All shook up: Looking back at Maine’s summer of Elvis

Augusta, Maine, owns its Elvis Presley cred, so when the people who run the Augusta Civic Center say that they’re going to try to break the Guinness World Record for most Elvis impersonators in one place, believe them.

AUGUSTA, MAINE – Augusta, Maine, owns its Elvis Presley cred, so when the people who run the Augusta Civic Center say that they’re going to try to break the Guinness World Record for most Elvis impersonators in one place, believe them.

At least 896 Elvis impersonators must show up at the civic center at 6:30 p.m. Wednesday, May 24, to break the record.

“Older Elvis, Younger Elvis, Viva Las Vegas Elvis – get your Elvis on and join us!” says a civic center announcement of the event. The Elvises don’t have to be from Maine. Granite State Elvises are welcome.

“While we applaud Harrah’s Cherokee Casino Resort and their July 2014 World Record of the largest gathering of Elvis impersonators in Cherokee, North Carolina, on July 12, 2014, we can do better than this!” the announcement says.

“Why?’ you may ask.

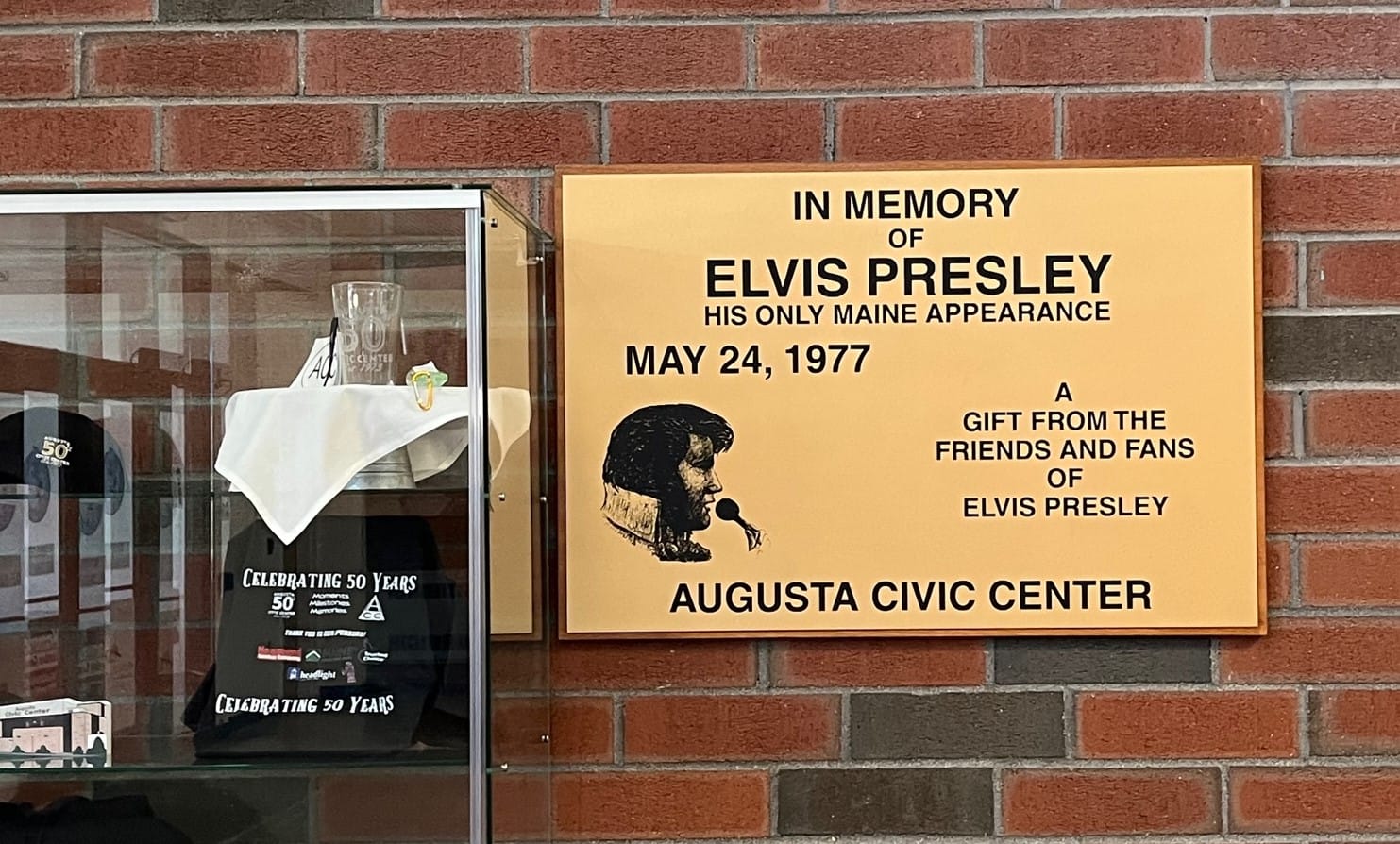

The short answer is that it’s part of the civic center’s year-long 50th-anniversary commemoration. Elvis made his only Maine appearance on May 24, 1977, less than three months before he died.

The long answer is more complicated, tied up in the smaller world of the 1970s, but also in the perseverance of a little city whose big wins still go largely unnoticed.

But for six months n 1977, Elvis fever gripped Maine – and northern New England – in a way no entertainment-based event has before or since. And the Augusta Civic Center was at the center of it.

Don’t Be Cruel

Lionel Dubay, the civic center’s director in 1977, had been trying to get Elvis to perform there since it had opened four years before. The odds weren’t great – it seated 7,000, much smaller than the venues Presley usually played. And, of course, Augusta, population 18,000, isn’t exactly on the beaten track.

Still, Dubay was used to the civic center exceeding expectations since it had opened four years before in the north end of the city, an area that was mostly woods and farmland.

