Anatomy of a cold case, solved: How Portsmouth police tracked down Laura Kempton’s killer

Here’s how it all happened, based on the 25-page report that accompanied Thursday’s news conference, as well as past newspaper accounts.

PORTSMOUTH, NH – When announcing Thursday that the 1981 Portsmouth homicide of Laura Kempton has been solved, Attorney General John Formella said that, despite ups and downs and difficulties in investigating the case, the Portsmouth Police Department and state Office of the Attorney General never gave up.

The investigation ultimately led to Ronney James Lee, who was on Portsmouth police radar in 1982 and 1983 for burglaries and sexual assault, but never on their radar for the murders until criminal investigations and science caught up with each other.

Formella said that he hopes the resolution of the case will send a message “to anyone who has been affected by a cold case in this state that we will never stop working these cases, we will never forget about these victims, and we will never stop looking for new leads, new technologies, new opportunities to solve these cases.”

The more than 40 years it took to find Kempton’s killer is a long road of both old-fashioned police work and new science and investigative techniques that weren’t even a blip on law enforcement radar when she was killed.

“Cold Case homicides are some of the most complicated and difficult that any investigator can take on,” Assistant Attorney General Scott Chase, head of the cold case unit, said at Thursday’s news conference.

Here’s how it all happened, based on the 25-page report that accompanied Thursday’s news conference, as well as past newspaper accounts:

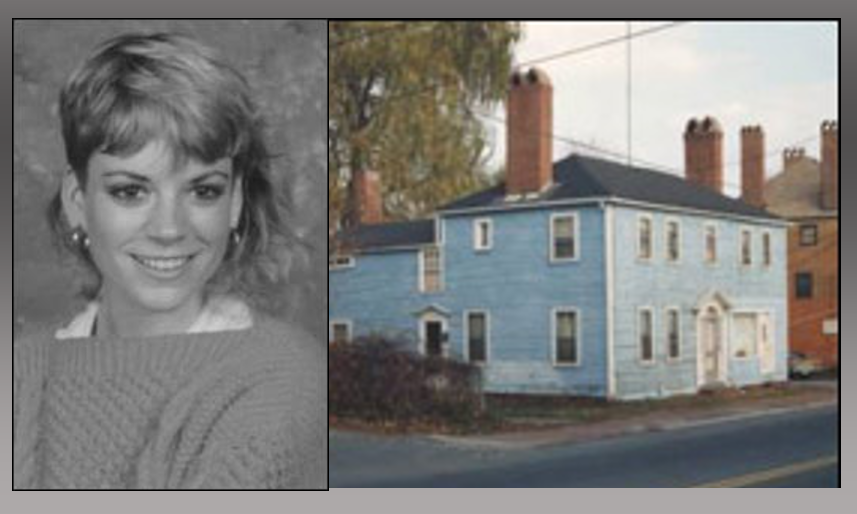

Sept. 27, 1981. Laura Kempton had just started working at Macro Polo, a gift store on Market Street. Her friends said she was an outgoing free spirit with a big personality and a love for new-wave fashion. She didn’t have a boyfriend, but enjoyed socializing and dating.

The night before, a man she was dating spent the night. He told police later that he noticed that Kempton was careful to lock her door, even when they went out briefly at 2 a.m. to get food. She also checked to make sure it was locked before they went to bed.

The morning of Sept. 27, a Sunday, Laura put cash in an envelope and left it on the kitchen table. The pair went to Goldie’s Deli for breakfast, and then Laura went to work at Marco Polo, a shift that ended at 7 p.m.

Later that night, she and a friend went to Luka’s restaurant, where a live band was playing, for dinner, drinks and dancing. They left between 1 and 1:30 a.m.

They walked to Laura’s apartment at 20 Chapel St., and Laura invited the friend to stay, but she said she couldn’t because she had to get up for work the next morning, which was a Monday. The last time she saw Laura was outside the door to her apartment.

