End-of-life doulas can help ease the most challenging of life’s transitions

End-of-life doulas and pregnancy and infant loss (PAIL) advocates can comfort the dying and support the grieving while adding meaning to the experience of loss.

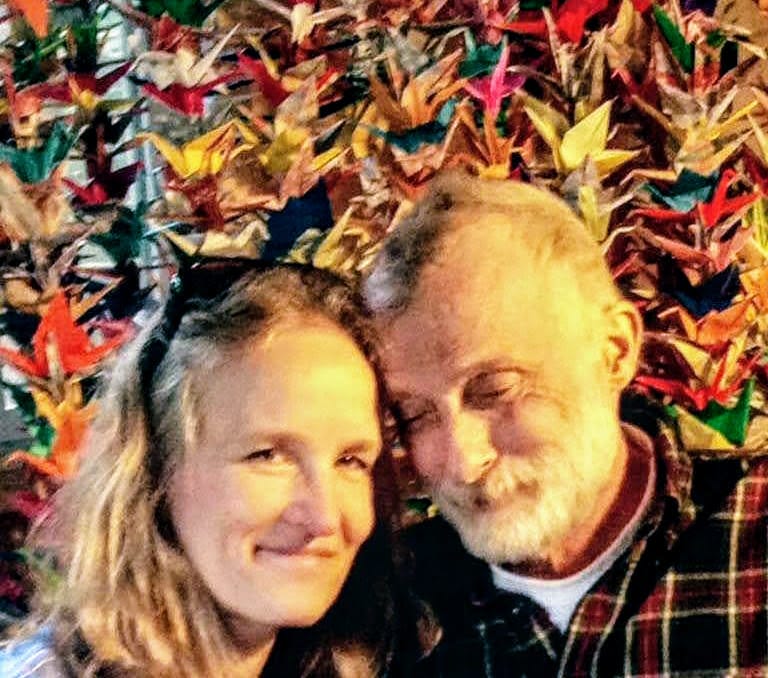

Jackie Davis of Temple says a death doula guided her through some of her darkest days.

Davis contacted New England-based Threshold Care service providers as her husband, Rick, 64, lay dying from glioblastoma, an aggressive brain cancer.

“That was not in the plan,” she says of her husband’s illness.

After his diagnosis, Davis struggled with emotions like anger, sadness, and helplessness. She says naturally, when the end is near, everyone’s attention turns to the dying person. But the one who would normally be there for her in her time of emotional need — Rick — couldn’t.

“I was so busy trying to keep things going, and get him to the doctors and get the medicines and cook the meals and call his friends to come and visit him. He would be the person, my partner, my buddy, taking care of me,” says Davis.

That’s when fate intervened and Davis learned about Threshold Care. One of her friends, Deana Darby, is an end-of-life doula with the company. Davis used Darby’s services during Rick’s final days, calling her work “human care.”

Davis learned that end-of-life doulas, who are trained to handle these delicate situations, possess an understanding even close friends might not grasp.

“Do you know how to be around somebody whose husband is dying? Like, do you know what to say?” says Davis.

She says friends would want to “fix” the problem, because it’s difficult to see another friend in pain.

“They don’t like seeing you sleepless, or weeping, or angry, or whatever it is that you’re going through,” Davis says.

Spectrum of Services

End-of-life doulas and pregnancy and infant loss (PAIL) advocates can comfort the dying and support the grieving while adding meaning to the experience of loss.

Holistic Birth & Beyond in Manchester offers various doula services that can be tailored to a person’s individual needs.

Kizzy Bailey, owner of Devoted Doula, is a PAIL advocate, birth doula, patient educator, postpartum doula and lactation educator with Holistic Birth & Beyond. PAIL advocates provide emotional support for women who seek abortion or are going through a miscarriage, stillbirth, or other traumatic event.

Bailey says part of her job is to empathize as well as educate.

“Knowing that you’re carrying a child that is no longer living is hard. And a lot of people don’t realize what’s happening inside their body,” says Bailey.

For those interested in her services, Bailey will suggest a “care package” that can include coping tools like writing in a journal, using aromatherapy, or learning how to ease cramps. Bailey can escort a woman to an abortion clinic, or offer information for a therapist.

Bailey says when couples want to memorialize their baby’s life, there are more choices, and parents have more time than they realize.

For example, ice packs can preserve the body a bit longer, so grieving parents can spend additional time with the baby. They can dress or bathe the baby, name the baby, gather footprints and handprints, or do other meaningful things.

She says if the mom loses the baby unexpectedly, they can still gather the remains for a burial, if they wish, by lining the toilet with cheesecloth.

“They can spend a lot of time, sometimes days, at the hospital with their baby even though it’s not alive. It all sounds scary and like, ‘who would want to do that’? But a lot of people don’t realize that they would have wanted to until after it’s too late,” Bailey says.

She says doulas understand the connection between mother and baby, and that even if a birth isn’t carried to full term, “it’s still part of you.”

“Sometimes people just need a hand held and someone to tell them that it’s okay. It’s okay to look at your baby, it’s okay to take pictures of your baby,” says Bailey, who adds that she’s not there to influence the woman toward any one choice.

“What you’re feeling is what you’re supposed to be feeling, and having somebody tell you that’s okay, to feel that way, is what’s important,” she says.

Bailey can also help a mom cope with miscarriage and the accompanying fear of delivering a baby who has died, so that she’s better prepared to handle the impending flood of emotions.

“Once they have that baby in their arms, it kind of changes everything. It’s just getting to that point,” she says.

If the parents don’t want to memorialize the baby, that’s okay too.

“Some people can lose a baby after two months and be like, ‘you know, whatever, it’s fine.’ Then other people can be completely devastated,” she says.

