s difficult, very difficult. And especially in my case, I had to leave my family, but I wanted to check out how it was, how it was to be working in some other country because I had the ability and skills to do it. I tried it and I liked it.”

“I think lots of immigrants really are very helpful to this country. If you look at it, wherever you go now, especially hospitals, hospitals are full of Filipino nurses, and doctors. And I think for as long as the immigrants are coming in here in the legal way, they should be treated nicely. Yeah. Simply because you know, we’re here, we’re here to help, you know, to help the economy.”

Immigrants are driven to protect themselves, to rescue their children from harm. Most commonly express a desire to build a future for their children and families.

The path to naturalization is long

The path to legal status for someone born outside the U.S. can be long and challenging after arriving here with either a green card, an asylum visa, or undocumented.

Sebastian came here from Peru on a seasonal worker visa and then remained after it expired and lived in undocumented status for many years. He described the stress of living in the shadows, of living on the fringe of the economy. Ultimately he attained legal status and is now a naturalized citizen.

“It’s definitely scary. You think about it, you know, you can wake up one morning, have a cup of coffee, go to the store, and that might be the last time you see your family, you know because you can be sent back home right away.”

Immigrants can apply for naturalization citizenship after five years of being a green card holder or lawful permanent resident. About three-quarters of green card holders ultimately become citizens. In fiscal year 2023, the U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Services (USCIS) agency held naturalization ceremonies for 878,500 new citizens.

One reason the process is so long is the lack of legislation enacted to contend with the migration issues of this moment. President Ronald Reagan signed the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), the last major update of the immigration system in 1986.

And yet in the ensuing 38 years, demographics, economics, geopolitical conditions, and technology have all radically evolved..

Connections to home

Some immigrants leave their homeland and can never return. Others have the means and desire and can make return trips to their home nations. Connections to countries of origin remain strong but many families are split between countries. One of the benefits of naturalization is they receive a United States passport and do not risk the loss of residency if they travel.

Some return to help or bring family here. For example, Liliya Mayevsky and her family have been very active in humanitarian efforts in her native Ukraine since the war began. Her American-born nephew and her brother have made trips to the country to deliver relief aid since the war broke out.

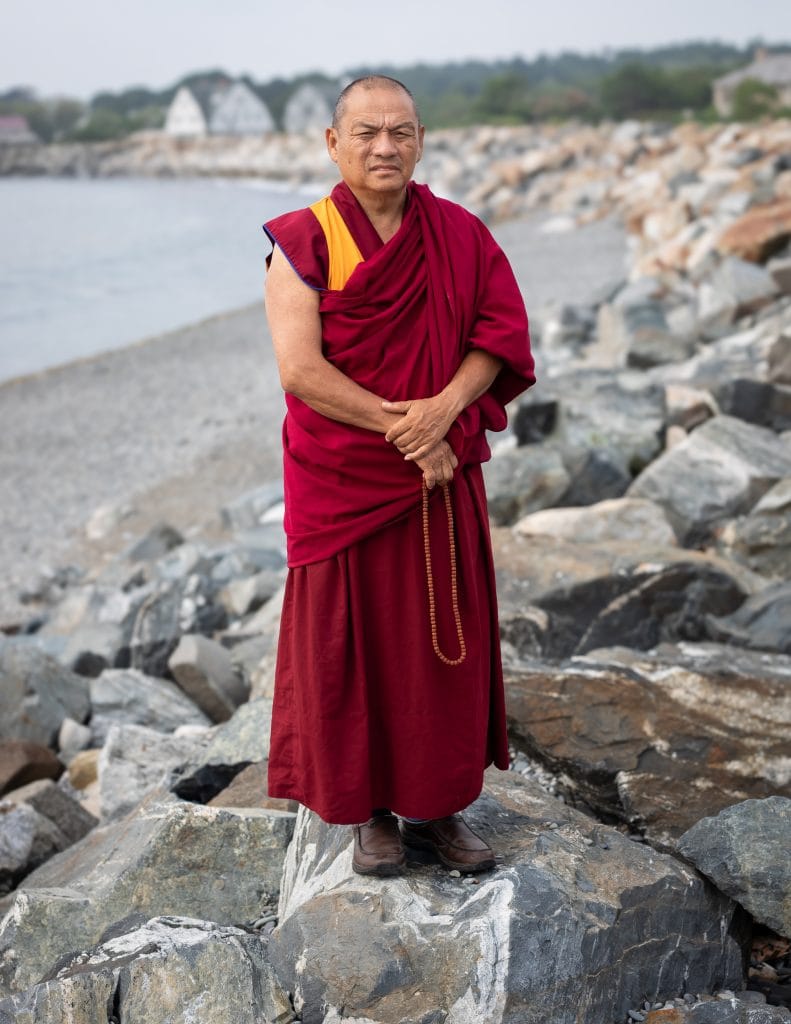

Geshe Gendun Gyatso is a Tibetan Buddhist monk who is now a naturalized citizen. Each winter he returns to the resettlement community where he was raised in southern India. He reconnects with his family and continues his religious studies at his home monastery. “I like to be close with my monastery. So, that’s why I go back and forth every year, four months, five months, I go back to associate with the monastery,” he said.