The Capitol Board of Trade, a group of area businessmen, had faith that an indoor arena and convention center would be an economic boon. There were no similar venues in central Maine, and Interstate 95 had been extended to the city just a few years before. They bought several acres of farmland and deeded it to the city for one dollar.

The $3 million civic center opened Jan. 6, 1973. From the start, it hosted concerts, trade shows and high school basketball tournaments. It quickly proved it wasn’t the boondoggle some had predicted. It started running in the black its second year and never looked back.

By late 1976, the civic center had hosted musical acts including Aerosmith, the J. Geils Band, Bob Dylan and the Rolling Thunder Review (my first-ever concert) and many popular country acts like Freddy Fender, Buck Owens and the Statler Brothers. Johnny Cash had visited three times by the end of 1976.

An Elvis concert, though, would “put Augusta on the map,” Dubay said.

He’d been writing letters and making phone calls to Elvis’ management company, Concerts West, for three years, even offering to foot the cost of the flight. Concerts West wasn’t interested.

But as Elvis launched his 1977 tour, Dubay got a yes.

Elvis, 42, suffered from hypertension, chronic pain and a myriad of ailments. His handlers kept him going with a cornucopia of prescription drugs. Presley was overweight and had become the butt of jokes by then. What wasn’t as public was his serious work ethic. Dozens of employees relied on him showing up every night. He’d tell people no matter how he felt he “had a payroll to meet.” In 1976, he’d played 100 concerts, drawing more than a million fans.

Concerts West, assured by Dubay the show would sell out, jammed the performance in between a May 23 appearance in Providence, Rhode Island, and a May 25 show in Rochester, New York. At the time, the Rhode Island show and one in August in Hartford, Connecticut, were the only other New England performances scheduled in Presley’s 65-city tour.

There was no fanfare when the news was announced. A small article on the entertainment page of the Kennebec Journal, Augusta’s newspaper, on Saturday, March 26, said tickets would go on sale that Tuesday. The Associated Press picked it up, and a few paragraphs ran in newspapers and on radio stations throughout the region.

Dubay was likely the only one who realized what would happen next.

In an unprecedented move, he said the civic center would not take phone or mail orders for tickets, they had to be picked up at the box office. And buyers would be limited to six apiece.

“It’s going to be a pleasure to host the biggest name in the business,” he said.