Sandy LaFleur of Wilton, a green burial advocate, is also an end-of-life doula with Threshold Care.

She says historically, doula support was often done by females in the community. The role differs from hospice services, when health care workers supply medications to keep the person comfortable.

LaFleur says doulas understand the process of death but don’t medically intervene. Instead, they coordinate various supports to take some burden off overwhelmed caregivers while offering a holistic approach to a person’s final days and hours.

“We’re companioning people at the end of their lives,” LaFLeur says.

To help a client, LaFleur might conduct a “life review,” and ask people what’s important to them, what they want to have happen to their body and how they want to be celebrated. Then she delivers these wishes to the dying and the family members.

For example, LaFleur can sit with the dying person when someone needs to grab an hour of sleep or greet visitors. This way, the person won’t be alone.

“The family can spend the meaningful time with their loved one who’s passing rather than having to deal with the minutiae,” LaFleur says.

Doulas also help the dying person realize their last wishes and requests, which could mean anything from bringing in the person’s favorite flowers, or playing sounds from the beach, because it’s something they’ve enjoyed. For example, LaFleur, who is also a musician who plays the Appalachian dulcimer, can arrange music for the funeral service, or play music at someone’s bedside.

Lee Webster is a funeral reform advocate and executive director of New Hampshire Funeral Resources & Education, an organization that helps families understand their options when caring for their loved one before and after their death.

Webster agrees doulas can provide comfort and aid the grieving while their loved one is in their final days, such as help cook meals, clean up, and take care of other household tasks. Doulas can be paid for these tasks, but may perform them for a longer period of time than a hospice volunteer would.

But once the person dies, a doula’s role automatically changes. Other regulations take effect, and a doula can no longer charge for services. They become volunteers.

“Before death, we’re working with the family. We can charge for our time. But after the death occurs, we (doulas) are there to educate,” says Webster.

Once the person dies, there’s no longer a need for medical care of any kind.

“We’re talking about non-medical care, support for the family and the dying. You can educate people about those things, but you’re doing it as a volunteer,” she says.

Contrast that with the funeral home industry, which charges for things like viewing, transport, burial, embalming and the casket. Webster says at New Hampshire Funeral Resources, Education & Advocacy, “We’re educating and empowering families to do this themselves.”

Webster says when considering finding an end-of-life doula, it’s important to understand New Hampshire state rules and regulations. In New Hampshire, at least, residents can do a lot of things funeral homes do – they just do it on their own.

“Here in New Hampshire, and every state in the country, people can continue to care for their own dead. They can bathe them and shroud them, dress them, cool them, keep them in their own home, or another location that’s private,” says Webster.

New Hampshire residents can also take care of paperwork, such as obtaining a burial transit permit, all without hiring a funeral director. Not every state allows this.

“The key is understanding the difference,” says Webster.

‘We had had a good death’

Davis says doulas can recognize hidden signs of stress that others might miss, and will reach out when needed.

“Having somebody who gets it, who understands if you need space, or who sees you slam pots and pans in the kitchen and invites you for a walk, because actually, it’s not about the pots and pans in the kitchen. It’s about your whole life turning inside out,” Davis says.

While hospice nurses assisted with Rick’s physical and medical care like toileting and showering, Davis says they were “there for a different purpose.”

Darby provided Rick with simple companionship.

“Sometimes Deana would just sit next to him. She would maybe speak to him or pat his arm, just witness and be present with him,” says Davis, who likened a doula to a conductor.

While other friends stayed with Rick at their home, talked to him, read him poetry, or played him some music, Darby was also present, sleeping there when she knew death was imminent.

“For me, the person left behind, it was comforting to have people in the house,” Davis says.

Doulas can help people decide what kind of burial the dying person wants and the costs, and can remain non-denominational.

Rick died at home Sept. 7, 2015, about 11 months after his diagnosis. Davis’ need for a doula’s support continued after his death.

“There was nobody sitting down with me, except for the doula, to say ‘So cremation or burial, what is it going to be? What are his wishes? What are your wishes?’ ”

Davis says Rick had requested a three-day vigil, and Darby organized a “yarn” ceremony for Rick’s memorial to provide additional meaning to his legacy.

As people shared a memory about Rick, they wrapped a section of yarn around their wrist, then passed the ball to the next person, who did the same. After Davis voiced the last message, the yarn was cut; the rest stayed with Rick, who was later cremated.

Davis said she kept that yarn on her wrist for weeks.

“I wore that yarn until it fell off my wrist. It was a couple of months before it just wore away.”

She says the yarn ceremony was extremely meaningful. Eventually, she found some normalcy in her life.

“The sun came up every day. Even though he wasn’t here …. that was possible,” she says.

While having a death doula can’t remove the grief, Davis felt things were done right.

“We had had a good death. We had community. We had connection; we had honored Rick.”

Davis says taking time to process Rick’s death was a gift, “something that’s exceedingly rare these days.”

“When my grandmother died, the guys came and put her in a zippered bag and took her away. That was it. With Rick, there was no rush, it was timed well,” says Davis.

LaFleur suggests discussing your wishes when you’re healthy.

“The time to think about what you want in your death is not when you’re in hospice, it’s when you’re fully alive and able to affect change. It’s unhealthy not to talk about them,” LaFleur says.

Davis agrees it can be a necessary and important conversation.

“If it’s you that goes first, what do you want to have happen? Just write it down, put it in a folder. And then make sure anyone that needs to know about it knows where that folder is. Anything you can do, honestly, is helpful to the person left behind,” says Davis.

“Becoming comfortable talking about end of life and what’s important actually makes your living all the more precious,” LaFleur adds.

Above: Jan. 2019 podcast by hospice and oncology nurse Suzanne B. O’Brien with guest Lee Webster.