Equal Pay Day 2025: Wage gap in NH and U.S. is widening

The wage gap hurts women’s ability to save for retirement and reduces their total Social Security and pension benefits, making older women more likely to live in poverty. In the past two years, there have been efforts on a national scale to close the gap, including the Paycheck Fairness Act, which s

MANCHESTER, NH – Tuesday is Equal Pay Day 2025, the day nationally that women’s pay catches up with what men made the previous calendar year. Nationally, women make 83 cents compared to the male dollar, which is down from last year when Equal Pay Day was March 12.

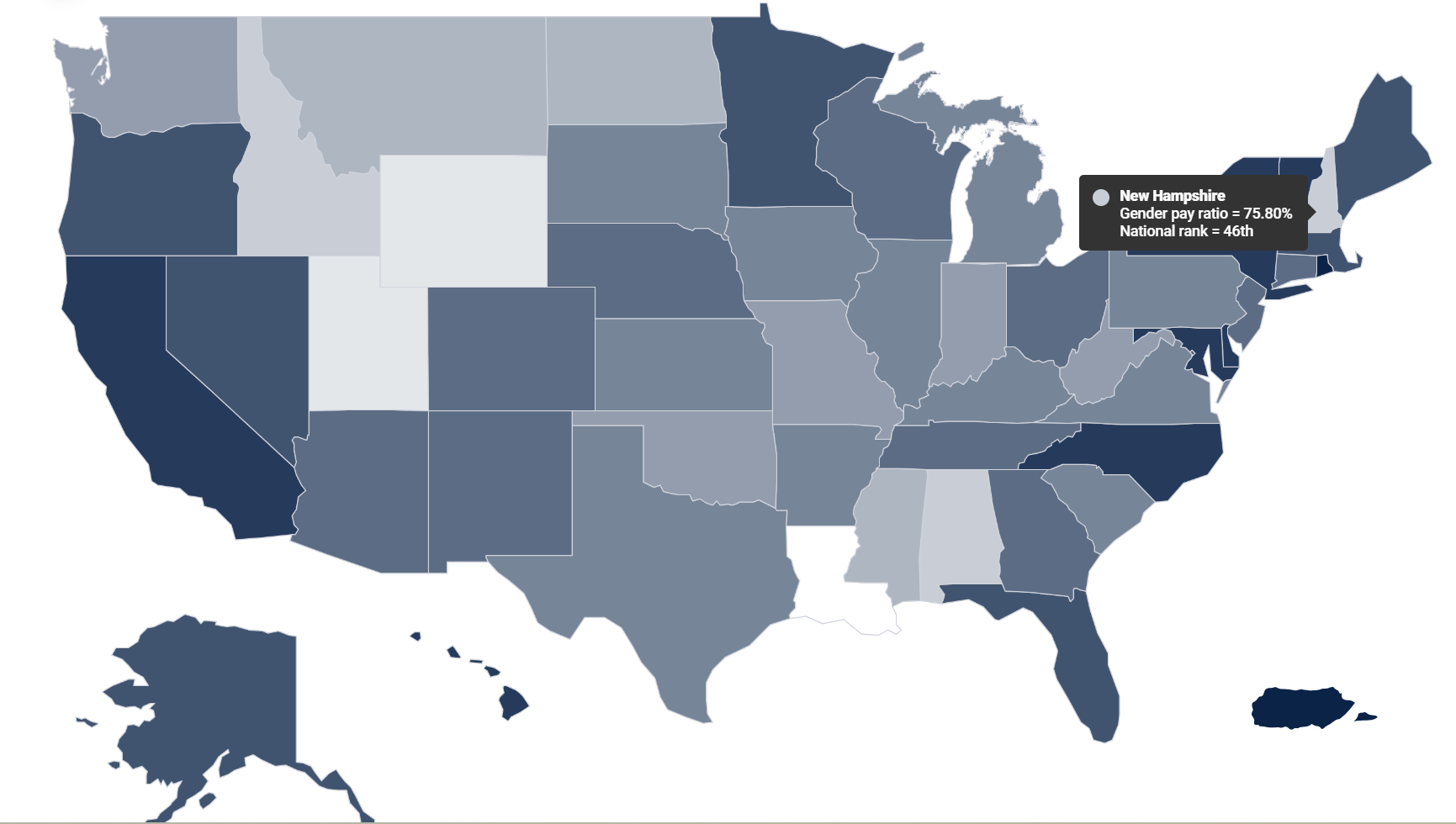

In New Hampshire, the gap is much wider – women make 75.8% of what men do, 46th among the 50 states and Washington, D.C., according to the most recent U.S Census Bureau numbers.