Sept. 28, 1981. At 9:25 a.m., Portsmouth police Officer Ron Grivois arrived at Laura’s apartment to serve a summons for parking violations. In the hallway of the apartment house, he saw that one of the panels to the door of Laura’s apartment was missing, and through the opening he saw a body on the floor, partially covered with a blanket, but with two legs, bound with a cord, visible. There appeared to be blood on the wall.

Detectives found that all the windows and doors were locked, but that they could reach through the hole in the front door and unlock it from inside.

Laura was covered from the knees up with sheets, bedding, her mattress and box spring. Her ankles were tied with a white electrical cord from an electric blanket and there was a telephone cord around her neck. There were signs of blunt force trauma to Laura’s head and face, and a large amount of blood both on the floor and on the wall.

There appeared to have been a struggle, and the small apartment was ransacked. Later, when Laura’s date from Saturday night and Sunday morning told police about the envelope of money on the table, they looked, but couldn’t find it.

A resident of the apartment building told police later that he’d noticed early on the morning of Sept. 28 that the hallway light was off, and when he went to take out the bulb to put in a new one, found it had just been loosened by someone.

Investigators seized hundreds of items that could potentially be evidence, including the two cords, a pillowcase that covered her head and neck and a cigarette butt and a glass wine bottle, both found on the floor next to her body.

They processed both the inside and outside of the apartment for finger and palm prints, and found several, including on the door to the apartment and on a telephone in the apartment.

Neighbors in the apartment building said Laura’s door had not been broken before that morning. Investigators determined that whoever killed her had broken the door with the mailbox from the hallway – a piece of it was found inside the door. There were pry marks on the outside of the broken door panel that matched a piece of the metal mailbox found inside the apartment.

Later on Sept. 28, Dr. Dennis Carlson, a certified pathologist with Exeter Hospital, performed the autopsy at Woods Funeral Home. The state hadn’t yet established the Office of the Medical Examiner and they relied on local pathologists to do the autopsies when there was a suspicious death.

Carlson determined cause of death was “a severe beating about the head” with a finding of terminal pulmonary edema, which is fluid in the lungs. The head injury included massive trauma to the left side, with lacerations, extensive complex scull fracture and brain contusions. All of that was consistent with her being struck with a heavy blunt object, possibly the wine bottle found next to her body. He said she was also beaten with a fist.

He determined the time of death to be around 2:30 a.m., plus or minus an hour. [When Chief Medical Examiner Dr. Jennie Duval reviewed Carlson’s autopsy report in March of this year, she noted that today’s standards wouldn’t support pinpointing a time of death that specifically, but she said the autopsy findings are consistent with death in the early morning hours of Sept. 28, 1981.]

Samples Carlson took from the body included vaginal swabs and smears, and skin scrapings from her upper thigh. These items were sent by the Portsmouth Police Department to the New Hampshire State Forensic Lab for testing.

This was four years before a scientist in England worked out how DNA testing could be used in criminal investigation, and a decade before New Hampshire first used DNA in a criminal investigation. Before DNA’s use in crime investigation, swabs could sometimes reveal the blood type of a perpetrator.

These swabs would turn out to be crucial to solving the case 40 years later.

The lab determined the blood on the wine bottle was Type A, the same as Laura’s, confirming it was likely the murder weapon. Type A blood was also found on the door molding that had been underneath Laura’s body and the pillowcase that was over her head.

The telephone cord that was found wrapped loosely around her neck tested positive for two chemicals that are found in seminal fluid. They also found sperm in the vaginal smears and skin scrapings.

Oct. 19, 1982. Tammy Little was found murdered in her apartment at 315 Maplewood Ave. in Portsmouth. Little, 20, like Laura Kempton, was a student at Portsmouth Beauty School. She died as a result of massive head injuries. Many speculated that she and Kempton were killed by the same person.

Nov. 8, 1982. Ronney James Lee, 22, was arrested on an attempted theft charge. Lee’s mother had moved to Portsmouth in 1960, and when Lee got out of the Army in May 1981, he moved in with her. He worked for MBI Security at Liberty Mutual in Portsmouth until August 1982.