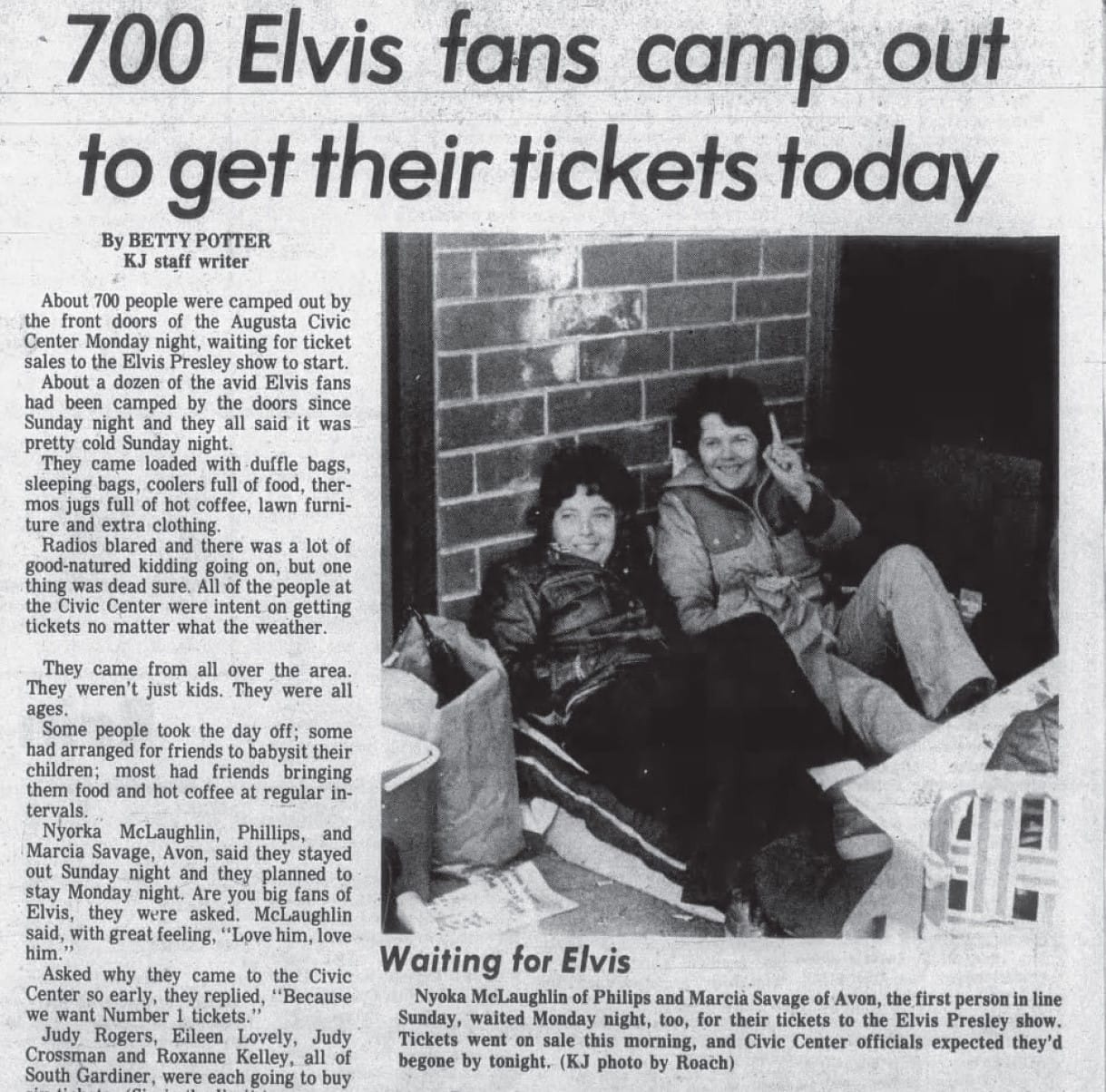

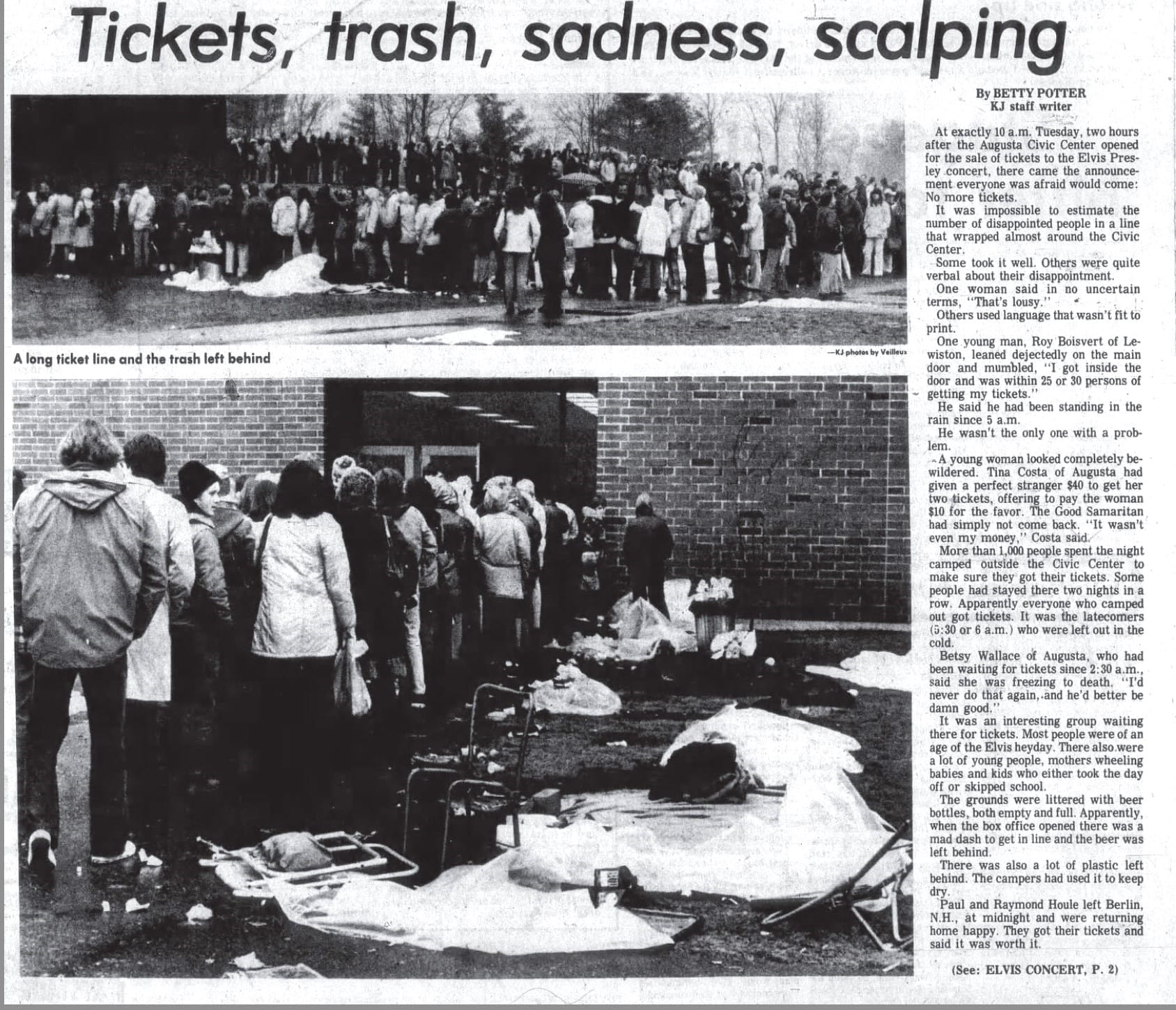

Sure enough, fans started lining up outside the civic center on Sunday night. By Monday night, a reporter counted more than 700 people waiting. The crowd endured an overnight rainstorm Monday, never fun in March in central Maine, but that didn’t stop people from coming. One Portland newspaper estimated by Tuesday morning there were more than 5,000 people in line. They included Paul and Raymond Houle, of Berlin, New Hampshire, who told a reporter they’d left home at midnight to get in line.

When a second line formed in front of a door farther along the building Tuesday morning, some fans “became irate,” according to news reports.

A woman from Atlantic City, New Jersey, griped to a reporter that she had “driven all night to the middle of nowhere” to get tickets, enduring the rain and cold. Now, “The management of this building has denied us our pursuit of freedom to see Elvis from the first row.”

She added, “It just shows you how rotten things have gotten in this country.”

Other articles, though, stressed the friendly atmosphere, with fans swapping stories, food and sheets of plastic to keep the rain off.

Tickets sold out in two hours, a box office record until online ticket selling was introduced years later.

Suspicious Minds

A Kennebec Journal headline the next day summed up the aftermath: “Tickets, trash, sadness, scalping.”

One major theme in letters to the editor was the fact that people from out of state got tickets when people from Maine were left empty-handed.