Equal Pay Day was determined by the National Committee for Pay Equality, which is a way to bring attention to the gender pay gap. The organization has set Equal Pay Day every year since 1996. It determined in December that March 25 was 2025’s Equal Pay Day, then the NCPE, which had been in existence since 1976, dissolved on Dec. 31.

The 2026 Equal Pay Day will likely be later in the year, the gap wider.

National legislation and programs to close the gap have been done away with under the Trump administration. Locally, state legislation that calls for pay transparency and a higher minimum wage – two proven measures to help close the gap – isn’t likely to be successful if history and the current political climate are any indication.

Equal Pay Day is even later in the year when it’s calculated for Black women alone, who are paid 63 cents compared to the male dollar. Latina women are paid 55 cents. Women with children, those who are disabled, and LGBTQ+ workers also have much later Equal Pay Days. Native American women don’t mark Equal Pay Day this year until Nov. 18.

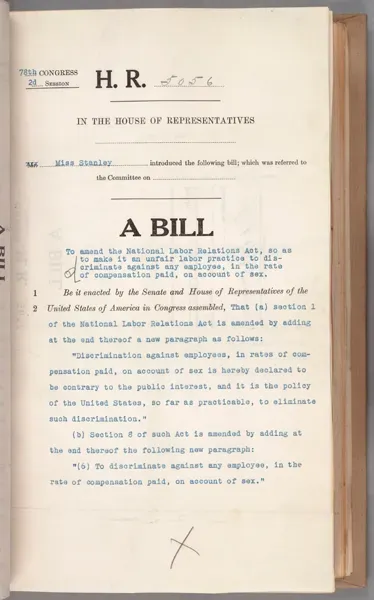

The wage gap hurts women’s ability to save for retirement and reduces their total Social Security and pension benefits, making older women more likely to live in poverty. In the past two years, there have been efforts on a national scale to close the gap, including the Paycheck Fairness Act, which seeks to strengthen the Equal Pay Act of 1963, by making it easier for workers to challenge employers on the basis of pay discrimination. It has passed by the U.S. House many times since it was first introduced in 1997 (and every legislative session since), but has not passed the Senate, most recently last year. With the current political climate, which includes ridding the rolls of any legislation or policy that protects women, minorities and the disabled from discrimination, it’s unlikely that legislation will be successful, or that the gap will close in the coming years.

Two years ago on Equal Pay Day, acting U.S. Secretary of Labor Julie Su announced several federal initiatives to close the gender wage cap, particularly for populations that are traditionally left out. All of the initiatives she announced have been done away with by the current administration. These include:

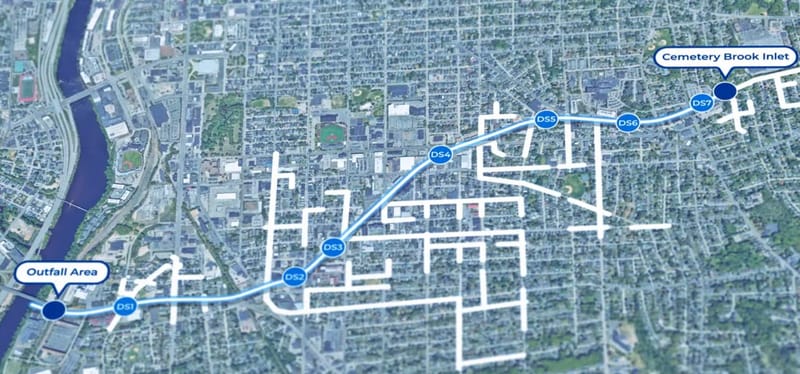

- The Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs policy to remove construction industry hiring barriers and promote diversity in hiring qualified workers;

- The Employment and Training Administration’s support of TradesFutures, a strategy that was developed by the National Urban League and its community partners to substantially increase the number of participants from underrepresented populations – including women and underserved communities – in registered apprenticeships in the construction industry;

- The Good Jobs Initiative, which provides tools with practical strategies to increase equal employment opportunities on infrastructure projects, including using Project Labor Agreements as Tools for Equity and establishing Access and Opportunity Committees, stakeholder groups that meet regularly to monitor and support diversity and equity goals on a specific project.