July 25-26, 1983. It’s not clear what Lee’s sentence, if any, was for the attempted theft charge, but by the summer 1983, he was back at it. He broke into an apartment on Dennett Street at about 11 p.m. on July 25, and stole a pocketbook, dropping a pack of cigarettes during the break-in. A little more than three hours later, at 2:30 a.m., he broke into an apartment on Austin Street by breaking a window, reaching in, and unlocking it, then crawling in.

In another Lee burglary, it’s not clear when, this one at 22 Weald St., the resident was watching TV in her bedroom at 1:15 a.m., when she noticed the hallway light was off, which was unusual. She went to turn it on and found a man leaning on the light switch. When she asked him what he was doing there, he put a finger to his lips and said “shhh.” She yelled for her sister, and he ran downstairs and out the back door.

Lee was eventually linked to four similar apartment burglaries in the city that year, and a few months later pleaded guilty to the Austin Street one.

Sept. 25, 1985. Little progress had been made in solving either Laura Kempton or Tammy Little’s homicides. Men who had been seen with them, or were friends or acquaintances, were suspects, but investigators couldn’t nail it down.

Portsmouth police Capt. George Krook, in an Associated Press article about unsolved murders in New Hampshire, said they were still actively investigating the two cases.

Assistant Attorney General Brian Tucker said that it could be frustrating for investigators to believe they knew who committed a murder, but weren’t able to prove it.

“You can have a prime suspect, but you have to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt,” Tucker said. “We have to be pretty certain we will win. So a case that appears to be hopeless to the public, may be very close to being solved. The police just lack the one or two pieces of evidence to tie it up.”

This was the same year that Alec Jeffreys, a scientist at the University of Leicester, in England, who’d developed genetic fingerprinting in 1977, was asked to help determine who had raped and killed two girls in the town of Enderby. Jeffreys and his team developed genetic profiling for forensic use, which was used to solve the case in 1986. At the time, though, it wasn’t even a consideration in U.S. crime investigations. In fact, it was more than a decade before it would begin to be used in New Hampshire criminal investigations, and the state didn’t establish its own DNA testing lab until 2003.

Many of the initial suspects in the two Portsmouth homicides remained suspects. None of them were Ronney James Lee.

1987 Ronney Lee was convicted of burglarizing a Keene apartment and sexually assaulting a woman who lived there. She was woken up to Lee touching her at about 3:30 a.m. She screamed, waking up her roommate, and he fled with cash and jewelry. He was later caught. After his conviction, he served time in the state prison from December 1987 to July 1990.

July 10, 1996. The Boston Globe, as part of its “Unsolved Mysteries” series, ran a feature on the Laura Kempton and Tammy Little homicides, in which detectives say a Portsmouth man is, and has been for years, their “number one suspect.” The story, which doesn’t name the man, is picked up by New Hampshire newspapers.

Investigators in the case talk about how they are certain the man did it and they “watch him like a hawk,” and rue the fact there is no physical evidence to tie him to the killings.

By now more than a dozen detectives have worked on the two cases, interviewing more than 200 people, including “friends of the victims, local troublemakers and sailors that were on ships in the port near the time of the killings.”

But, the article says, soon after Little was killed, “they narrowed their search until they arrived at the lone suspect.”

The man was described as a long-time resident of Portsmouth, a manual laborer of “tremendous strength,” who had “a high IQ and minor criminal record.”

While the article didn’t identify the man, he was not Ronney James Lee.

July 2000. Advances in DNA testing prompted the Portsmouth Police Department to submit two samples – the scraping from Kempton’s thigh and the swab from the telephone cord – to Cellmark Diagnostics in Maryland. In August, they got a report back. The lab didn’t get anything from the phone cord, but got a partial male DNA profile from the sperm on the thigh scraping.

2002 Investigators submitted the vaginal swabs and cigarette butt from the Kempton homicide to the Maine State Police Crime Laboratory to be analyzed by forensic DNA analyst Cathy MacMillan. A full male DNA profile was found on one of the vaginal swabs. The cigarette butt reveals a partial profile that matches the other one.