“I understand that three-quarters of the tickets sold went to out-of-staters,” one letter in the Lewiston Sun steamed, though it didn’t cite sources. “I feel that in the future if a great performer such as Elvis Presley comes to Maine, that some sort of identification should be used to provide Maine residents with the first opportunity to purchase their tickets.”

A letter in the Kennebec Journal said that Augusta residents, “whose taxes support the civic center,” and others who support the arena year-round “should have had preference over the out-of-staters and Canadians who it seems knew it before Augusta folks did and it seemed were camped out two or three days before ticket sale day.”

In true newspaper fashion, no one pointed out that civic center revenues actually supported Augusta, not the other way around. Or that It’s likely in those pre-internet days that the “out-of-staters and Canadians” found out about the concert the same way the locals did, through AP stories in their local newspaper and on the radio.

Another controversy erupted when news leaked that tickets were put aside for city officials and civic center employees, a practice that had been in place since it had opened. They still had to pay for them, but that didn’t matter to people who didn’t get tickets.

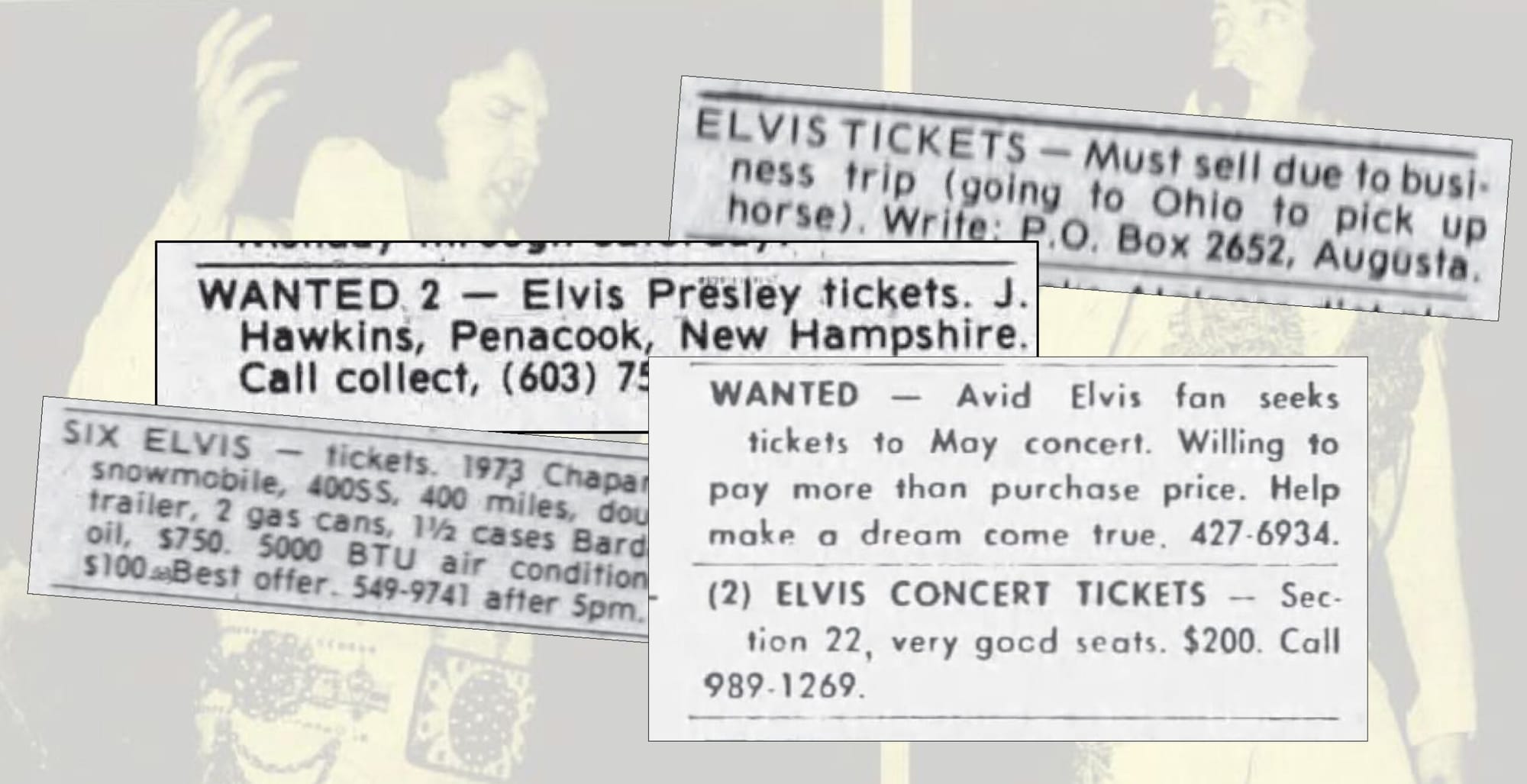

By April 1, newspapers reported that scalpers were selling the $12.50 and $15 tickets for as much as $100. Scalpers became the new target of letter-writer, radio DJ and man-on-the-street newspaper article vitriol.

Meanwhile, newspaper classified ad pages filled with desperate fans looking for tickets.

“Wanted 2 Elvis Presley tickets. J. Hawkins, Penacook, New Hampshire. Call collect,” said one ad.

Another ad by an “avid Elvis fan” promised to pay more than the purchase price for tickets. “Help make a dream come true.”

Sellers, too, bought ads. One said, “Must sell due to business trip (going to Ohio to pick up a horse).”

Two fans suggested that Elvis address the Maine State Legislature. “That’s an absolutely stupid idea,” House Speaker John Martin told a reporter. Case closed.

Snark from newspapers in Maine’s two biggest cities, Portland and Bangor, where there was a natural inclination to dismiss or demean anything related to Augusta, was on full display.