The U.S. Department of Labor Women’s Bureau last year did a more in-depth analysis of data than in the past, and found about a third of the gap in wages between men who work full-time, year-round and women who do the same can be explained by worker characteristics, such as age, education, industry, occupation, or work hours.

“However, roughly 70 percent cannot be attributed to measurable differences between workers,” the report said. “At least some of this unexplained portion of the wage gap is the result of discrimination, which is difficult to fully capture in a statistical model.”

A report based on the analysis says that efforts to close the gender and racial wage gap should address the leading contributors to differences in pay. That means addressing occupational and industry segregation, as well as “discrimination and other factors not easily captured in statistical models.”

The report concludes, “This will require supporting women entering male-dominated fields, raising wages and job quality across all sectors and especially in women-dominated jobs, and ensuring racial and gender equity in the high growth fields creating the jobs of the future.”

The U.S. Census Bureau and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics in years past have published Equal Pay Day information, but this year they did not.

Even though the NCPE, which determined when Equal Pay Day would be marked, no longer exists, a variety of surveys also do the work. Payscale, a company that specializes in compensation data and software, used data and a survey to determine that women overall made 83% of what men made on a dollar last year. The Pew Research Center came up with 85%. Other groups, including Equal Pay Today and the American Association of University Women also publish information about the gender pay gap.

NH’s pay gap

New Hampshire’s gap has been widening, according to Payscale. Payscale releases a Gender Pay Gap Report every year before Equal Pay Day.

The fact New Hampshire’s gap is widening is despite a state law that requires companies to pay women and men with the same qualifications the same wage.