MacMillan also compared the results to the 2000 Cellmark results and found that partial profile also matched. While the results could not conclusively establish that the same person’s DNA was on all three items, it did mean that the man whose sperm was detected on the vaginal swabs could not be excluded as the one who left DNA on the cigarette butt or her thigh.

January 2003. Investigators got a DNA sample from the man who’d been on the date with Laura Kempton the night before she was killed. He was a prime suspect in the case, but the DNA didn’t match.

2003-2016. Investigators at the Portsmouth Police Department upload the DNA profiles to as many databases as they can, including the FBI database CODIS, every crime scene laboratory in the country, and Interpol. CODIS contains DNA profiles contributed by federal, state, and local participating forensic laboratories.

Meanwhile, states began to pass laws that required people arrested for certain criminal offenses to provide a DNA sample. Laws and who is tested vary from state to state, as does who voluntarily submits information to CODIS, so there are still holes in the system in 2023.

Investigators also got comparison DNA samples from anyone who could have potentially been the source of the DNA found at the Kempton crime scene. They eventually eliminate hundreds of people of interest.

December 2016. Portsmouth Police Sgt. John Peracchi hears about an Arizona cold case that was solved using a different type of DNA sequencing, with help from a genealogy company Identifinders International. He contacts Colleen Fitzpatrick at the company to find out if that kind of investigation would help solve Laura Kempton’s case.

He gets the type of DNA sample needed from MacMillan, at the Maine Crime Lab, and it’s determined that the DNA came from a man with African American heritage.

September 2021. Investigators from the Portsmouth Police Department, the NH State Lab and the attorney general’s office met to discuss revisiting forensic genetic genealogy using whole genome sequencing, which had recently developed as an option for suspect identification in cold cases.

May 2022. After the vaginal swab samples from Laura Kempton’s case were submitted to Identifinders International to evaluate if more testing can be done, Det. Erik Widerstrom was notified that there was a profile, and it had been uploaded to a third-party public genetic genealogy database. Three days later, he was told that a relative who had ties to Rockingham County had been identified. From there, the company was able to find the biological parents of the person who’d contributed the DNA, which led to their only son, Ronney James Lee.

Lee had died in 2005, but Widerstrom got a blood card from his autopsy, and McMillan, in Maine, compared it to the DNA profile from the vaginal swabs. It matched.

June 2023. MacMillan directly compared Lee’s DNA profile to the cigarette butt and the thigh scrapings to confirm her earlier findings. She verified that they matched. She also compared his DNA profile to the partial profile that came from the pillowcase in 2003, which also matched. She said that this meant he was a potential DNA donor for those samples.

July 20, 2023. Representatives from the attorney general’s office and the Portsmouth Police Department hold a news conference to announce that the Laura Kempton case is closed and that Lee killed her.

The 25-page report from the AG’s office concludes, “The extremely violent nature of Ms. Kempton’s death and the calculated nature of the break-in to her apartment provide significant evidence that Mr. Lee intended to kill her. However, the evidence, which is circumstantial, is also consistent with a sexually motivated crime that resulted in more violence than the perpetrator originally anticipated. This would be consistent with Mr. Lee’s criminal history. “

The report said, and Formella emphasized, that if Lee were alive today, he’d be charged with first-degree murder.

Tammy Little case still under investigation

While the cold case of Laura Kempton is now closed, the case of Tammy Little, killed on Oct. 19, 1982, and thought to be connected to the Kempton case, remains under investigation, Formella said Thursday.

“It is our hope what we’re announcing today will lead to additional information,” he said, but added that the day was about Laura Kempton and he wasn’t prepared to talk about Little.

Little, 20, like Kempton, was a student at Portsmouth Beauty School at the time of her death.

While there were similarities between the two women that may not have had anything to do with their homicides in 1981 and 1982, there are many that likely do.

Both women lived alone in a ground-floor downtown apartment and were beaten to death during the early morning by an intruder who broke in. It’s not clear if there is forensic evidence in Little’s case similar to that in Kempton’s.