Bangor Daily News outdoor columnist Bud Leavitt mused that maybe Augusta would “at least wash down its streets for Elvis’ night on the town.”

A Portland newspaper columnist talked to a Cumberland County Civic Center official who said that the issues that happened outside the Augusta Civic Center wouldn’t happen at the Portland arena, which had just opened that year.

There were also feel-good stories. Superfan Dick Edwards, of Mechanic Falls, had two extra tickets and gave them away to the fans who wrote him the best letters about why they should get them.

A woman who’d given a stranger in line $40 to buy two tickets, then couldn’t find her, told a reporter about it. After an article appeared, the woman with the $40 contacted the paper, saying she didn’t get tickets before they sold out, then couldn’t find the woman to give her money back. A reunion was engineered and everyone was happy. Or as happy as they could be without tickets.

There was a scare in April when Elvis got sick and had to cancel four shows. But it was followed by relief when it was announced the Augusta May 24 show would not be affected.

Every single day between the ticket sales and the concert, at least one of Maine’s daily newspapers had an article related to Elvis.

With that kind of hype, what could go wrong?

Love Me Tender

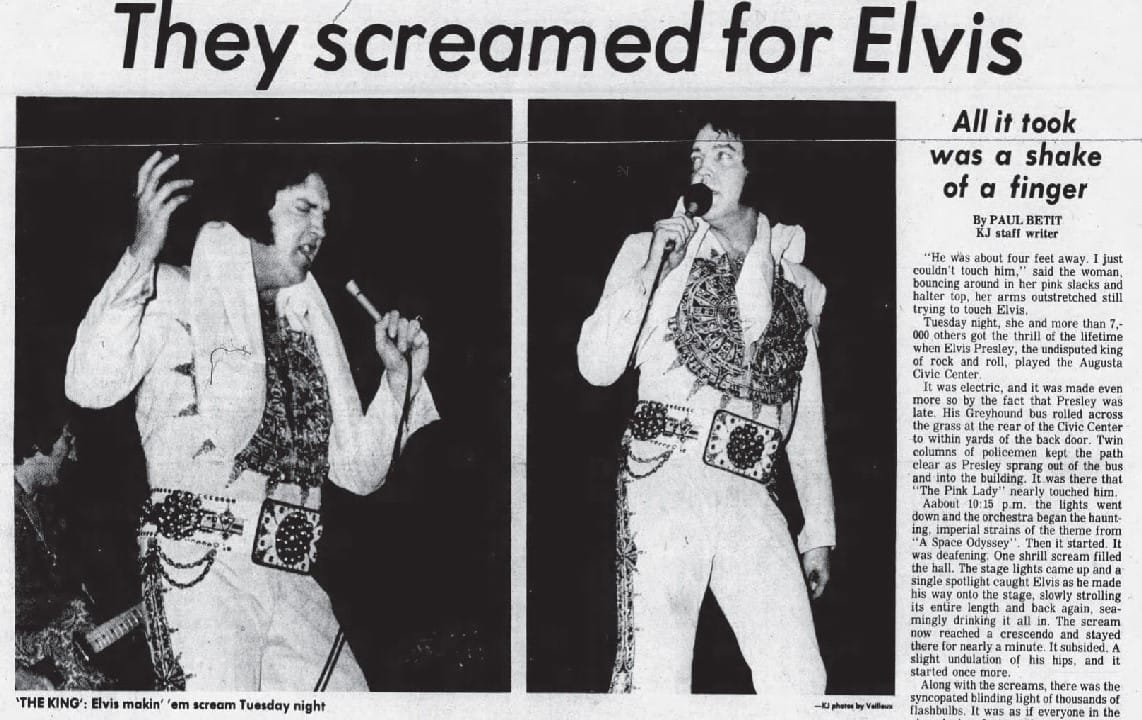

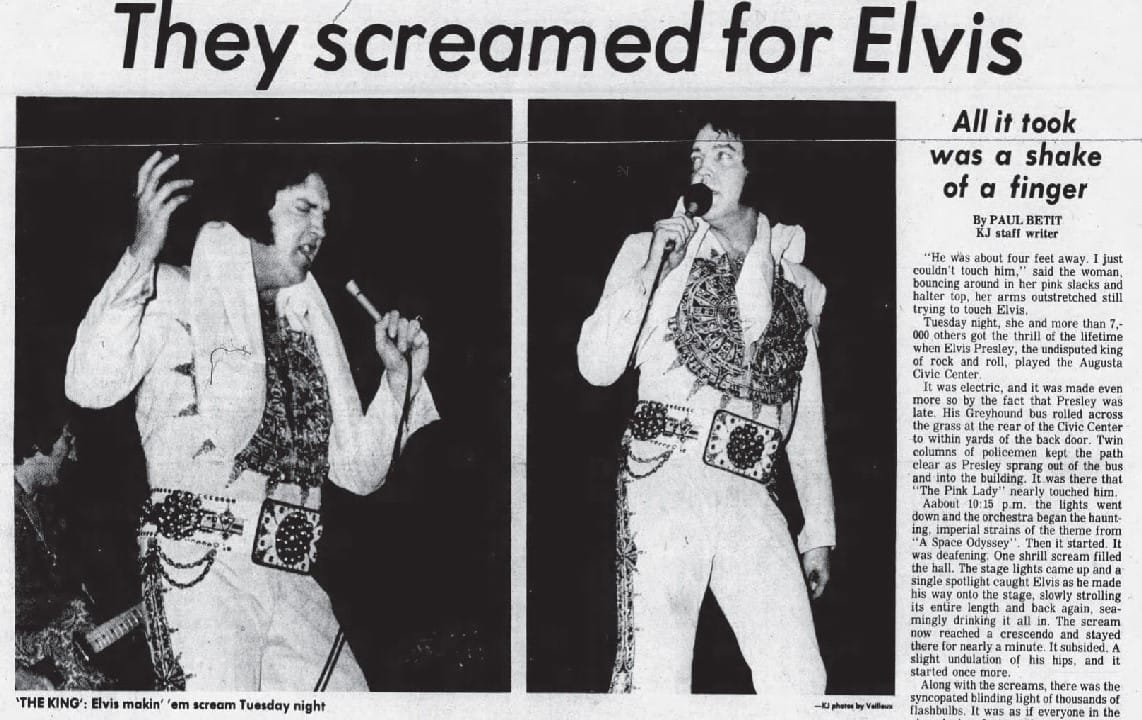

The show began at 8:30 p.m. with warmup acts Joe Guercio and the Hot Hilton Horns, Canadian comedian Jackie Culhane and a third act, Gospel trio Sweet Inspiration. Still, fans had to endure a 45-minute intermission after the acts before Elvis arrived.

Newspapers columnists and reporters chalked it up to Presley being a prima donna. Apparently no one asked what happened. It turned out the bus ferrying him from the Portland airport, an hour to the south, was delayed.

Elvis was anything but a prima donna, Dubay later recalled. “For all that he was a superstar, he had the simplest rider requirements of almost anyone in the business,” he said in a 1987 article. All Presley asked for was a pitcher of ice water, six towels and a full-length mirror. When the bus arrived at the civic center, Presley didn’t go to his dressing room, he headed right for the stage.

Diane Gagnon, events coordinator at the civic center, said that despite the wait, when Presley came on stage to the strains of the theme for “2001: A Space Odyssey” the crowd was all his.

“There were spotlights going on and off and cameras flashing all over the place,” she said in the 1987 article. “We had to wait a long time for people to stop clapping. It was indescribable. People were saying, ‘My God, is it really him?’”

Dubay said when Presley was done, civic center officials hustled him back out to the bus, so it wouldn’t get stuck in parking lot traffic.

Two of the state’s newspapers covered the concert, and both focused on Presley’s “paunch,” how much he sweated, and how crazy the fans acted.

The Bangor Daily News sent a young reporter, admittedly not an Elvis fan, who wrote a first-person piece about her impressions of fans with the unfortunate headline, “Elvis fans: a show in themselves.”

Outraged fans (and subscribers) deluged the paper with letters.

The editor incomprehensibly doubled down, violating the sacred newspaper rule “You don’t [poop] where you eat.” His editorial managed to be misogynist, age-shame and fat-shame in eight short paragraphs.

The editorial referenced the fact that the “mostly female” audience was upset that Elvis had gained weight (it’s not clear where this came from, since neither the reporter’s story nor review mentioned fans being upset with Presley’s weight). “There’s nothing sadder than a rock star with a spare tire,” he wrote. “Especially if you’re a girl well past 30 intent on recapturing magic moments.”