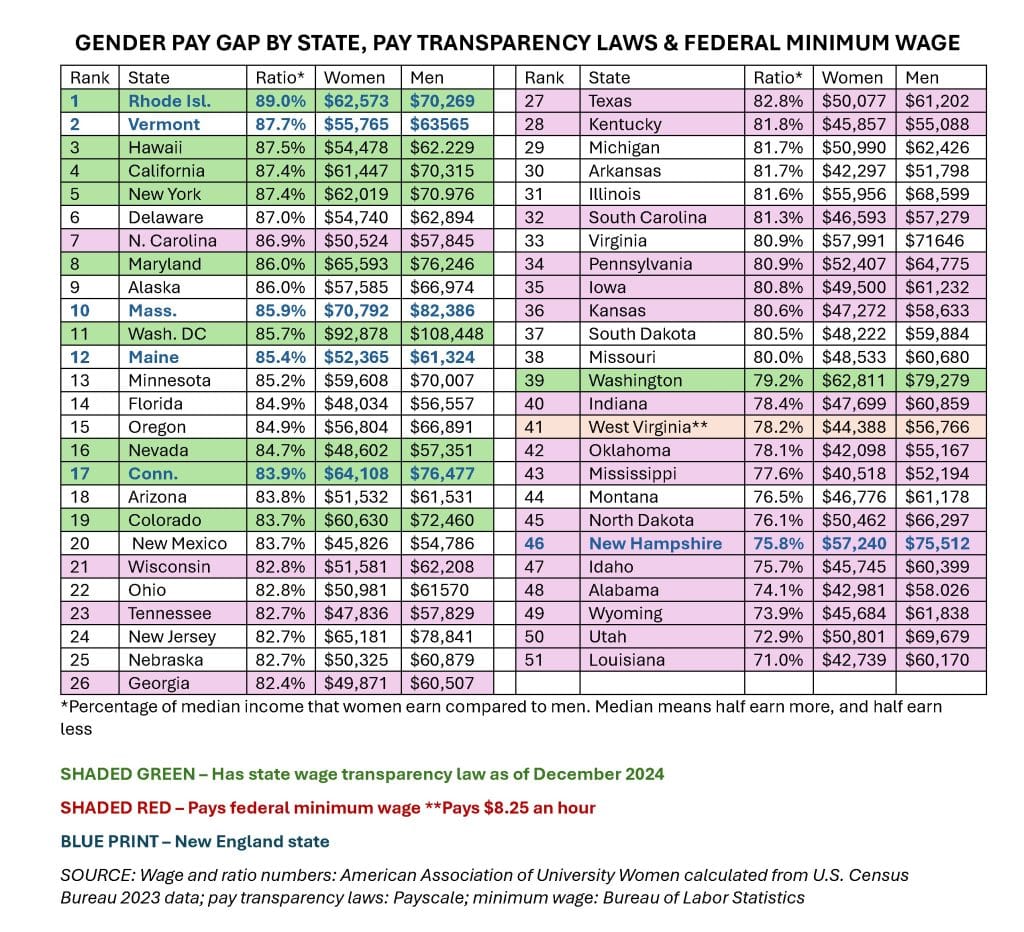

Payscale’s report says the reasons for the wage gap nationally are many, but their statistics show that states that have passed pay transparency laws that require companies to make what it pays public have closed the gap.

New Hampshire doesn’t have such a law. It also pays the federal minimum wage of $7.25, as do all the states in the bottom 10 of the gender pay gap ranks (using 2023 numbers), and 14 out of the bottom 20. Only one state that pays the federal minimum wage, North Carolina, is in the top 20 in closing the gender wage gap.

Last week, the New Hampshire House shot down a bill that would raise the minimum wage to $15 by 2028. It’s the 12th year in a row the Legislature has killed a bill that would raise the state’s minimum wage. The federal wage hasn’t increased since 2009.

The Pay Fairness Act also calls for pay transparency, something that is picking up steam among states. Five of the 10 states that had pay transparency laws in effect before 2024 were in the top 10 of closing the gap last year, and nine are in the top 20. New Hampshire also doesn’t have a pay transparency law, which makes its law that qualified workers must be paid the same, regardless of gender or race.

Wage transparency is essential to closing the gender gap, Tanna Clewes, CEO of the New Hampshire Women’s Foundation, told Manchester InkLink.

“It continues to be a challenge to access reliable and complete data by gender in New Hampshire,” Clews said in a 2022 article. “To address a challenge, we must first understand it and be able to measure it. Transparency in wage data is key.”

She said that business owners and leaders can commit to equal pay by publishing data that shows progress. Workplace policies that are flexible and “address the outsized family responsibilities that women often shoulder” are also key.

Gender wage gap myths

The Institute of Women’s Policy Research says that the gender pay gap “is an accurate measure of the inequality in earnings between women and men who work full-time, year-round in the labor market and reflects a number of different factors: discrimination in pay, recruitment, job assignment, and promotion; lower earnings in occupations mainly done by women.”

It also agrees that “women’s disproportionate share of time spent on family care” plays into the numbers, because mothers still tend to be the ones to take more time off work when families have children. Women often work jobs that traditionally pay lower wages, and other factors aside from discrimination play a role. But research over the years from many sources is consistent in that discrimination also plays a large role.

The IWPR says that the wage gap is often rationalized by the “choices” women make, but those choices may also be limited by discrimination.

“‘Choice’ is an unverified assumption,” the policy report says. “There is considerable evidence of barriers to free choice of occupations, ranging from lack of unbiased information about job prospects to actual harassment and discrimination in male-dominated jobs.”

It gives the example of a library assistant, who may choose to go to school for six more years to become a librarian. On the other hand, she may choose to go to school for half that time and become an IT support specialist if she knew that librarians and IT support specialists were paid roughly the same.

“In a world where half of IT support specialists were women and half of librarians were men, men and women might ‘choose’ very differently than they do now (where IT is a male-dominated field and librarians are female-deominated),” the IWPR says. “We do know that young women and men generally express the same range of desires regarding their future careers in terms of such values as making money and having autonomy and flexibility at work, as well as time to spend with family.”

Clews said New Hampshire residents who want to close the gender wage gap in the state should contact their representatives. “Encourage them to support policies that support working women: accessible and affordable child care, a livable minimum wage, paid leave, affordable housing, access to health care and a full range of reproductive and sexual health care choices all impact a women’s ability to determine her own economic future,” she said.