Immigrants also have a significant economic impact on their home countries. Data on the volume of financial remittances sent to native countries is difficult to determine. According to the United Nations on average migrants send $200 to $300 home every one or two months. On average this equals less than 15% of their total earnings. 85% of their earnings remain to cycle through the US economy.

Making it in America

It is a rare individual that rises above their native circumstance and makes it to our shores. Getting to America is a long shot and is a significant accomplishment achieved by few.

Getting here is half the battle. That is only the beginning. The next challenge is making your way into American society. For many immigrants basic survival is daunting and thriving here is an enormous challenge for newcomers.

America is great but hardly easy, particularly for new immigrants. Adaptation and assimilation are difficult. Social and economic barriers can be hard enough for native-born Americans and navigating them can be daunting for immigrants. For some, it is impossible.

Housing, employment, and transportation are all impacted by residency status. Cultural differences, language, and education greatly affect success.

For some, the lack of familiarity is overwhelming and a source of anxiety and ultimately negative mental health outcomes. One recent refugee from Afghanistan who has been resettled in Manchester – and requested his name not be used in this story out of fear of retribution from the Taliban on his family members who remain in Afghanistan – said, “I miss everything – my home, the rest of my family, the food, my city, my professional work, everything is different here, I am so lost.”

For Ali Sekou from Niger, his first encounters with snow and winter sum up the adaptation challenge nicely.

“I will tell you, the weather was a shock because I even got frostbite, so I was playing outside in the snow with kids because you have that energy, you are excited, and you see something that is beautiful. Snow is beautiful, no doubt. But you learn quickly to adapt. When the people that you live with tell you no. When you are there, you wear gloves. When you are here, you do this.”

Speaking about the adaptive power of immigrants he said, “The entire learning process, it’s just fascinating. And I think everybody should be inspired by it because as humans, it’s not easy to adapt to even the place you were born. Imagine a place that is thousands of miles from the place you were born. So I listed all those things that were a challenge, and the weather was part of it,” Sekou said.

For some, language is an issue, especially with immigrants who arrive later in life. Many immigrant households rely on their children who get English as a Second Language (ESL) in school to serve as family translators. The language barrier can lead to isolation and is a major factor in successful assimilation. English language skills change employment opportunities.

One oft-repeated story was that English was taught in the refugee camps and they picked it up during the multiple years spent there before coming to the United States. For some, English is taught in their home country schools. Nurses from the Philippines are all fluent which gives them an edge in the job hunt. “The medium of instruction in the schools, in any of the schools in the Philippines was in English. All the books are in English,” said Glory Wabi.

Qualifications, certifications, and professional experience may not transfer well from countries of origin. Immigrants with professional accreditations and jobs arrive here to find that they are not easily recognized or transferable to employers.

Kenyan Caroline Oguda, who is a professional healthcare worker, said, “The unfortunate thing is, this country does not accept other countries’ qualifications. You have to go through hoops to translate, like, your degrees to the American degree. A lot of people can’t afford it, and that’s not common knowledge. So what ends up happening is they end up being people who are housekeepers and all, and then they end up on the system. Not because they want to, and it’s a big shame to them. Because the qualifications weren’t accepted.”

Obstacles to credentials transferring are an important part of policy discussion. This is even more critical when it comes to our healthcare system. Immigrant-origin adults make up 16.2% of the healthcare sector of our economy workforce; 25.5% of physicians and surgeons; 16% of registered nurses; and 23.1% of healthcare support workers are foreign-born.

New Hampshire has an aging population with 20.7% of the state’s population over 65 and decreasing access to healthcare in rural areas. This aging population increases the demand for healthcare workers in an industry that already relies heavily on foreign-born labor. Future restrictions on immigration and potential deportations will negatively change healthcare services, especially in the Granite State.

Sebastian Fuentes lived and worked as a non-English speaking brown-skinned person in the Northern woods of New Hampshire. His experience with prejudice was a mixed bag. He politely describes those experiences this way: “I think it’s a little bit of everything, you know? I found really welcoming people, really gracious people, but I also found a little bit of like, you know, the typical people that are not, I don’t want to disrespect them, but ignorant to other cultures, other religions, other faiths. So I found some of that, but I will say that most of my experience was a welcoming one, one where I was able to be myself, and one where I felt like people would listen to my voice regardless of where I was coming from. But I think that has to do a little bit with my personality. I’m a go-getter.”