The editorial concludes that Presley likely left so abruptly because he “may have taken one look at the Augusta over-30 set and decided that all the spring chickens had gone south, and to heck with the encore.”

That, of course, spurred a new deluge of letters, all of them blaming the reporter, by name, for things the editorial had said.

The Augusta City Council, after Elvis played, agreed the civic center should pursue as many rock concerts as possible.

One city councilor wasn’t convinced, though, and attended a Bad Company/Climax Blues Band show to see what all the fuss was about. Afterward, he declared that the concerts were contributing to the delinquency of Augusta’s youth and said the city council should limit them to, at the most, one a year.

That brought major pushback from business owners near the civic center, who said they doubled or tripled their take when there was a rock concert.

The manager of the nearby Howard Johnson’s said the Elvis concert had given him the most business he’d ever had. He added he’d had no spike in business when comedian Bob Hope performed.

Also benefitting from Elvis fever were Elvis impersonators, several of whom were profiled in the state’s newspapers as spring became summer. None was bigger than Larry Seth, the Big El, promoted as “more Elvis than Elvis himself,” who signed on for a long-running gig at The Portlander Hotel in Portland, and played to about 2,000 fans at that city’s Cumberland County Civic Center two weeks after real Elvis was in Augusta.

Can’t Help Falling in Love

The biggest Elvis news of the summer when it was announced came in late July when he’d play Aug. 18 at the Cumberland County Civic Center, in Portland.

The announcement was made on a Wednesday, two days before tickets went on sale. Fans immediately began lining up at the 9,200-seat downtown Portland arena for the $10 and $15 tickets.

Superfan Wayne Campobasso, of Saco, “who’d once (unsuccessfully) paid $600 to shake Elvis’ hand,” was one of the first in line, the Evening Express reported. He would continue to be fodder for Elvis-related news stories for months to come.

Presley had a break built in between his June 26 show in Indianapolis and Aug. 19 show in Utica, New York, so Concerts West tacked the Aug. 18 show on in front of Utica.

That break came in handy when the Aug. 18 show sold out the morning tickets went on sale. A second show, for Aug. 17, was added, with tickets going on sale immediately.

Both shows sold out, spurring a fresh onslaught of letters to the editor griping about the same things people had griped about after the Augusta Civic Center tickets sold out. Scalpers! Out-of-staters! Civic center management messing up people’s lifelong dream!

But Maine’s Elvis fans were also more prepared this time.

One enterprising Portland auto dealer promised two free tickets as “his guest” at the show with purchase of a Toyota.

Campobasso, the guy who was first in line, scored front-row seats for himself and his wife for both nights. Campobasso told the Biddeford Journal-Tribune that he’d had a portrait of Elvis and his daughter, Lisa Marie, commissioned and planned to present it to Presley backstage.

Superfan Dick Edwards, who’d given away two tickets for the Augusta show to letter writers, gifted one for the Portland show to Cindy James, 16, of Gardiner. He told several newspapers he was now looking for someone to drive her to Portland, as well as a restaurant to comp her dinner to give her “a night to remember.”

Edwards had formed the Elvis Presley True Fan Club of Maine shortly after the Augusta show, and said it already had 200 members.

In Waterville, 20 miles north of Augusta, Michaud Jewelers fashioned a pin for Elvis: a solid gold scarf studded with Maine tourmaline and five diamonds, worth about $1,000. Jeweler George Holmes planned to present it to Elvis backstage.

By Aug. 15, Col. Tom Parker, Presley’s manager, and other members of his crew, were already at the South Portland Sheraton. Elvis was still in Memphis, planning to fly to Portland the next day in his private plane, the Lisa Marie.

On the afternoon of Aug. 16, Mary Goulding, Cumberland County Civic Center receptionist, waited for Parker and others to arrive to prepare for the next night’s show.

“We waited all afternoon,” she recalled in 1987. “We waited and waited. When nothing happened by five o’clock, I left.”

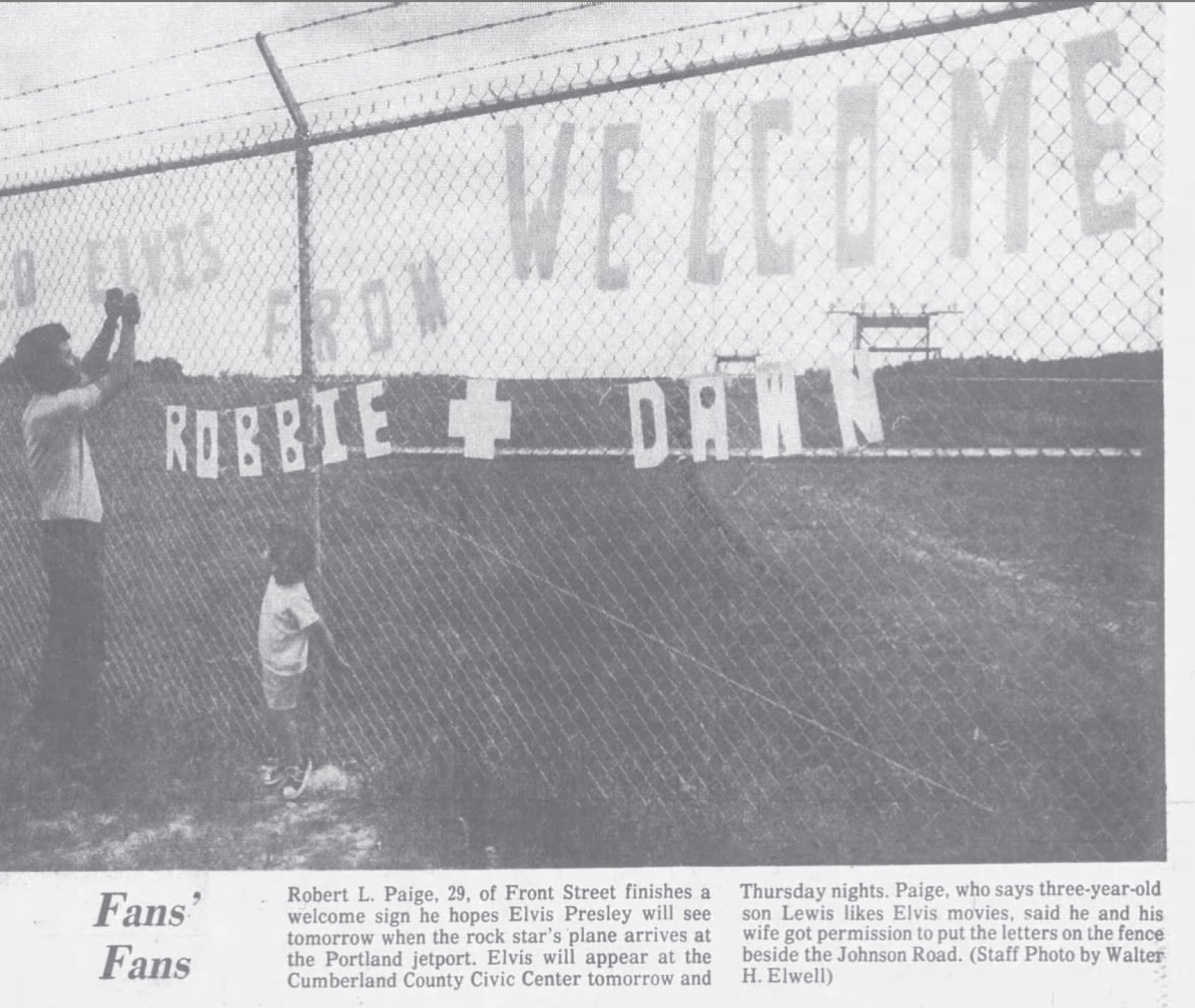

That morning, superfan Robert Paige, of Portland, was photographed with his 3-year-old son, Lewis, hanging a welcome sign for Elvis on the fence that surrounds the Portland airport. The photo appeared that afternoon in the Evening Express.