Lochan Sharma is a Nepalese immigrant who speaks about his experience this way: “I’ve been very fortunate that everywhere I’ve gone has been, like, hasn’t been too, you know, too racial. It’s been very open, and everywhere I’ve gone has been, like, had communities where I could fit in, but I also haven’t had trouble fitting in otherwise into very just white spaces. I’ve been very fortunate in that regard.”

Some of the African immigrant community have experienced what they consider a pattern of police harassment and abuse that they perceive is due to their origin and skin color. “ You know, they put you on the radar, and then when you go somewhere, the police will stop you, they’ll follow you,” said Ekoue Abroussa.

Seeking refuge when home is no longer safe

As the security situation in Haiti deteriorated Patrica and her husband feared for their lives and they fled Haiti with their two children ages 3 and 8.

“We left Haiti because of the bandits, we left Haiti because of insecurity, with my two children and their papa. We went through Nicaragua. We went through Honduras and Guatemala. We arrived in Mexico three months later, and then we came to the United States, we crossed the border until finally arriving in the United States.”

Because they entered the country without permission they are undocumented immigrants; there is currently no process in place in the U.S. to change their status.

Patricia has advanced degrees and was working as an agricultural researcher in Haiti. They came to New Hampshire because they had some family members living in the state. Now they are scraping by with church support and under-the-table odd jobs. The desire to work is great but the lack of status is challenging.

Reflections on Being an Immigrant

Immigrants face multiple challenges and issues navigating a new country and making their way into New Hampshire society. Although some of their experience has been negative, most have expressed tremendously positive views on being here. Some have gripes, but in general, these folks are not complainers.

The most often described feeling and attitude is of profound gratitude. Those interviewed expressed a desire to move forward, to become and remain productive citizens, and to be regarded as vital to their communities. Some had complaints but all understood the good fortune they have gained by being here.

They embrace the notion of the “American Dream” wholeheartedly. They have faith that they have a chance for a better future here. They may need a hand to get started but all professed a desire to be independent and to hold their own.

One African immigrant described his community this way: “ The people, they are refugees. They are looking for jobs. They are working. That’s why they’re coming. They’re good people.”

Glory Wabi, who has been here in New Hampshire for decades, speaks of the mutual benefit of immigration. “The thing is, we can learn from each other. You know, we can learn your culture, you can learn from our culture, and together we can just make this world even more beautiful. Just working together.”

Ali Sekou is from Niger and is now a citizen and Concord city councilor. He reflected on his immigration path and the value of America’s “melting pot” saying, “It’s great. I think that’s what made America the great nation it is. Because you prove yourself, you follow the law, you get where you want to be. And many people around the world and many Americans believe in that, which is why the country still holds together because of that belief. And it’s a blessing.”

Tibetan-American Geshe Gendun Gyatso offers this advice to non-immigrant, native-born Americans for dealing with the immigrants they encounter in New Hampshire

“It is best to be non-judgemental. A lot of immigrants, they struggle in their own country, with political issues, and financial issues, and so on. If they follow the rules and regulations, then they should be welcome and we should just support each other and we should treat all human beings as human beings, As Americans say, you should treat others how you like to be treated yourself. So it’s kind of like that; it’s all equal, everybody deserves to be happy, to live peacefully and treated non-judgmentally.”

The specter of mass deportations being closer to reality next year hangs over the country. Many of the immigrants we interviewed say they are intimidated by the rhetoric and terrified by the implications of that policy.

Maria Elana Letona is a native of El Salvador who has been in the U.S. since the 1970s. She was a director of an immigrant rights group and offered this insight about deportation.

“I just think that a contradiction lives within us. On the one hand, we find it very difficult to believe that the land of promise, the land of dreams, could do this. That on the one hand, we can’t really quite believe it. On the other, we do worry and live with a kind of anxiety. But the truth is that the anxiety is already there because we have never known when we are going to be deported. Because deportation has been part of our experience as an immigrant community for decades, maybe longer,” Letona said.

“I think that what I want to speak to, in terms of that narrative, I personally, – so I’m a naturalized U.S. citizen. They’re going to start with undocumented immigrants. They’re going to move down the line. And at some point, they’re going to get me.”

Based on her own experiences, she’s cautious about the consequences of deportation on the future of this country.

“I think that what I worry the most is about what is going to happen to this nation. What is going to happen to the people who have been so welcoming to me, so warm to me, so open-hearted to me, right? I don’t know that people are realizing that something like this happened in Nazi Germany. And I understand that there are people who don’t believe that such a thing happened.

I happen to believe that that was the case. I grew up knowing about it because it’s in the history books. And I think it would be very good for all of us to actually dig deeper about what that means. Because when they start dehumanizing people, there’s no end to it, right?”

This project was made possible in partnership with Granite State News Collaborative and generous support from the Eppes-Jefferson Foundation, and was produced by Dan Splaine for Ink Link News, a founding member of Granite State News Collaborative.