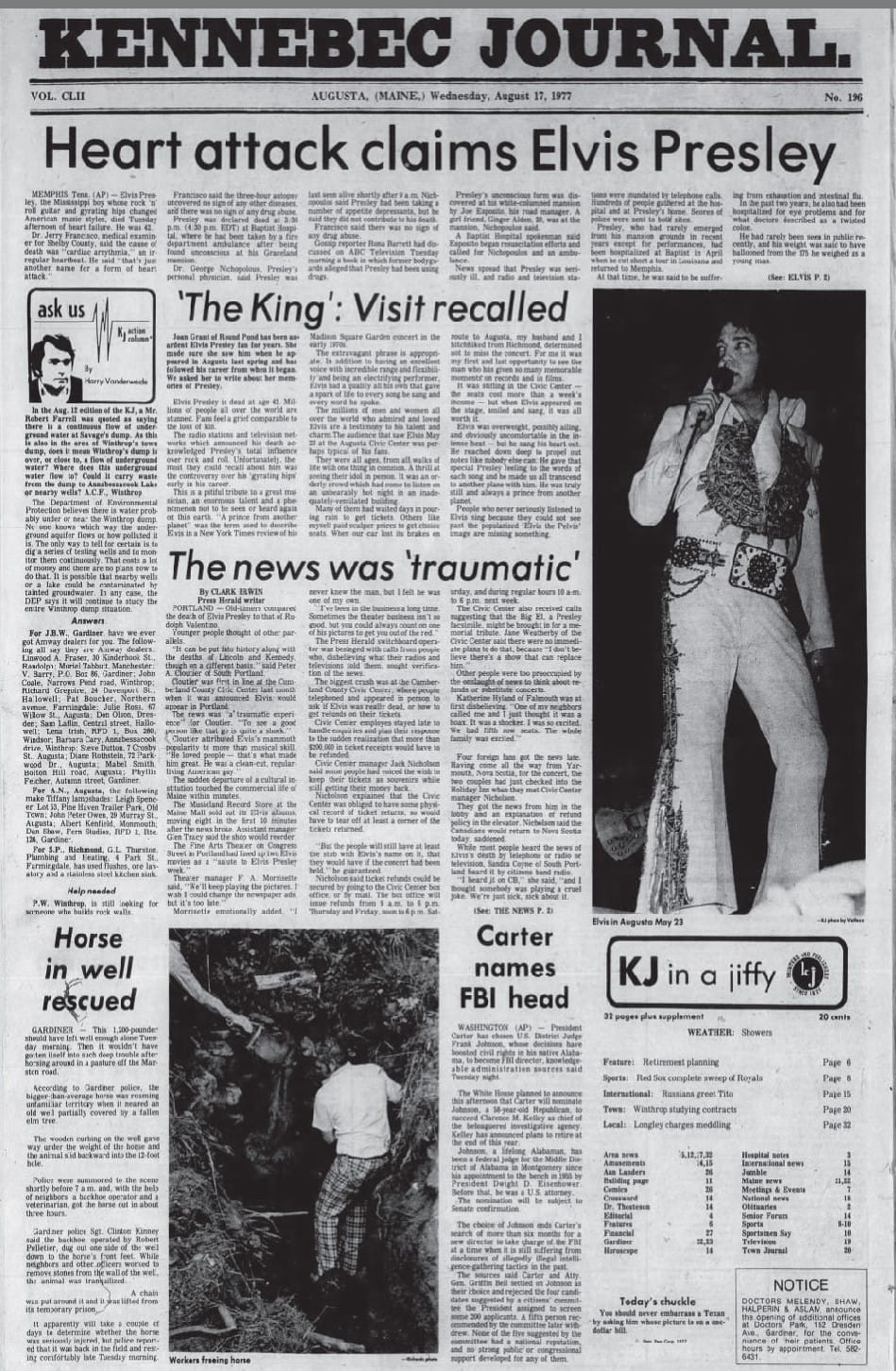

By the time the paper came off the presses, Elvis was dead.

Elvis Has Left the Building

Elvis fever had run high in Maine ever since the unexpected (except by Lionel Dubay) onslaught of fans to buy tickets in March. It had spiked as the two shows in Portland drew near, pulling everyone into its vortex, whether fans or not. In newspapers, on the radio, on the TV news, it was Elvis in Maine, 24/7.

News of his death sucked all the air from the state.

Newspaper and radio station switchboards were besieged with calls from fans asking if it was true. One radio station reported their switchboards shutting down (the 1977 version of crashing a website) from all the calls.

Fans lit up the phones at the Cumberland County Civic Center, but even more showed up, many sobbing, trying to grasp how it could all change so suddenly.

The night of Aug. 16, civic center employees stayed late “to plan their response to the sudden realization that more than $200,000 in ticket receipts would have to be refunded,” the Press Herald reported.

Something had to fill the vacuum.

Elvis impersonators, who’d already had a big bump in business after the Augusta show, were now in such demand they had to turn some jobs down. Larry Seth, The Big El, was the hottest, and a favorite of the dozens of tribute shows that popped up at hotel lounges, bars and country fairs across the state.

Some of the tributes were hosted by the Elvis Presley True Fans of Maine, who were raising money for a bronze bust of Presley to be installed in the Cumberland County Civic Center.

The group commissioned artist Ed Materson to sculpt it, and it was expected to be completed by November. Unfortunately, no one checked with the civic center board of directors, who, in November, agreed the bust “wouldn’t be appropriate” for the arena’s image.

Up in Augusta, though, they embraced their Elvis cred.

When the Elvis fans proposed a plaque for the Augusta Civic Center to commemorate Presley’s only Maine appearance, Dubay thought it was a great idea. So did the city council.

The Elvis Presley True Fans of Maine raised the money for the $800 plaque, which Augusta city officials said had to fit in with the other memorial plaque in the lobby.

The Elvis bust that had been rejected in Portland traveled around Maine for a few years, appearing at the Maine Mall, fan shows and the like before fading into obscurity.

Augusta Civic Center has proudly displayed its commemoration of Elvis’s show in its lobby for more than 40 years.

The Augusta show grossed $107,000, and $92,000 of that went to Presley’s promoter.

“That was all right,” Dubay said. “It did a lot for Augusta. It filled the motels and restaurants. People came from all over the state.”

The show was a milestone for the civic center, he said. “We were hosting a superstar. A legend in his own time. I’ll never forget it.”